When philanthropist Henry Mayhew visited the Peek Frean biscuit factory in Bermondsey in 1865, he marvelled at the automation of biscuit production and “…how it can be possible to fabricate, out of a mass of puffy, unwieldy dough, ‘Ladie’s Fingers’ and ‘Tops and Bottoms’, by a series of cog-wheels and cranks.”

Henry estimated Peek Frean’s machines churned out 1.5m million of their popular but plain Pic Nics every week. He wondered how biscuits – “such a dry and juiceless food” were so popular they required a mechanical factory process to keep up with demand.

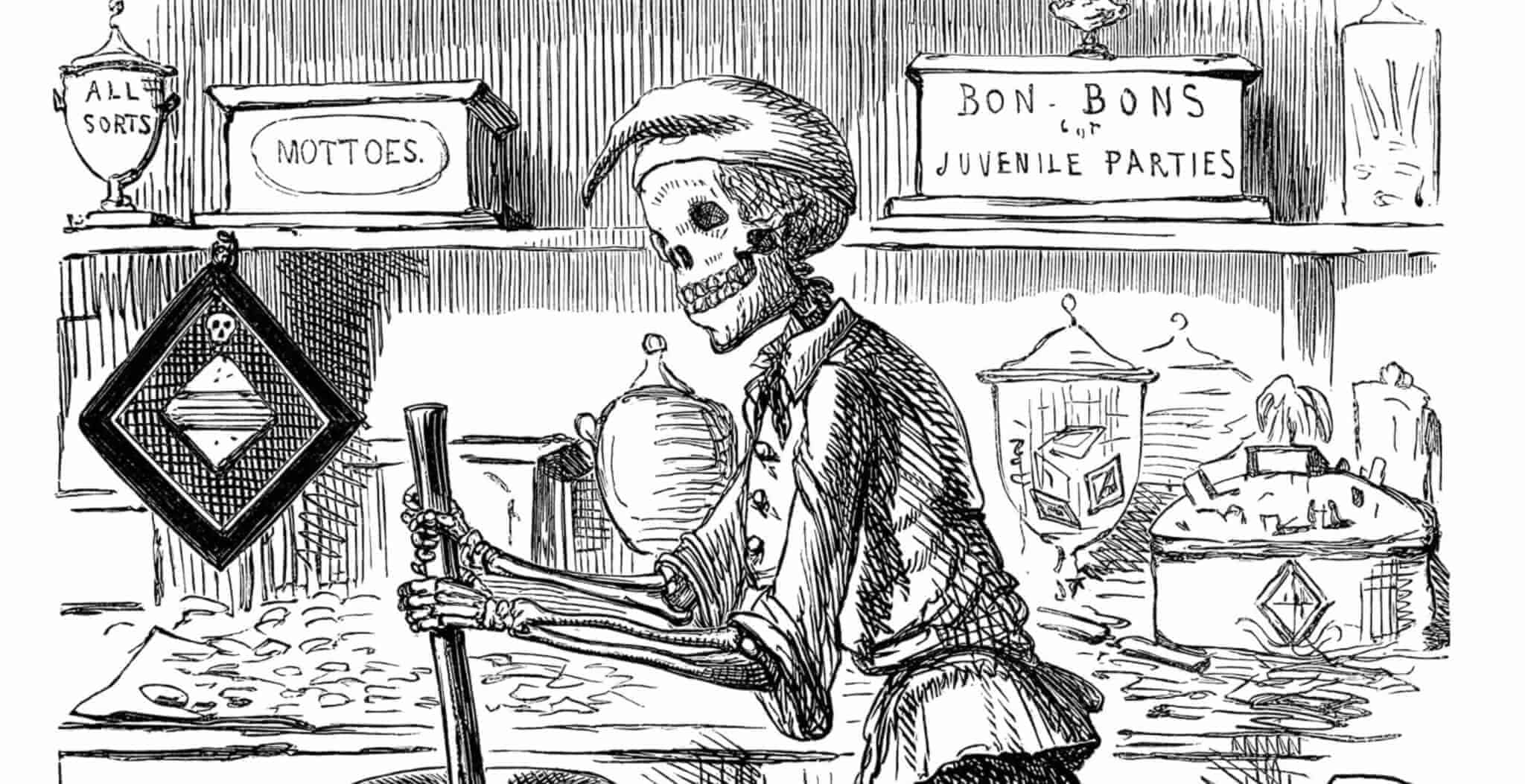

But it was precisely this mechanical process which made the biscuit so popular. Adulterated food was rife and feared in Victorian England but the clean, crisp and uniform mechanised biscuit not only looked superior but manufacturers could boast they were untouched by the human hand until the point where they were wrapped in paper and packed into boxes ready for distribution to grocers or merchant ships.

