Standing proud amongst the encroaching vegetation in Bath’s Locksbrook Cemetery is a memorial to Dr John Forrest C.B., Inspector General of Hospitals and Honorary Physician to Queen Victoria. On his death in 1865, the Morning Post lamented the passing “of one of the best medical officers of the British army”. Highly regarded in military circles, he was also one of the few senior officers in the Crimea to gain the respect – and indeed the sympathy – of Florence Nightingale.

Grave of Dr John Forrest, Locksbrook Cemetery, Bath (Photo by Richard Lowes)

Grave of Dr John Forrest, Locksbrook Cemetery, Bath (Photo by Richard Lowes)

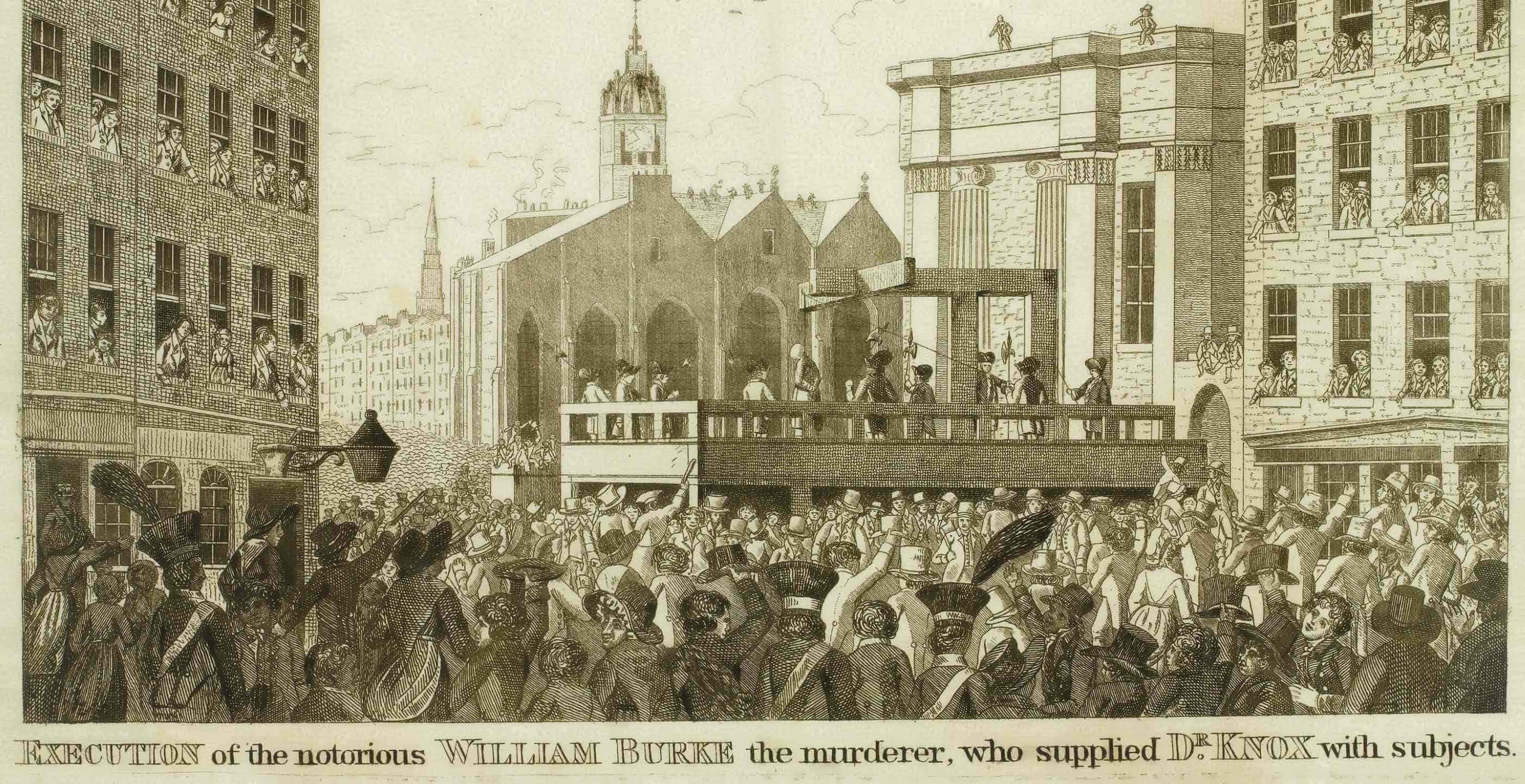

Yet, life might have turned out very differently for this distinguished son of Stirling. In 1822, as an 18 year old medical student at Edinburgh University, he was charged with “violating the sepulchres of the dead, and raising and carrying away dead bodies from their graves” – put simply, body snatching. To aggravate matters, he promptly absconded, possibly to Paris, and was declared an outlaw.

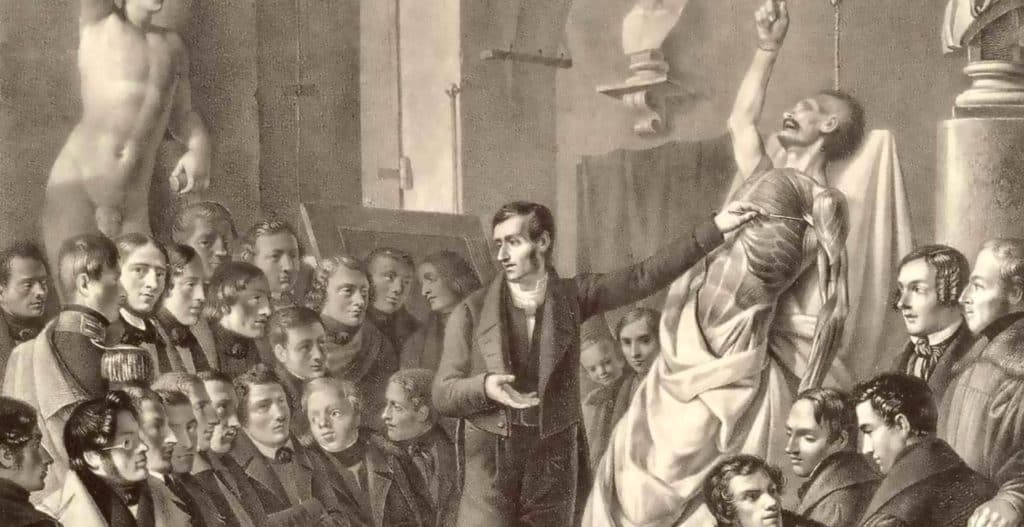

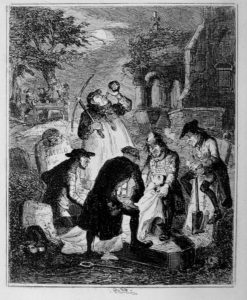

Resurrectionists (Hablot Knight Browne)

Resurrectionists (Hablot Knight Browne)

