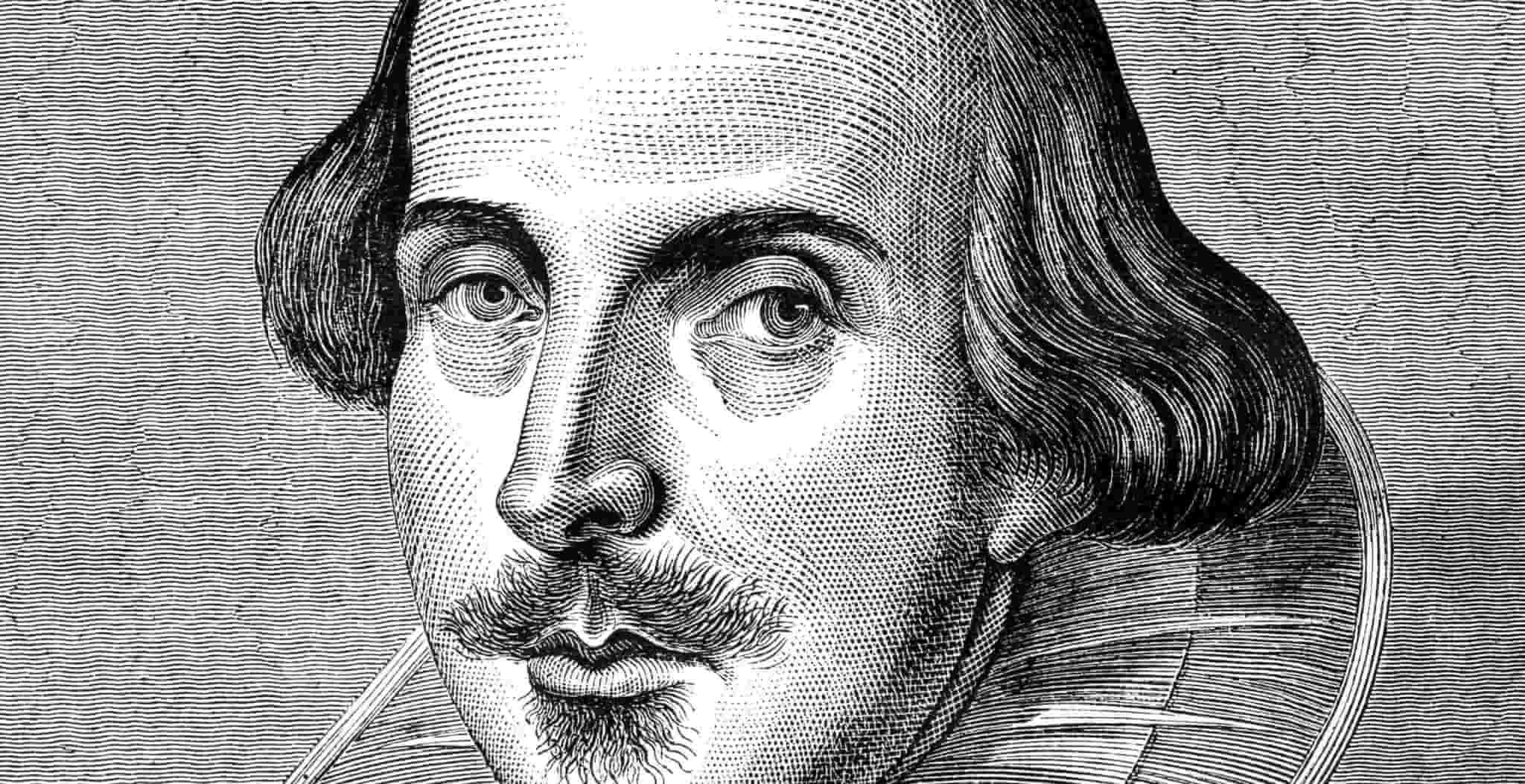

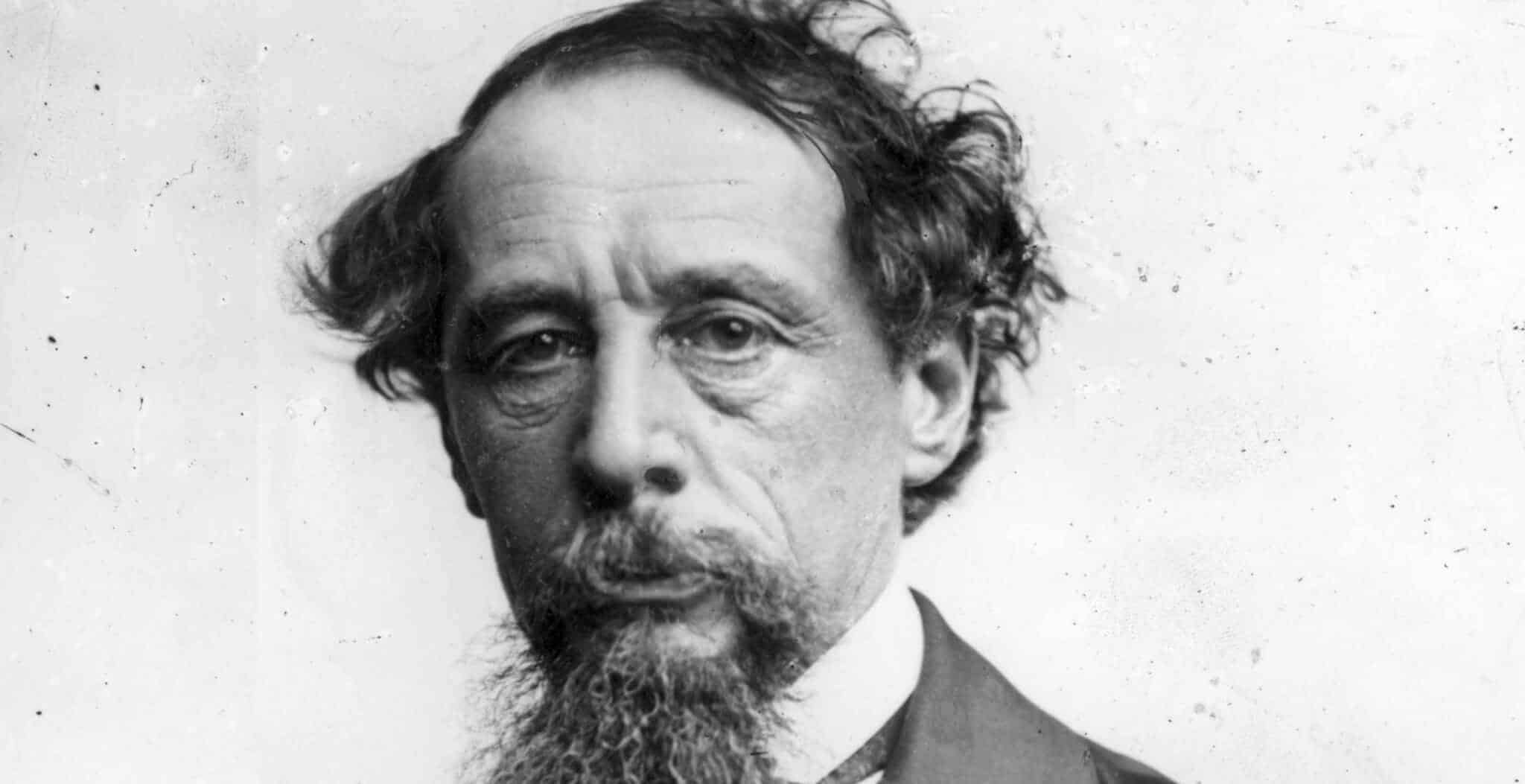

Fans of Jane Austen will be well acquainted with that hub of the Georgian social scene, the Assembly Rooms. In ‘Pride and Prejudice’, the local gentry first meet Mr Bingley and his party at the Meryton Assembly, and the Bath Assembly Rooms feature in both her novels ‘Persuasion’ and ‘Northanger Abbey’. Jane was writing from experience when describing the Bath Assembly Rooms: she lived in the city with her parents and sister from 1801 to 1805.

In Georgian society, most entertaining took place at home. Gentlemen would sometimes visit coffee houses or the new gentleman’s clubs, but ladies would gather in the home. Assembly rooms were one of the few public places where it was socially acceptable for both sexes to meet, dance and enjoy themselves.

