The people of London who had managed to survive the Great Plague in 1665 must have thought that the year 1666 could only be better, and couldn’t possibly be worse!

Poor souls… they could not have imagined the new disaster that was to befall them in 1666.

A fire started on September 2nd in the King’s bakery in Pudding Lane near London Bridge. Fires were quite a common occurrence in those days and were soon quelled. Indeed, when the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Thomas Bloodworth was woken up to be told about the fire, he replied “Pish! A woman might piss it out!”. However that summer had been very hot and there had been no rain for weeks, so consequently the wooden houses and buildings were tinder dry.

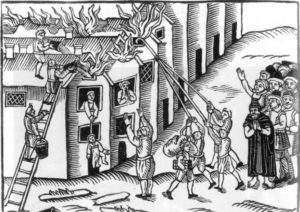

The fire soon took hold: 300 houses quickly collapsed and the strong east wind spread the flames further, jumping from house to house. The fire swept through the warren of streets lined with houses, the upper stories of which almost touched across the narrow winding lanes. Efforts to bring the fire under control by using buckets quickly failed. Panic began to spread through the city.

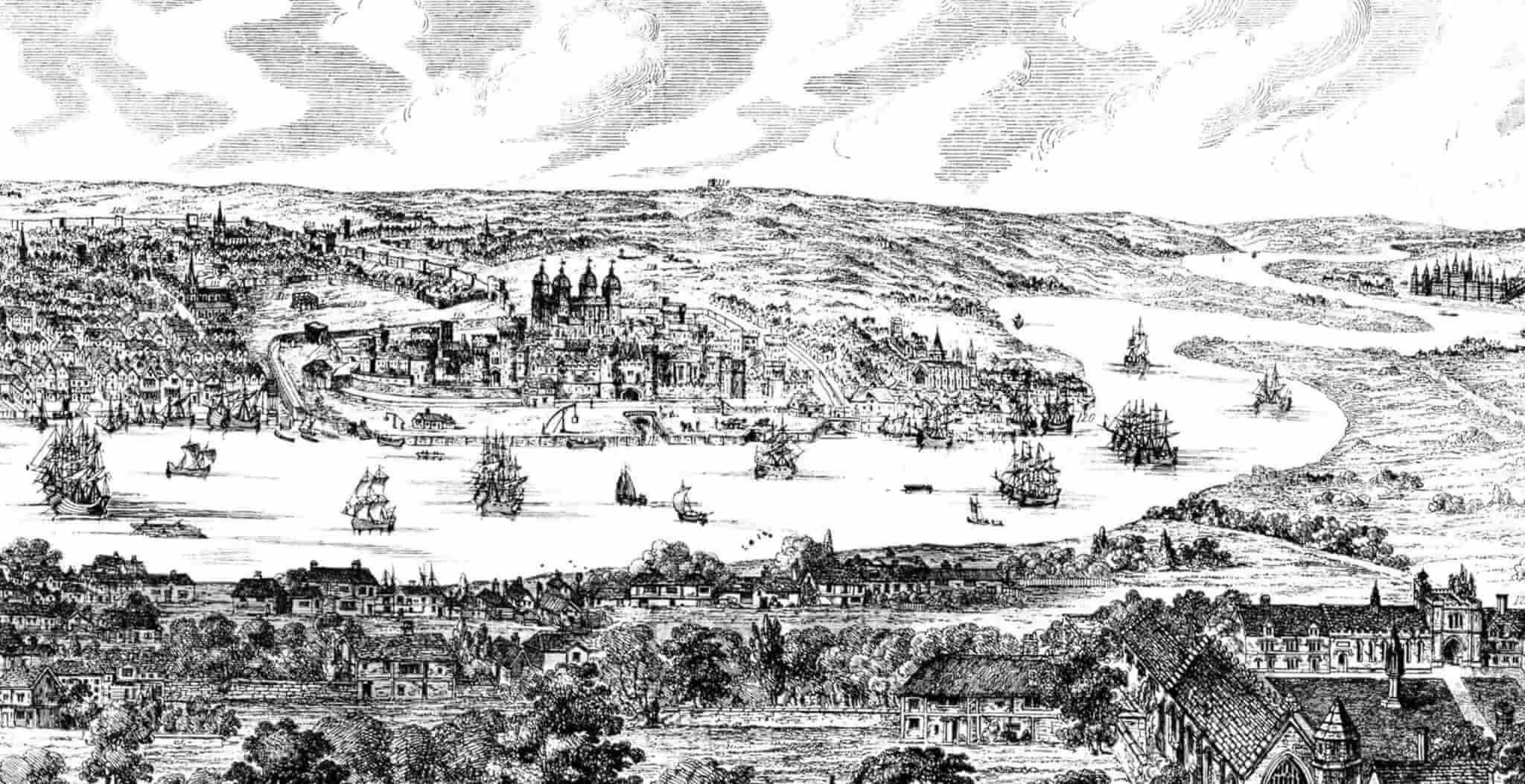

As the fire raged on, people tried to leave the city and poured down to the River Thames in an attempt to escape by boat.

Absolute chaos reigned, as often happens today, as thousands of ‘sightseers’ from the villages came to view the disaster. Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, the diarists, both gave dramatic, first-hand accounts of the next few days. Samuel Pepys, who was a clerk of the Privy Seal, hurried off to inform King Charles II. The King immediately ordered that all the houses in the path of the fire should be pulled down to create a ‘fire-break’. This was done with hooked poles, but to no avail as the fire outstripped them!

Absolute chaos reigned, as often happens today, as thousands of ‘sightseers’ from the villages came to view the disaster. Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, the diarists, both gave dramatic, first-hand accounts of the next few days. Samuel Pepys, who was a clerk of the Privy Seal, hurried off to inform King Charles II. The King immediately ordered that all the houses in the path of the fire should be pulled down to create a ‘fire-break’. This was done with hooked poles, but to no avail as the fire outstripped them!

By the 4th September half of London was in flames. The King himself joined the fire fighters, passing buckets of water to them in an attempt to quell the flames, but the fire raged on.

As a last resort gunpowder was used to blow up houses that lay in the path of the fire, and so create an even bigger fire-break, but the sound of the explosions started rumours that a French invasion was taking place… even more panic!!