Biscuit manufacturers made it clear their ‘fancy’ biscuits were made using quality ingredients: twice refined white flour, sugar, butter and milk and then flavoured with orange, lemon, almonds, ginger or cinnamon.

Needless to say, these fancy biscuits could only be bought by those who had the money to spend on prepared food stuffs. But as the upper classes had cooks to make high quality biscuits for them, it fell to the middle classes to purchase a Carr’s Rich Desert or an Iced Rout. And purchase them they did. A biscuit rapidly became an acceptable snack to offer guests with tea as it required little mastication or digestion, far more suitable for ladies. In far reaching corners of the Empire, the fancy biscuit offered a little taste of home.

The industrialised process also hastened the development of the savoury biscuit. A new type of thin, flat, savoury biscuit – what we’d call a cracker nowadays – became a popular snack when served with sausage, cheese or fruit. Sometimes flavoured with salt, pepper, chives or rosemary, the savoury biscuit became a popular choice to serve with cheese and celery at the end of a meal to cleanse the palate before port was served. Jacobs of Dublin created the cream cracker for precisely this reason.

In order to have a fresh biscuit at the ready for hungry visitors, it was logical to store them in tins. Huntley and Palmers in Reading started the trend of dedicated biscuit tins as early as 1842 when the company produced tins in which to pack the biscuits for export; these proved popular as the tins kept the biscuits fresh and breakages to a minimum, and so it wasn’t long before Huntley and Palmers were producing decorative biscuit tins for customers to store their biscuits in at home.

But it was the licensed grocers act of 1861 which allowed groceries to be individually packed and stored ready for sale that enabled manufacturers to solidly concentrate on packaging their pure, unadulterated biscuits into fancy and commemorative tins ready for purchase and gifting. Early styles of these biscuit tins were usually square or oblong, printed with a pretty pattern and filled with a selection of biscuits.

It quickly became unfashionable to blatantly advertise the biscuit manufacturer on the tin, especially as many biscuit makers were Quakers and uncomfortable with pushy sales tactics, and so highly decorative biscuit tins with a smaller trademark were produced, so a housewife would be happy to display the tin as an ornament or reuse the tin around the home. As well as being used to hold sewing materials, stationery, even shoe cleaning products, biscuit tins were used as ballot boxes in Switzerland and storage safes for bibles in Uganda.

Towards to end of the nineteenth century, British biscuit tins became more and more ornate as their popularity grew. New designs were released for special occasions such as Queen Victoria’s Golden and Diamond jubilees, but it was at Christmas the biscuit tin really came into its own.

As the celebration of Christmas became more entrenched in Victorian Britain, biscuit companies began to produce specially designed tins of biscuits for the season. These were advertised through colour printed Christmas catalogues, picked up by a housewife at the grocers and which she could then browse at her leisure – possibly over a cup of tea and a biscuit – choosing a gift for a family member or friend, or debating which tin of biscuits to have on hand for hungry Christmas visitors. The Victorian biscuit tins were not always Christmas or even winter themed though. Designs from Huntley and Palmers 1906 Christmas catalogue include tins in the shape of a globe of the world, a stack of books, a red pillar box and a woven basket.

The business of gifting tins of biscuits for Christmas has since become a British national habit. Although boxes of assorted biscuits are available all year round, biscuit manufacturers still produce commemorative tins of biscuits for Christmas, which are on the shelves in shops by November. Many are Christmas themed, such as Marks and Spencer’s Santa’s Workshop Musical Light Up tin and Fortnum and Mason’s Merry Go Round musical biscuit tin. Marks and Spencer have also released this year a ‘Letters for Santa’ mailbox – shaped tin with cookies, clearly aimed at children and advertised as ‘perfect for stockings.’ Meanwhile, Fox’s continue to advertise their biscuits with the “Fox’s since 1853” strapline, reassuring the modern customer that they know how to produce tasty biscuits and the original Victorian quality remains undiminished with time.

Shona Parker is a history writer and blogger. Her first book “How the Victorians Lived” is published by Pen and Sword and is widely available. You can read more of her writing at www.backinthedayof.co.uk.

Published: 8th January 2025.