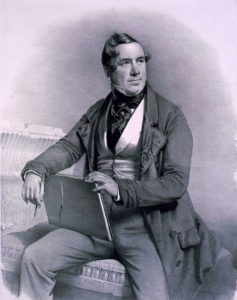

The Scottish artist David Roberts (1796 – 1864) is probably best known for the series of commercial lithographs produced after his journeys to Egypt and the Near East. His romantic, yet finely detailed landscapes and townscapes have appeared in many volumes of Egyptian and Near Eastern history and art, and he is recognised as one of the leading Orientalist painters of the period.

What is less well-known is his career as a painter of stage scenery, including material for the Dioramas that were a popular entertainment of Georgian times. In fact, Roberts began his career at the age of 10 as an apprentice to a painter and decorator.

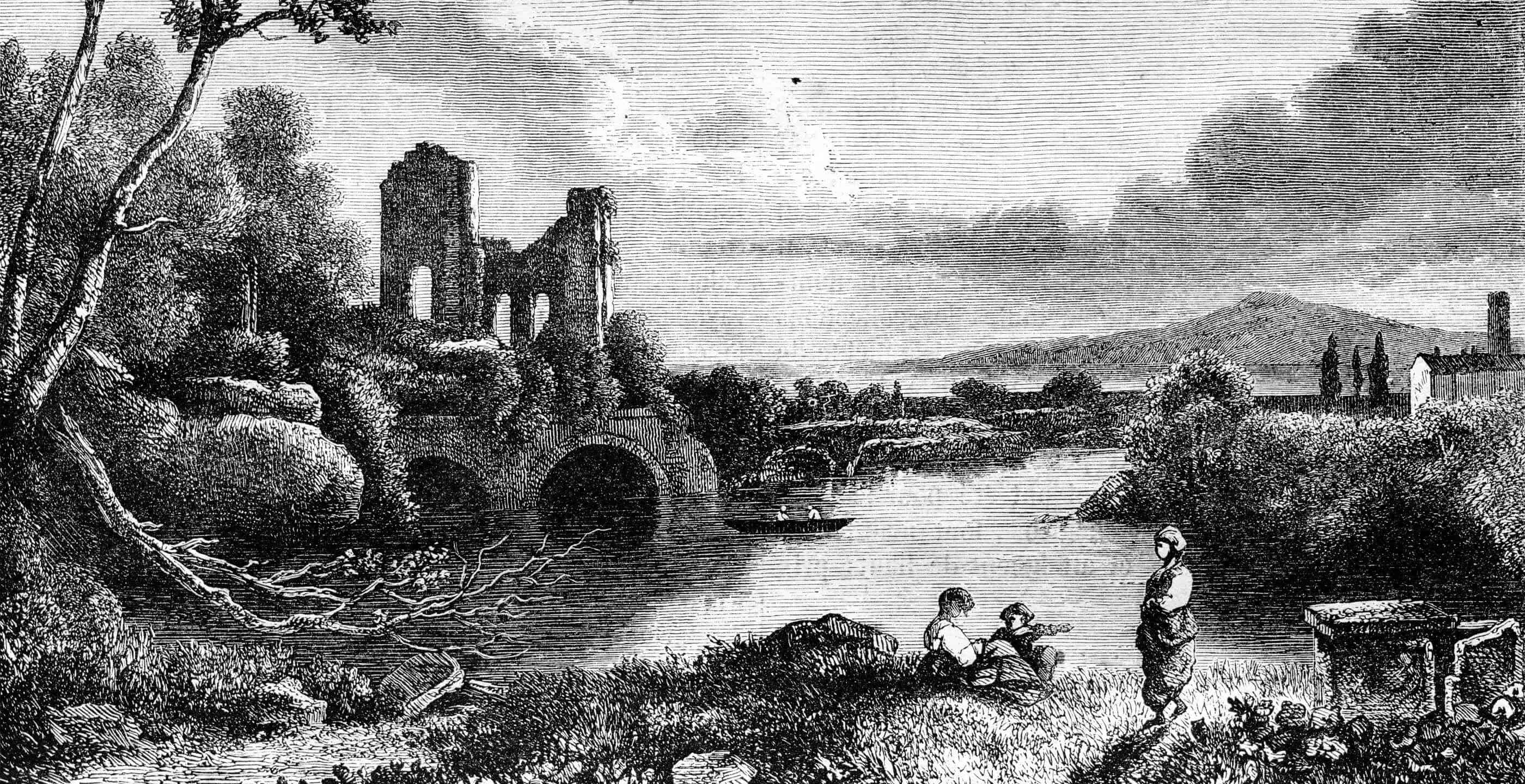

Roberts was born in Stockbridge, near Edinburgh, and while a boy he was a frequent visitor to nearby Rosslyn Chapel. Rosslyn’s architecture is a complex fusion of influences from many cultures, and the scholar Angelo Maggi, an expert on the history of the building, has suggested that it was an immense inspiration to the painter and “Roberts’s gateway to the Near East”. The Chapel would certainly play an important role in his life and he would eventually become a campaigner on its behalf.

