Bouts of childhood illness in our house were improved by one sparkling remedy: Lucozade! Inspired by fellow HUK author Terry MacEwen’s article on IRN-BRU (made in Scotland from girders!), turning the focus on Tyneside’s own fizzy and lurid-coloured restorative seemed a suitable rejoinder.

There was a ritual to drinking Lucozade in the old days. It came wrapped in crinkly cellophane of a rather jaundiced yellowish hue. The liquid contained in the glass bottle was yellow-orange as well. I think the intention was to invoke a sense of sunny glowing health in the invalid. However, in retrospect it was perhaps not the best option for anyone suffering a bilious attack.

After the removal of the crackling outer wrapping came “the opening of the bottle”. The bottle was a bit different too, as it wasn’t smooth, but had bumps on the tapered neck. With a fizz and a glug, the sparkling, sugary tonic was poured into a glass and the sufferer urged to drink it all up. In those far-off days, sugar was not demonised, but rather viewed as essential to providing the energy to get sick people back on their feet again, especially if they couldn’t face solid food.

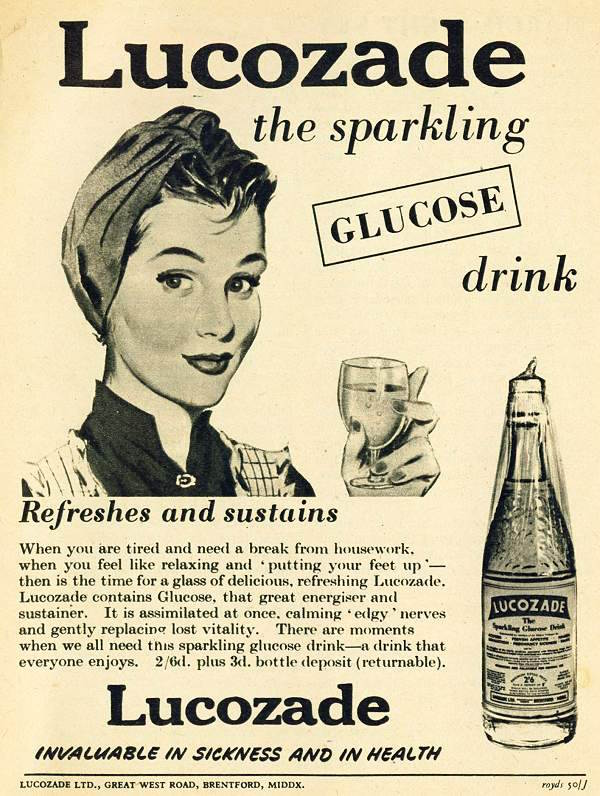

Not sugar, but glucose. That was the quasi-scientific description of what made Lucozade a fizzy drink like no other. That’s the clue to what appears to have been its first commercial name, too: Glucozade.

One dictionary definition of glucose is: 1. “a white crystalline sugar, the most abundant form being dextrose. Formula C6H1206. 2. a yellowish syrup obtained by incomplete hydrolysis of starch: used in confectionary, fermentation etc.” Glucose derives from the Greek for sweet, and perfectly describes the qualities of this thick, sweet, gluey drink that cheers but not inebriates. Sugarade would never have cut it.

Like many brands that are now global names, the history of Lucozade is complex, and several names have been cited as the inventors of the drink. However, Newcastle University credits Professor Pybus (which sounds like the perfect name for a professor on a quest to a lost plateau with dinosaurs) as the real creator of the reviving glucose drink.

Professor Pybus was a surgeon at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle. He realised that children who were literally starved at the time of emergency operations, were at risk from serious illness or death. Indeed, it was the tragic death from of one young child with the symptoms of cyanosis that convinced Pybus that some kind of drink that was easily digestible and energy-giving, should be given to them up to the time of their operation. The drink they developed was based on glucose. Soon many hospitals and nursing homes in the North East were using the formula, which was then commercially produced by a chemist in Barras Bridge, Newcastle. It was selling for 2 shillings and sixpence a pint (2/6d), and according to some sources it became known as Glucozade.

Professor Pybus never benefitted from his idea, but the chemist did. He was William Walker Hunter, and his company traded as W. Owen & Son. It’s unclear when the name was Glucozade, and when it changed to Lucozade. In a note written in 1974 Pybus definitely referred to it as Lucozade. The “ade” part made it clear that it was a soft drink, like lemonade or orangeade. It also suggested aid, as in assistance, first aid, or aiding the sick. This provided one of Lucozade’s most famous and catchy slogans in the twentieth century: “Lucozade aids recovery”.

In 1938 the famous pharmaceutical company of Thomas Beecham bought the recipe from Hunter for £10,000. This was a substantial buy-out at the time and Pybus appears to have felt some regret at not being involved in the commercial side of a product that he had, after all, devised. It’s interesting to speculate on how many sick children in North East England didn’t realise that Lucozade had originally been developed on their home turf. I certainly didn’t know. It was simply a comforting part of being ill.

Lucozade carried on being sold in its crackly yellow wrapper until the 1980s. It continued to be a very acceptable bedside offering from sympathetic relatives to their loved ones at home or in hospital. However, its days as a product with vaguely pharmaceutical properties were coming to an end. The eye-popping quantity of sugary glucose it contained might have been appropriate for pale and wan invalids who really couldn’t even face a boiled egg. However, sugar (even if branded as glucose) was under severe scrutiny. Sugar was out, sport was in. Lucozade rebranded as an energy drink, with a rather clever new slogan that still gave a hint of its previous application: “Lucozade replaces lost energy”.

From the 80s to the present day, Lucozade has sold its drinks in plastic bottles and cans. They now comes in many flavours and varieties, from Energy and Sport Lucozade, to the high caffeine Lucozade Alert and Zero Sugar Lucozade. What would Professor Pybus have made of the last, one wonders? A can of regular Lucozade today contains caffeine, carbonated water, glucose syrup (11%, which is still pretty sugary!), orange juice, citric acid, and sodium gluconate, which is an acidity regulator.

Beechams became part of the massive GlaxoSmithKline empire, and Lucozade made its final migration from a quasi-medical beverage to a modern sporty soft drink when it became part of the Suntory food and drinks group in 2013. This giant company, set up by Shinjiro Torii in Japan in 1899, is one of the world’s largest food and beverage manufacturers and distributors. It owns some of the most famous and popular brands including iconic Lucozade.

So important was Lucozade, and another British favourite, Ribena, to the fortunes of the group that the arm overseeing these drinks was for some time known as Lucozade Ribena Suntory. The company also supports the Lucozade Sports Science Academy, and is a leading sporting sponsor of individuals, teams, and trophies. Lucozade supports many athletes, from Michael Owen to the McLaren Formula One team, the Republic of Ireland Football Team, the England Football Team, and the FA Premier League and FA Cup.

It’s a long way from the vision of one Newcastle surgeon to provide an energy-supplying drink for extremely sick children, and from the local chemist’s in Barras Bridge that produced it. Lucozade is now a famous global brand, and that’s a great success story. However, I’m sure there’s more than a few people who look back on the days of the crinkly cellophane wrapping and bumpy glass bottle with some wistful nostalgia.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 25th July 2024