In the UK, approximately 1 in 8 women have an assisted vaginal birth.

Although the use of forceps is now common, it has not always been accessible to women for a variety of bizarre reasons.

One family has been accredited with the invention of forceps: The Chamberlens.

Peter Chamberlen the Elder (1560-1631) was a barber surgeon with an interest in midwifery and became known as a ‘man-midwife’. He is believed to be the inventor of the forceps. However, both Peter the Elder and his brother, Peter the Younger, saw that this invention was kept a secret for approximately two centuries.

Why did the Chamberlen’s keep their invention a secret?

The Chamberlen family wanted to bring the licensing and control of midwifery under themselves, through the creation of a midwifery college of which they were the founders. However, the idea was rejected by the College of Physicians in 1647.

Peter Chamberlen the third (1601-1683), the son of Peter the Elder, repeatedly attempted to revive his father’s idea of a corporation of midwives but he lost support from midwives and the College of Physicians rejected his attempts.

Peter Chamberlen. Line engraving by T. Trotter, 1794, after R. White.

Mistitled as Paul Chamberlen. Wellcome Library, London.

How the Chamberlen’s kept their secret for so long was quite strange, as many would think that it would be difficult to keep forceps a secret, considering that the woman would feel the instrument!

They would transport the forceps in a large, gilded box that required two people to carry it, blindfold the labouring woman and send away all those attending.

The Chamberlens kept attempting to profit from their invention, with Peter the Younger’s son, Hugh the Elder, traveling to France to sell the forceps. However, he was unsuccessful as he was told to deliver the child of a woman who had dwarfism and had been in labour for eight days. He was unsuccessful, the woman died, likely from a ruptured uterus, and no sale was made.

Their secret was uncovered in 1733 when Hugh Chamberlen the Younger did not produce a male heir, therefore he is suspected to have been the leak.

A Scottish doctor known as William Smellie (5th February 1697- 5th March 1763), was a great pioneer in the field of obstetrics. He modernised the Chamberlen forceps with his ‘English lock’ and made the blades better suited to female anatomy…. which he studied and made notes about!