At the age of 19, after studying art formally at night, Roberts became foreman of work at Scone Palace for a time. Returning home in search of a new job at the end of the project, he took work as a scenery painter for James Bannister’s circus. Bannister offered him more work, engaging him on a good salary of 25 shillings a week, and for a while Roberts toured the country with the circus.

Through Bannister, Roberts then found work at the Pantheon Theatre in Edinburgh, but when the venture failed, he returned to his trade of house painter and decorator. All the time he was working on the “day job”, he was also practising his sketching and painting, thus developing his fine art skills.

Roberts returned to painting scenery for theatres in Edinburgh and Glasgow, meeting his wife, the actress Margaret McLachlan, at the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh. They had one child, Christine. In the early 1820s he exhibited work at the Fine Arts Institution in Edinburgh, including scenes of the abbeys of Melrose and Dryburgh, which were popular themes due to the immense interest in the history of the Anglo-Scottish border created by the work of Walter Scott.

Roberts was offered work in London, at first by the Coburg Theatre and then the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane. He developed a working partnership with William Clarkson Stanfield, and together they began to create works for the Dioramas that were proving so popular in London and Paris. In fact, it’s likely that Roberts was the “young Scottish artist” referenced with regard to the Edinburgh Diorama that opened as early as 1824, shortly after the Regent’s Park Diorama.

St. Mungo’s Cathedral, Glasgow

St. Mungo’s Cathedral, Glasgow

Soon Roberts was commissioned to work for Covent Garden, while also successfully exhibiting at the British Institution. Gothic, romantic and religious themes were still popular in art and Roberts continued to produce paintings of Scottish abbeys and famous European cathedrals. He developed his range into landscapes and seascapes, as well as Biblical and antiquarian themes, achieving fame though his painting “Departure of the Israelites from Egypt”. In 1831, the young Roberts was elected president of the Society of British Artists.

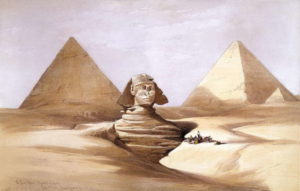

Roberts began to travel in 1832, producing a series of lithographs from his trip to Spain and Morocco. In 1838, he embarked on a tour of Egypt, Nubia, Sinai, Syria and the Holy Land, and his sketches, paintings and lithographs were hugely in demand on his return. Publication of “Sketches in the Holy Land and Syria, 1842–1849” and “Egypt & Nubia” followed, volumes that ran to many editions and are still popular as reprints today.

Head of the Great Sphinx, Pyramids of Geezeh (1839)

Head of the Great Sphinx, Pyramids of Geezeh (1839)

Rarely had background, talent, experience and subject worked so well commercially for any artist. The experience Roberts had gained as a scenery painter was the ideal education to do justice to the size and atmosphere of the temples of Abu Simbel, the pyramids of Giza, the remains of Luxor and Karnak, and the giant statues of Memnon. His style evoked mystery and drama and the impression of immense and impenetrable antiquity.

When he returned to Scotland, the Royal Scottish Academy feted him at a public dinner. As a result of this, Roberts advised the Academy that he was worried about work that was being done at Rosslyn Chapel. One of the major architectural conflicts of the time was between the “romantic school” who viewed overgrown buildings as beautiful in their own right, even seeing the moss and overgrowth as protective, and those who wished to restore and preserve buildings. Maggi describes them as “two factions…wild nature lovers and building lovers”. Roberts was decidedly in the former camp.

The romantic view seems well-summed up in a painting by John Adam Houston of Sir Walter Scott sitting in a very dank-looking Rosslyn with green mould and moss clearly visible on the pillars. The disputes between the two groups grew extremely vituperative. It was an argument that would also extend to the monuments of other countries, as organisations such as the Egypt Exploration Fund began to raise money to preserve the monuments they perceived to be at risk.

It’s an argument that still continues today, with overtones of colonialism and disputes about how much preservation is really necessary. Ultimately, though, Roberts made a major contribution simply by recording what he saw at the time, in the period just before photography came in. His work succeeds in making accurate recordings that are also atmospherically imaginative and compelling.

The Giudecca, Venice (1854)

The Giudecca, Venice (1854)

Roberts also visited Italy in the early 1850s, producing a volume of paintings entitled “Italy, Classical, Historical and Picturesque”. The last 15 years of his life were spent carrying out prestigious projects such as the painting of the opening of the Great Exhibition in 1851. He became a member of the Royal Academy and was given the freedom of Edinburgh. His distinctive style and intuitive interpretation of light were emulated by many artists who came after him.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.