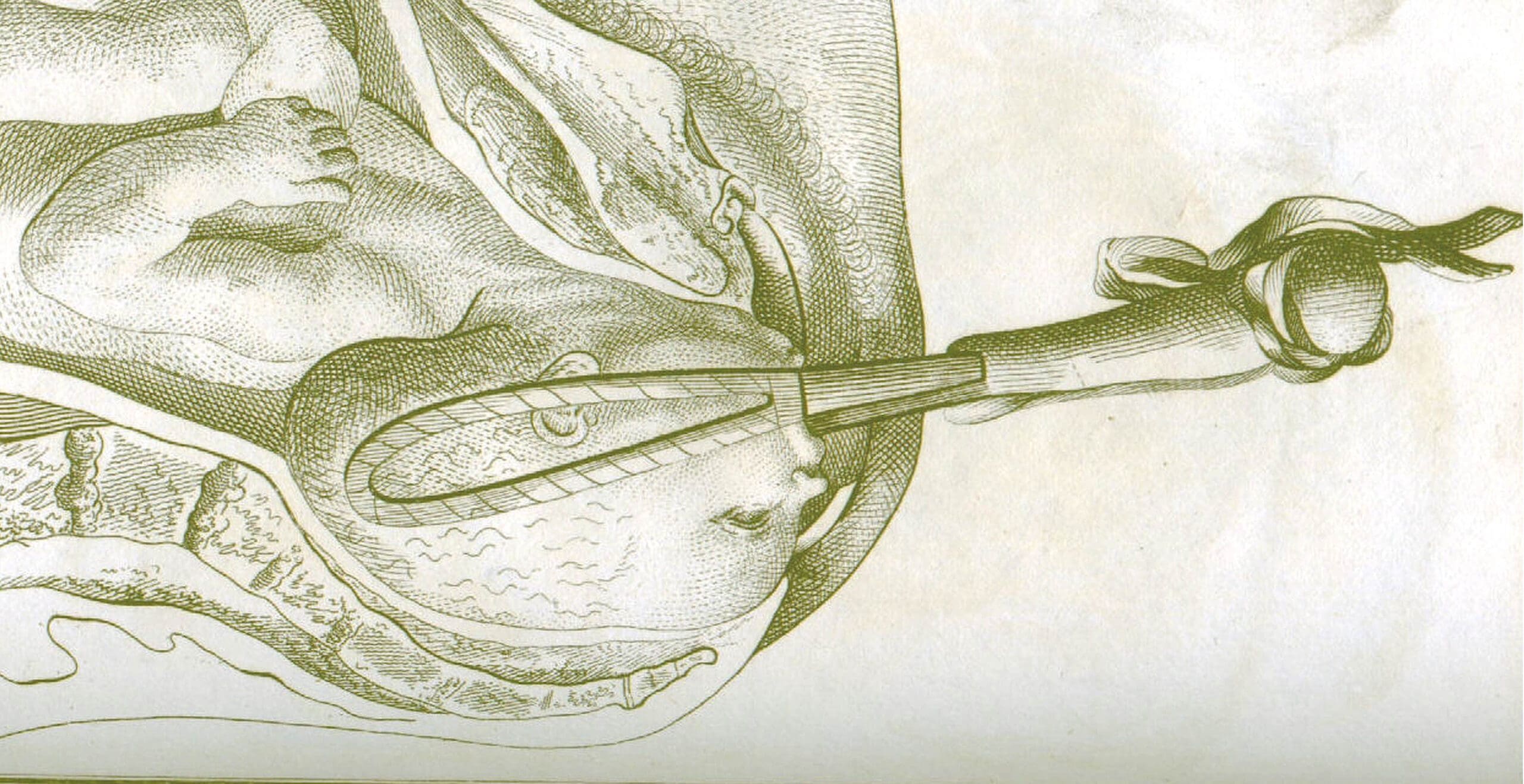

The early nineteenth century saw Edinburgh at the forefront of European anatomical study. But the demand for cadavers for dissection greatly exceeded the legal supply, which under Scottish law could come only from deceased prisoners, orphans, foundlings and suicide victims. This scarcity of corpses created a lucrative trade for the infamous ‘resurrection men’, who would purloin the recently dead from graveyards and morgues. Measures such as constructing mortsafes over graves to ensure bodies were left undisturbed only exacerbated the supply shortage, further increasing the price that anatomists would pay.

Mortsafes in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh

Mortsafes in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh

Forrest acted with at least two accomplices. Those indicted with him were Daniel Mitchell, a servant, and James McNab, the parish gravedigger. The trio were charged that on the night of the 23rd November 1822, they had entered Stirling Graveyard, “opened the grave, and carried away the body of Mary Stevenson, widow of the deceased Joseph Witherspoon, mason.”

As a medical student, Forrest’s motive in searching for a cadaver was the furtherance of his education, and there is little question that he was the instigator of the crime. Indeed, Mitchell and McNab lost no time in pointing the finger at Forrest, who, it was alleged, offered them up to four guineas each per body. As a key holder to the graveyard, McNab’s assistance would have proved invaluable, but he protested that he had left the scene before the gruesome events unfolded. Mitchell admitted to being present but claimed Forrest had got him drunk on whisky, and he was no more than an observer, leaving immediately afterwards.