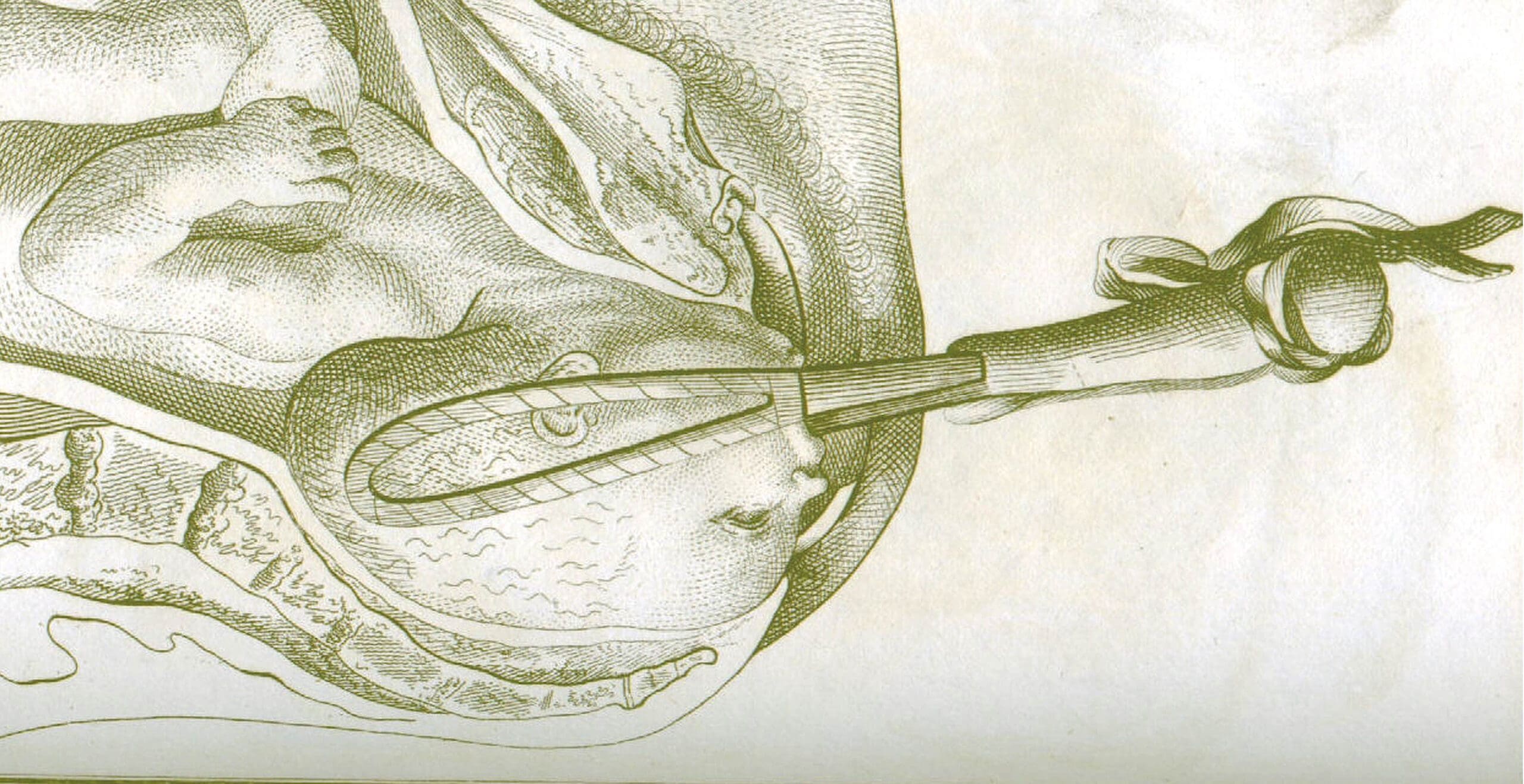

Baby and Forceps. From William Smellie’s “A Set of Anatomical Tables”.

Baby and Forceps. From William Smellie’s “A Set of Anatomical Tables”.

Smellie wanted to teach people how to use forceps correctly and so he created an accurate phantom model of the female pelvis, which was highly important as knowledge of the female anatomy was, and to some degree, still is, overshadowed by the focus on the male anatomy which has been treated as the default body.

Smellie is also accredited with being the first person to resuscitate an infant after lung collapse, as well as being the first person to document the natural birthing process. Smellie had 900 pupils and delivered 280 lectures a decade after establishing his London practice.

However, he was not without criticism.

