After the outbreak of civil war in August 1642, soldiers’ uniforms on the battlefield became windows into their hearts; in this divisive era, even hairstyles provoked fierce arguments. As a result, an exploration of seventeenth-century clothing quickly reveals that there is more to fashion than lace and leather: during the English Civil War, it influenced the fate of the nation.

Battlefield Fashions

According to the textbooks, Royalist and Parliamentarian soldiers could be identified on sight. The Royalist army (so they say) was composed of aristocrats and dandies: think flowing hair, feathered hats and copious amounts of lace. On the other hand, Parliamentarians are typically painted as simple country soldiers with Bibles under their arms, clunking leather boots and close-shaved heads (hence the nickname ‘Roundheads’).

But was it really so simple?

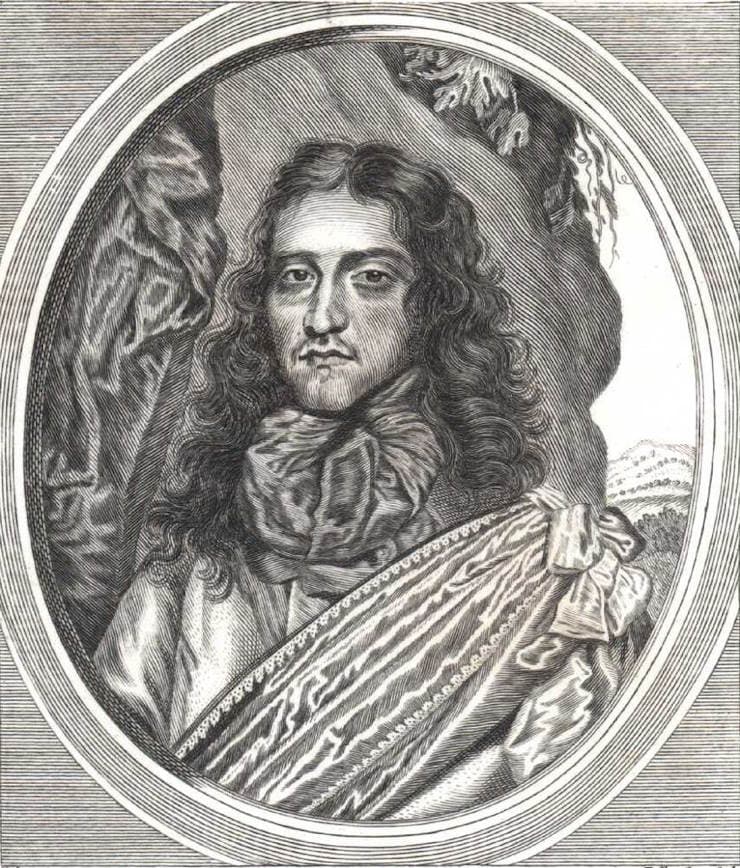

Certainly, the stereotypes are rooted in history to an extent. Just look at Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a flamboyant Royalist general who thrived on high fashion (and time with his pet poodle). He fitted the Cavalier cliché exactly. To top it off, he was also King Charles’ nephew: as a result, Rupert inevitably became a Royalist poster boy.

However, high-profile individuals like Prince Rupert tend to skew our perception of both armies. In reality, allegiances were far from straightforward: within every cross section of society, there was debate and division.

For example, the plain-clothed Puritan faction of the church was fiercely divided. Some, concerned by the king’s alleged sympathy with Catholicism, were staunch Parliamentarians; others, loyal to the king as God’s anointed monarch, joined the Royalist army.

As for the elaborately dressed aristocracy, many of them felt also obliged to fight for the king, as their wealth had benefited from the monarchy. However, there were exceptions. Nehemiah Wharton, for instance, was a dashing Parliamentarian sergeant. On the battlefield, he wore a scarlet outfit decorated with gold and silver lace – and hoped, in his own words, that he would ‘never stain [it] except in the blood of a cavalier’. As historian Diane Purkiss has pointed out, Wharton – the young romantic – was a far cry from the stereotypical rough-and-ready Roundhead.

As a result of these divided allegiances, the visual differences between Royalists and Parliamentarians were so indistinct that there was confusion on the battlefield. On occasions, friendly fire was reported.

It was only three years into the war that the Parliamentarians, at least, began to cultivate a distinctive visual image. When Oliver Cromwell masterminded his New Model Army, he famously spoke of his desire to have a ‘plain, russet-coated Captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows’. From that point onwards, a russet-coloured coat instantly signalled its wearer’s allegiance: in the words of Diane Purkiss, ‘It was as if they donned [the New Model Army’s] ideology with its red jackets’.

Battle of the Barbers

However, in the same way as a soldier’s coat reflected his beliefs, his hairstyle reflected his heart – and the wrong haircut could get him into trouble.

Colonel John Hutchinson, a high-ranking Parliamentarian, had fashionably flowing hair (‘clean and handsome’, according to his wife). His troops, however, religiously kept their hair short and accused the colonel of being unfit to practise Protestantism. When Mrs Hutchison heard the news, she wrote scathingly that her husband’s grumbling troops were too weak to think logically. Hairstyles, she insisted, were a trifling matter; whatever happened to the idea of judging a man on his courage?

It was a time when ideologies ran deep and tensions ran high, and the Hutchinsons’ hairstyle dilemma reflects the extent to which wartime life had been radicalised. Nevertheless, it seems ironic: the Parliamentarian army had thrown conformity to the King out the window, but conformity (or lack thereof) to the right hairstyle could drive a wedge between companions in arms.

Disorder and Dignity

As we have seen, outfit choices could define a soldier’s ideology. But as the years dragged on, their clothing took on a new role: it enabled them to cling onto their dignity on a brutal battlefield.

The gritty and devastating reality of war led many soldiers to despondency. Among them was Lucius Carey, thirty-three year-old Lord Falkland. In 1643, before his final battle, Carey requested a clean shirt to wear on the battlefield; poignantly, he insisted that if he were to be found dead, it would not be ‘in foul linen’.

Six years after Carey died on the battlefield, it was the turn of King Charles I to request his final outfit. On the morning of his execution on 30th January 1649, it was bitterly cold. Charles, concerned that shivering could be mistaken for cowardice, wore two shirts, including an extra undershirt made of thick knitted silk. In his captivity, clothing was his last card to play: in one sense, as he approached the block and axe, his two shirts protected not only his own dignity but also the reputation of the monarchy.

Twenty-three years before his execution, Charles had worn another famous outfit. At his coronation in 1626, he had opted to wear white satin instead of the traditional purple robes, a symbolic choice that persisted in the memory of his supporters. After his execution, they would remember Charles as the ‘White King’.

For rich and poor alike – for the fiery young and the cynical old – clothing acquired a crucial role during the turbulent years of the English Civil War. After all, in an era of disorder, the wardrobe remained a little island of familiarity: one thing at least that could be controlled.

Mary McVicker is a freelance writer and proofreader based in the Scottish Borders. She has a particular interest in the English Civil War and is currently working on a children’s book.

Published: 22nd August 2024.