When the matter came to trial, in Forrest’s absence as the undoubted ringleader, the judge halted proceedings pro loco et tempore, meaning the prosecution had the right to bring a fresh indictment against the accused later. As a result, McNab and Mitchell were immediately released.

Body snatchers were deeply unpopular, and news of their release spread swiftly. Soon, an angry mob gathered outside McNab’s home. A window was smashed, and a stone hurled at a terrified McNab, striking him on the head. Fortunately, a policeman arrived, and the half-senseless man was escorted back to prison for his own safety, running a gauntlet of stones the entire way.

According to the Caledonian Mercury:

By some miracle, Mitchell escaped but was pursued relentlessly through the neighbourhood until the Sheriff and Provost “accompanied by a file of men, and captain Jeffery of the 77th” intervened to save his life.

Ultimately, this whole sorry episode came to a rather unexpected conclusion.

Although in hiding and an outlaw, incredibly Forrest managed to continue his medical studies, qualifying in 1823 as a licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Then in July 1824, several newspapers carried the following announcement:

His Majesty has been graciously pleased to grant a free pardon to Mr. John Forrest, surgeon, who was outlawed at the Circuit Court of Justiciary, holden at Stirling in Spring 1823, for not appearing to answer an indictment charging him with aiding in the abstraction of a dead body from a churchyard.

Old Surgeons Hall, Edinburgh

Old Surgeons Hall, Edinburgh

Such a dramatic turn of events strongly suggests the intervention of a person or people of influence on Forrest’s behalf. Moreover, a royal pardon was particularly remarkable given the widespread strong feeling against resurrectionists.

In 1825, Edinburgh University conferred the degree of Doctor of Medicine on Forrest in recognition of his thesis on gangrene, a subject that would prove invaluable in his military career. Later that year, he joined the British Army, initially as a Hospital Assistant, shortly afterwards being promoted to Assistant Surgeon with the 20th (East Devonshire) Regiment. After serving in India and Scotland for several years, in 1839, Forrest moved to South Africa with the 75th Regiment in company with his wife. Shortly afterwards, he joined the Hospital Staff in Cape Town. His two children were born here, but sadly, he lost his wife in 1842.

Forrest was frequently frustrated at the slow progress of his military career, although a lucrative private practice in Cape Town was a strong consolation.

Eventually promoted to Surgeon First Class in 1850, Forrest returned to Britain. 1854 saw further promotion to Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals. Almost immediately, he sailed to join the expedition to Crimea where he distinguished himself at many of the major engagements, including Balaklava, the Alma, Sebastopol and Inkerman. Following the latter, Lord Raglan mentioned him in dispatches “for his able exertions”.