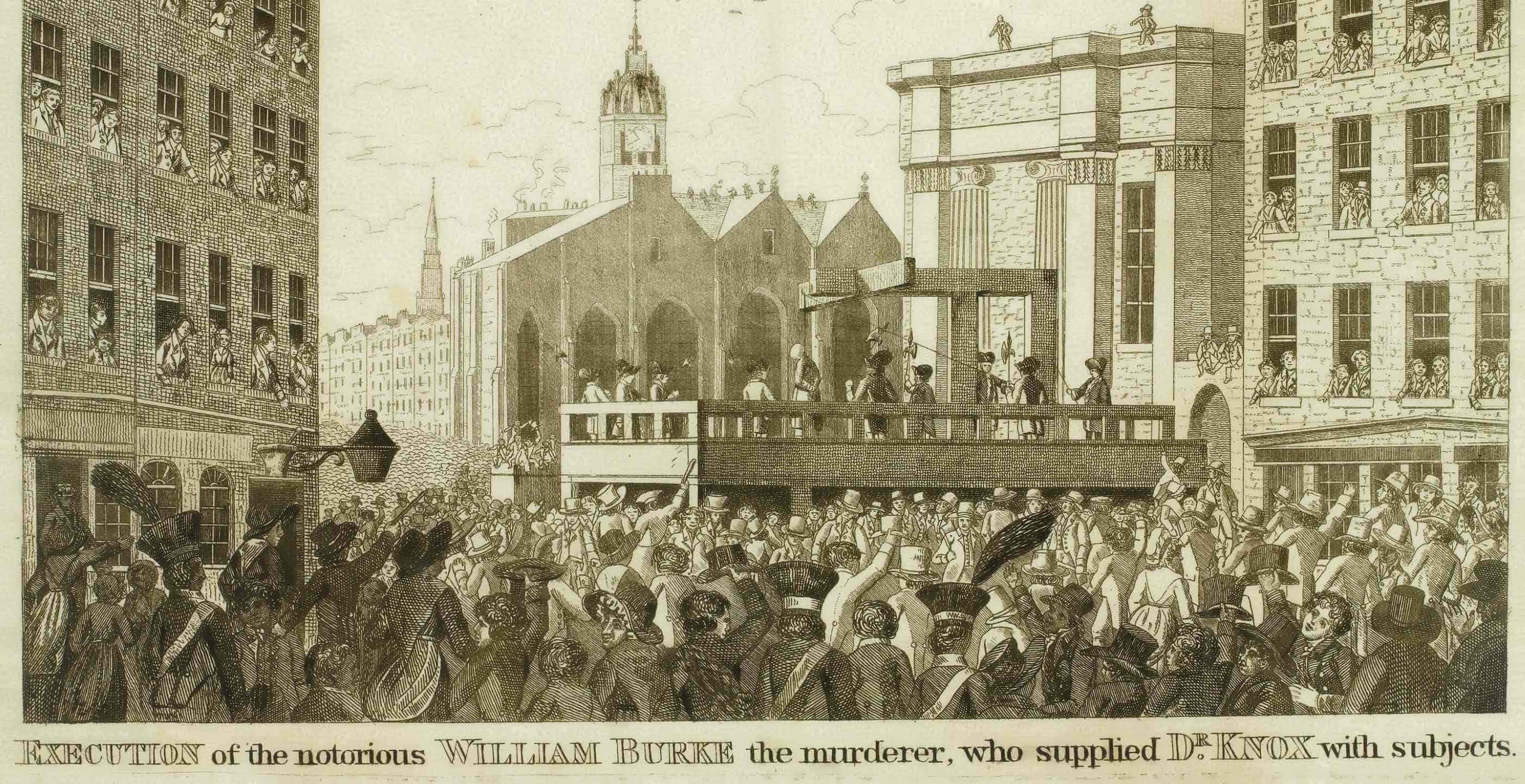

In 1755, Smellie was questioned regarding his access to corpses by his competitors, which caused him to stop his work for several years as he was at risk of being executed.

Smellie faced further criticism as midwifery was a female-dominated profession, particularly amongst the working-class as man-midwives generally worked for the upper class, and many poorer patients believed it improper for men to assist women in childbirth.

There was also a reluctance to use forceps, which Princess Charlotte of Wales, only child of George IV, fell victim to as she haemorrhaged to death after a 50-hour labour and delivery of a still-born boy. Forceps were held on standby during the labour but not used. Her obstetrician committed suicide shortly after her death.

Princess Charlotte of Wales

It is unlikely forceps would have saved her life, however there was very strong criticism from the public when it was discovered no one attempted to use them.

Being a pregnant woman has historically been, and continues to be, risky. Especially when there was no NHS and you were impoverished.

Smellie managed to alleviate some of this, as he offered free midwifery services on the condition that his medical students could see the birthing process. However, the appropriateness of this demand, at a time where a woman saying no might end with her dying in childbirth, is unlikely to pass an ethics board today.

Death in childbirth occurred mostly in young, healthy women who were healthy prior to pregnancy and in the late 18th century it is estimated that the maternal mortality rate was 25 per 1000 in unassisted women. In modern British society, it is now 11.56 per 100,000.

Midwifery and medical instruments were not properly regulated and the working-class had to rely on a handy-woman, who would have no knowledge on how to use a pair of forceps (yet could purchase them) as women could not become doctors until 1876.

And that was only if you had the money to train to become a doctor.

Because women were heavily relied upon in birthing situations for the poor and yet were effectively banned from gaining an education in the subject, they used forceps. This, of course, led to death and disability from a lack of training and poor regulation of medical instruments.

It was the 1902 Midwives Act that solidified the legal standing of the profession and lead to the creation of the Central Midwives Board, which regulated midwifery practice and formalised education in England and Wales.

Forceps have saved many lives; it is unfortunate to think of how many people could have survived if greed, sexism, and classism hadn’t prevented their widespread, educated usage.

Claudia Elphick studied History, Literature and Culture at the University of Brighton and graduated with a first class undergraduate degree. She went onto complete a Criminal Law and Criminal Justice LLM at the University of Sussex via the Chancellor’s Masters Scholarship programme.

Published 3rd October 2023