As refugees poured out of the city, St. Paul’s Cathedral was caught in the flames. The acres of lead on the roof melted and poured down on to the street like a river, and the great cathedral collapsed. Luckily the Tower of London escaped the inferno, and eventually the fire was brought under control, and by the 6th September had been extinguished altogether.

Only one fifth of London was left standing! Virtually all the civic buildings had been destroyed as well as 13,000 private dwellings, but amazingly only six people had died.

Hundreds of thousands of people were left homeless. Eighty-nine parish churches, the Guildhall, numerous other public buildings, jails, markets and fifty-seven halls were now just burnt-out shells. The loss of property was estimated at £5 to £7 million. King Charles gave the fire fighters a generous purse of 100 guineas to share between them. Not for the last time would a nation honour its brave fire fighters.

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, a poor demented French watchmaker called (Lucky) Hubert, confessed to starting the fire deliberately: justice was swift and he was rapidly hanged. It was sometime later however that it was realised that he couldn’t have started it, as he was not in England at the time!

Although the Great Fire was a catastrophe, it did cleanse the city. The overcrowded and disease ridden streets were destroyed and a new London emerged. A monument was erected in Pudding Lane on the spot where the fire began and can be seen today, where it is a reminder of those terrible days in September 1666.

Sir Christopher Wren was given the task of re-building London, and his masterpiece St. Paul’s Cathedral was started in 1675 and completed in 1711. In memory of Sir Christopher there is an inscription in the Cathedral, which reads, “Si Monumentum Requiris Circumspice”. – “If you seek his monument, look round”.

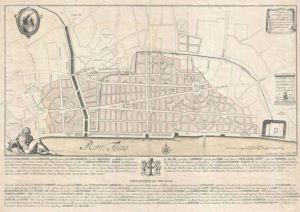

Wren also rebuilt 52 of the City churches, and his work turned the City of London into the city we recognise today. The above map, said to be a reproduction of the original, shows Sir Christopher Wren’s plan for reconstructing the city following the Great Fire of London. Note on the lower left-hand side an image of Thamesis, the river god after whom the River Thames is named. In the upper left-hand side the mythical phoenix suggests that London too would rise from the ashes.

Some buildings did survive the conflagration, but only a handful can still be seen to this day. For details and photos, please see our article, ‘Buildings that Survived the Great Fire of London’.

Published: 1st July 2020