Bonfire or Fireworks Night is a uniquely British event. It commemorates the successful foiling of a plot to blow up King James I and Parliament by Catholic subversives in 1605. The fireworks are a reminder of the gunpowder that was placed by the plotters under the Houses of Parliament.

In 21st century Britain, Bonfire Night is usually celebrated with a trip to an organised bonfire and firework display, with paid admission and controlled access.

Not so in the 1950s and 1960s. Bonfire Night was a hands-on celebration. Family bonfire parties and get-togethers with neighbours were the thing. And as for health and safety: well, apart from the annual safety lecture on BBC’s ‘Blue Peter’, common sense was the order of the day.

Families started to collect wood for their bonfire at the end of summer. The trees in the garden would be trimmed and the branches piled up ready for the big day. Any old planks of wood, doors or other combustibles would also be added to the heap.

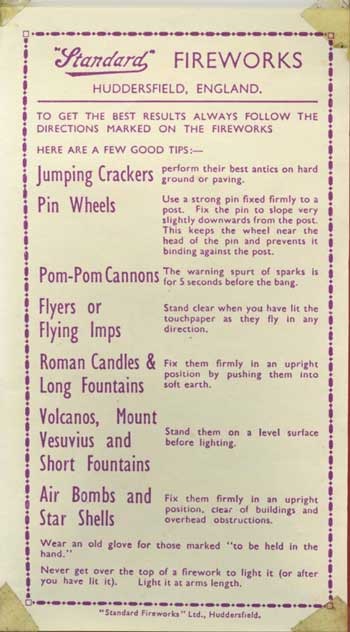

Fireworks appeared in the shops a couple of weeks or so before November 5th. There were selection boxes of fireworks (the most popular brand were Standard Fireworks) or you could buy rockets and larger fireworks one by one. Catherine Wheels and Roman Candles were particularly popular, as were sparklers and bangers.

Bangers were small tubes of gunpowder that after lighting, were thrown on the ground to explode with a loud bang, not unlike a miniature stick of dynamite! These are now banned from sale in the UK, as are Jumping Jacks, another Bonfire Night favourite. Once lit, Jumping Jacks lived up to their name by jumping about erratically. Far too much temptation for mischievous children wanting to give their friends a surprise!

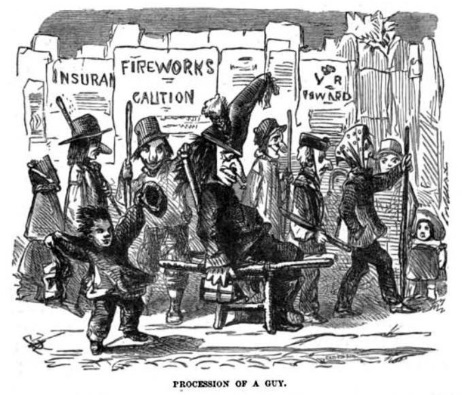

‘Penny for the guy’ was the cry on the streets. The guy, an effigy of Guy Fawkes, would be made from straw and dressed in old clothes, and often displayed in a wheelbarrow to be pushed around the neighbourhood. The money raised by the children would then be spent on bangers and other fireworks. However, following new laws in 2004, it is now an offence to supply fireworks to anyone under the age of 18.

A procession of children and a “Guy”, 1864

Neighbours and friends brought food to share at the bonfire parties – treacle toffee, toffee apples and parkin, a kind of gingerbread. Potatoes were roasted in the ashes of the fire and served with butter and salt, and eaten with a teaspoon in gloved hands. Never successfully baked, they always somehow tasted delicious in the cold night air. Mugs of hot soup would warm the audience around the fire.

These were the days of one bath a week for most families – usually a Sunday night – so if Bonfire Night should fall on a Monday or Tuesday, everyone would reek of smoke and fireworks for the rest of the week!

The bonfire was usually in the charge of the men of the house in those days and was quite a competitive thing with the neighbours. A fire had to be a ‘good fire’, preferably larger and brighter than next doors.

The night before Bonfire Night is traditionally known as Mischief Night, particularly in the north of England. In the 1960s this was a night when the local children would play pranks: knock-and-run on neighbour’s front doors, letting down car tyres, tying metal dustbin lids to door knockers – even changing the numbers on gates to confuse the postman! It was also the night when children would pilfer the best wood from rival bonfires unless they were guarded carefully.

On November 5th, as soon as it was dark, the fun would begin. The guy would be placed carefully on top of the wooden pyre before lighting. If it had been raining over the past few days, the wood might be wet and difficult to light. It has been known for paraffin to be used as an aid to lighting – with the resultant fireball taking out the neighbour’s hedge!

The boxes of fireworks would be kept under the careful care of an adult. The glow of a cigarette would be used to light the fuse on the fireworks. A Catherine Wheel would be nailed to a wooden fence or a tree – often a recipe for disaster, as if not nailed securely, they had a habit of launching themselves into the air, still spinning!

Contents of a Standard Fireworks box circa 1950s, © M Makepeace

Each child would be given a sparkler which was great fun to write in the air with until it spluttered and went out. Rockets were launched from glass milk bottles; they went off in any or all directions. The next day the remnants of the rockets – the wooden sticks – were to be found in gardens, on the pavements and in the streets and were often collected by children on their way to school. The ashes from the bonfires would smoulder for days afterwards.

Nowadays, stricter rules on the sale of fireworks and safety campaigns have persuaded many families that it’s safer to leave it to the experts and attend an organised display – much to the relief of fire and ambulance crews!