In Memory of Harry & HMS Glorious

In memory of Corporal Ralph Henry Neale 542013 RAF, died 10 June 1040 age 26yrs.

Corporal Ralph Henry Neale

My father wakes in the night, ‘Harry, Harry,’ he calls urgently shaking my mother’s arm. Startled awake, she mutters, ‘What is it?’

‘Harry, wake up, we must get going,’ Dad says urgently.

‘I’m not Harry,’ Mum replies.

Dad is 100 years old, and Harry, who drowned in the frigid arctic waters of the North Sea when the HMS Glorious was torpedoed, would be 102. Of his bones are coral made, or long since disintegrated. For Dad, Harry is always 26 and he, the younger brother Bob, watching, admiring. They shall not grow old as we who are left grow old.

Ralph Henry, named for his father and grandfather, always called Harry. A jaunty young man; photographed in 1940, RAF cap slightly awry, grinning, ready for adventure. Proudly serving on the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious, whose end was unnecessary and so inglorious.

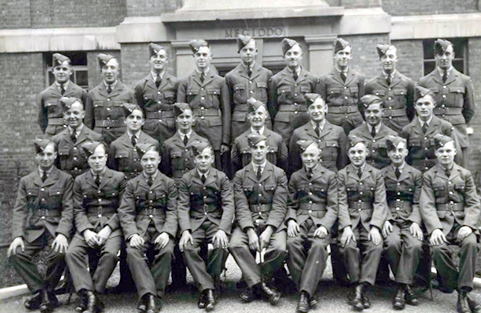

Harry, second front row left, with Squad 46 Struma

Bob and Harry, two country brothers, roaming the Gloucestershire fields and hills, eyeing the girls, working side by side, enjoying a game of darts and a drink. Eager to be active, earn a bob, make something of their lives. Didn’t need to enlist. Could have stayed working on the farm, a reserved occupation, but they hear the call and are keen to do their bit. The Royal Air Force lures them both.

Maybe Harry, the elder, goes first, then Bob follows. We don’t know.

We don’t know, either, how soon the news reached the Cheltenham countryside that Harry was missing. Probably a telegram, missing in action, believed dead, arrives as freezing men clung to the debris of the Glorious, or shivered in ill prepared lifeboats.

Harry’s mother, Mabel is 45. She married young, had her eldest at 19. Harry is her second child, her first son. She sees the grim face of the telegram boy and knows before she reads. She grows pale, thanks the telegram boy, it’s not his fault, stares at the piece of paper thrust into her hand. She gropes her way to the nearest seat, sinks down, legs shaking.

The telegram does not tell the full story. Thank god for that. Harry’s mother and all the families may never learn exactly what happened to the Glorious and her crew; those awful details are hidden for decades. Many men died. A fact of war, a tragedy – and the truth covered up.

Eight decades ago, the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious, originally built in 1916 as light battle cruiser, was returning to the Fleet base at Scapa Flow. Instead she sank to the ocean’s depths. 900 men went down with her including Harry, the brother Bob calls for in the night.

HMS Glorious

HMS Glorious

For three days the men of the Glorious endured, huddling in ill prepared lifeboats, others clinging to its sides in the icy water, some desperately clutching pieces of detritus. No shelter. No hope.

‘Chin up boys,’ one man said. ‘They’ll be here. Within 8 hours. The manuals say that. Remember.’

‘Keep going lads’, another called. ‘It won’t be long. They’ll find us.’

They never did. Not in time to save them all. One by one the arms, and the spirits, of the exhausted men grow weak – they let go, first raising a hand, it was said, as if asking permission to go, bidding farewell. Ceased clinging, sank quickly. Bubbles and froth signaled their going. Then, nothing.

A Norwegian boat picks up the few survivors. Many don’t make it to the shores of Norway. They lie in the cemetery of Torshavn, on Faroe Island. 38 men are eventually taken to Aberdeen hospital. It takes them 10 months to fully recover.

According to the enquiry, HMS Glorious asked to leave the safety of the convoy due to low reserves of fuel. She only had her escorts HMS Ardent and HMS Acasta for protection. No spotter planes to shield her, no-one in the crow’s nest; bereft of any signals to warn her of circling German boats.

The code encryptors at Bletchley Park are well aware of the danger. They decipher a signal and inform those above them, assuming they will ensure the Glorious is warned. That signal never gets through.

Glorious, Ardent and Acasta are all sunk by the destroyers, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau; filming as their torpedoes flew. ‘A good day’s work,’ their crew said afterwards. Not stopping for the men floundering in the icy water; it was war.

German battleship Scharnhorst firing on the British aircraft carrier Glorious and her escorts, 8 June 1940.

German battleship Scharnhorst firing on the British aircraft carrier Glorious and her escorts, 8 June 1940.

Nearby in the sub-zero ocean was HMS Devonshire; she picks up the distress signal but cannot go to the rescue of the Glorious and her drowning crew. She carries a precious cargo; King Haakon of Norway – and instructions from Churchill himself. Guard the king at all costs, no wireless contact, nothing must give away your position. 900 men are drowning, yet Devonshire’s captain must ignore that signal. Her signalmen see it. 60 years later they recall the horror of knowing nearby the lives of Glorious’ crew are ebbing away.

At the enquiry, evidence was given, explanations were forthcoming; much of it still rejected by Naval historians. Since then further crucial evidence has emerged.

Mabel and the families who waited so many years ago, hoping the words presumed dead were wrong, never learned these details. Far better that they never heard of the men floundering in glacial waters, waiting and wondering why help never came.

The naval crew, airmen and officers of the Glorious, Ardent and Acasta are gone. By now, the few survivors as well. Also gone, are the captains, commodores, politicians of the day, who played a part in the tragedy.

Harry’s mother is long dead, his father and brother Bob too. Bob would be 107. So often he waited and called for Harry, ‘Harry’s late, where is he? Do you know where Harry is, my dear.’

‘I expect he’s still at work, Dad,’ I say, ‘He’ll be here soon.’

‘Do you really think so?’

‘Yes, I’m sure.’

On Remembrance Day each year, at the 11th hour, of the 11th day, on the 11th month, we honour those killed in the Great War, WWII, Korea, Iraq, Afghanistan and all the wars. Bugles sound the Last Post as we stand proud, our poppies pinned in place. And I recall Harry and the crew of HMS Glorious, now embraced by centuries of sandy grains, as sea creatures scuttle past and ocean fronds brush their bones.

Lesley Neale (l.neale@curtin.edu.au) was born in London. She is a freelance writer, researcher/tutor at Curtin University, Western Australia; currently living in Perth near a nature reserve full of Banjo frogs. She has one son and four sisters. Life-long interests are British social history, biography, politics, drawing, travelling and coffee with friends

Published 25th October 2022