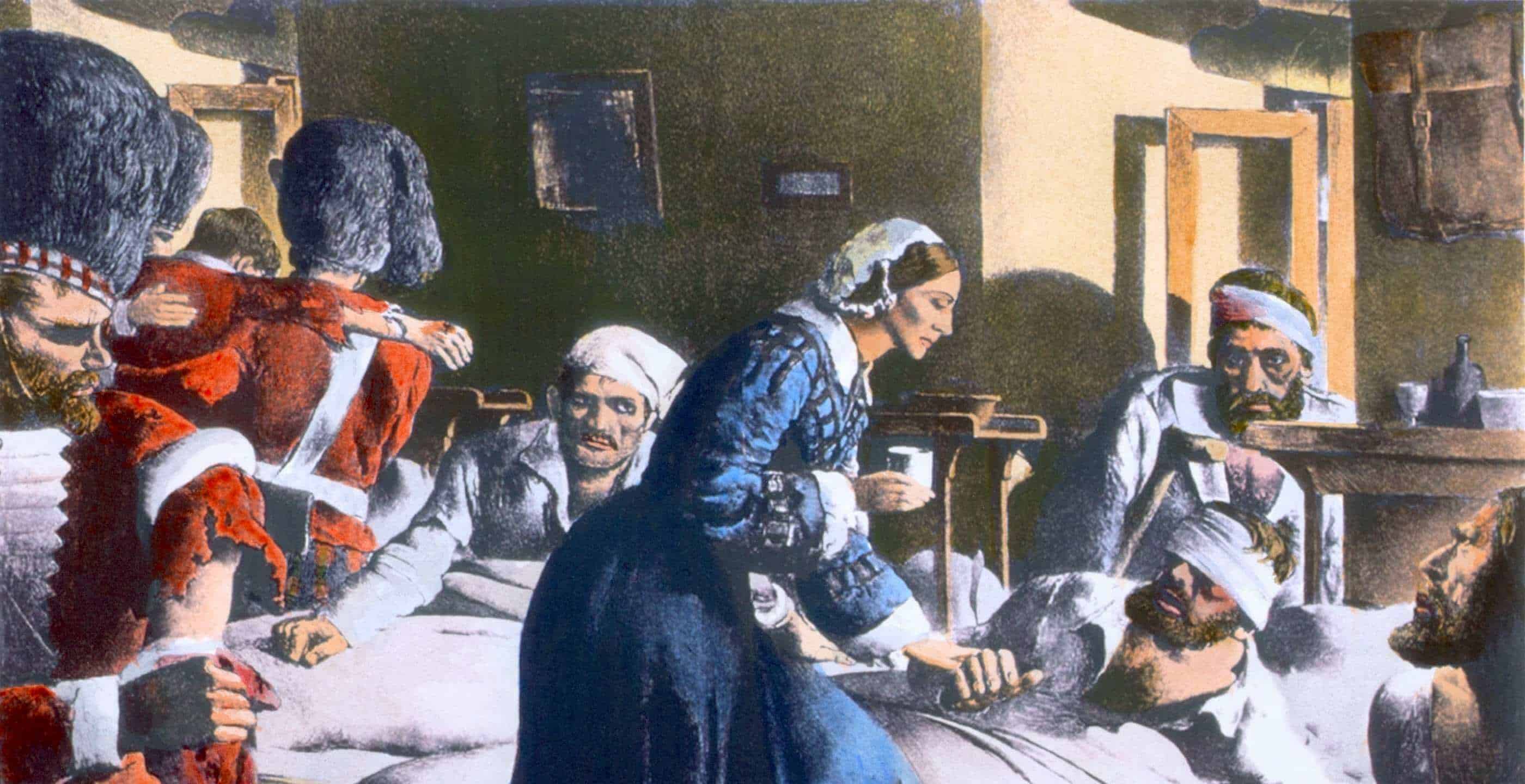

In December 1854, an exhausted Forrest was appointed Medical Superintendent of the notorious Scutari Hospital. He arrived a month after Florence Nightingale, who was working to improve the appalling conditions of almost five thousand sick and wounded men. Faced with such squalor, overcrowding and chronic staff shortages, Forrest wrote, “I fear that this place will prove too much for me.” In correspondence, Nightingale noted his desperation.

By late January 1855, Forrest was severely ill and sent to England to recuperate. By May, he had recovered sufficiently to be personally presented with the Crimea Medal with three clasps by Queen Victoria.

Medals of Dr John Forrest (Photo courtesy of Giles Forrest)

Medals of Dr John Forrest (Photo courtesy of Giles Forrest)

1858 saw Forrest’s final promotion to Inspector General of Hospitals, and in 1859, the former outlaw was appointed Honorary Physician to the Queen.

Posted to Malta as Principal Medical Officer, he won considerable further praise for implementing measures to improve the garrison’s poor health. Indeed, a new hospital there was named in his honour. But his own health had never fully recovered after the Crimea, and in 1861, he retired to his home in Queen’s Parade, Bath, where he died on 10th September 1865.

Richard Lowes is a Bath-based amateur historian who takes a keen interest in the lives of accomplished people who have passed under history’s radar.

Published: 13th December 2022