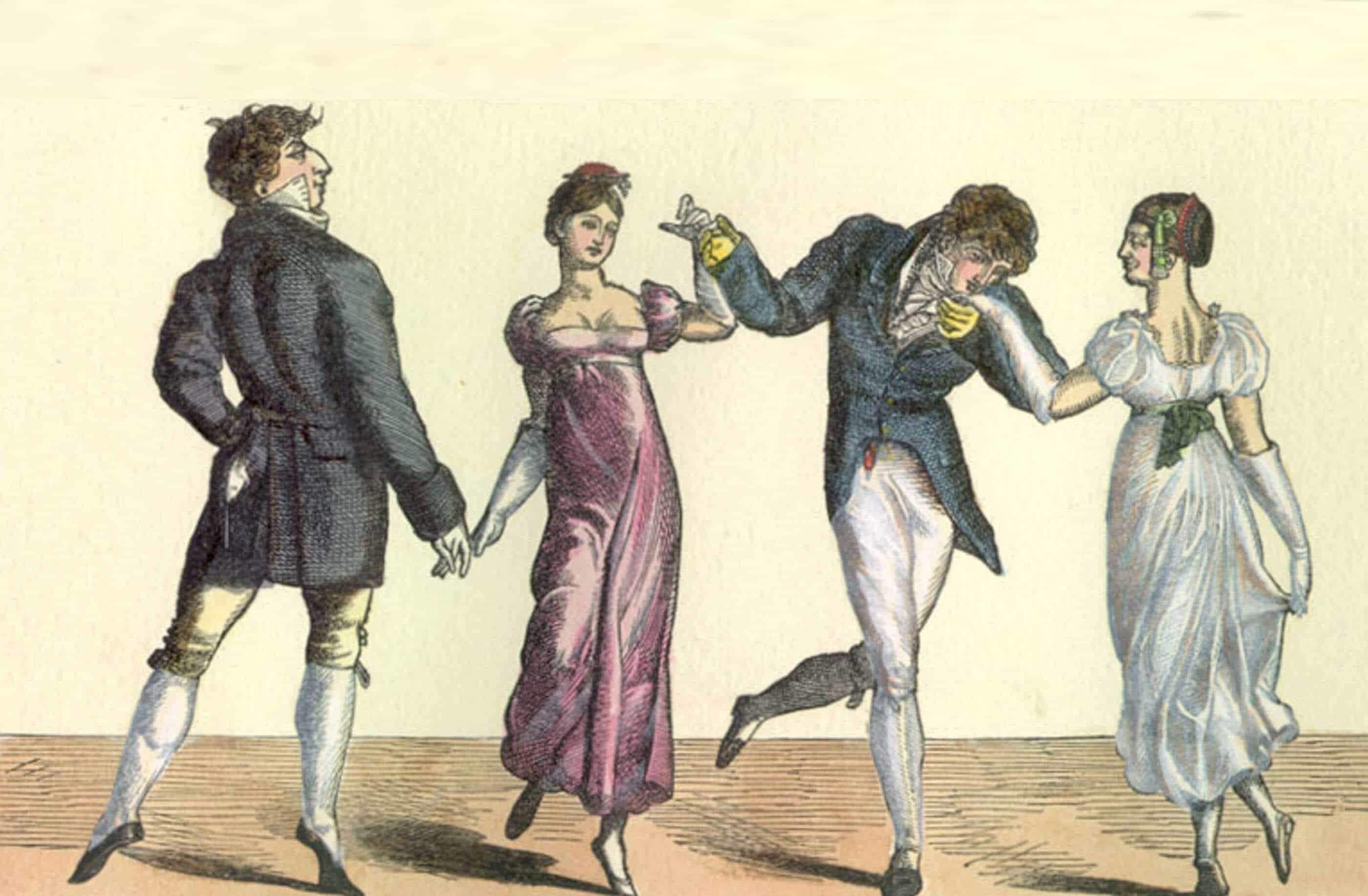

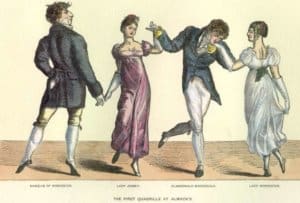

Mothers would bring their daughters to meet eligible young men here. This was done under a strict set of social rules: girls were chaperoned by a relative or family friend and not allowed to dance too many dances or spend too much time with the same gentleman as this could harm her reputation. Formal introductions, if necessary, would be made by the Master of Ceremonies. Of course not everyone came to dance and flirt; some came to meet up with friends and acquaintances, to gossip and play cards.

Assembly rooms varied from place to place, from large establishments with several entertaining rooms in spa or county towns, to perhaps just a single room above an inn in small provincial towns. The most famous were the Bath Assembly Rooms, completed in 1771.

Country assemblies were less formal gatherings than those in town and were attended by the local gentry. These were usually held above the best inn in the town and often coincided with local events such as country fairs, the assizes or horse racing. In the winter, assemblies were usually held monthly and timed to coincide with a full moon, making it easier to travel to and from the venue in the dark. The dancing would take place typically between 8pm and 11.30pm and would consist of country dancing, the cotillion, scotch reel and quadrille. Only light refreshments would be served unless the event was a special occasion.

Entry to the assemblies was by subscription, which might cost just £1 for the season in the country but as much as ten guineas in London. A Master of Ceremonies oversaw the running of the assembly, including enforcing any dress code and even ‘running the door’ to keep out any undesirable guests. He also made sure that gentlemen left their swords at the door!

Perhaps the most famous Master of Ceremonies was Richard ‘Beau’ Nash at Bath. His rules for polite behaviour made Bath one of the most fashionable places in Georgian England.

Formal assemblies and the associated assembly rooms fell out of fashion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Public dance halls, hotel ballrooms and nightclubs grew in popularity as attitudes towards upper class women attending these places became more relaxed. The age of the Georgian assembly room with its rigid social rules was over.