The Guinea Pig Club was a social and support club for airmen who had sustained catastrophic burn injuries during World War Two and who had been operated on by RAF consultant plastic surgeon, Sir Archibald McIndoe, in his specialist burns unit at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead.

“It has been described as the most exclusive Club in the world, but the entrance fee is something most men would not care to pay and the conditions of membership are arduous in the extreme”. – Sir Archibald McIndoe

This Guinea Pig Club was formed in July 1941, around a bottle of sherry on a hospital ward, when a group of six airmen who were recovering under the supervision of Sir Archibald McIndoe decided to make their recovery camaraderie official. The club began with 39 members, including McIndoe and other hospital staff, as a social and drinking club, but by the end of the war it had grown to 649 members, and had become a mainstay of the airmen’s recovery process. Many of the injured airmen would undergo several operations, and remain in recovery sometimes for years; the club acted as an informal kind of group therapy and support. The requirements of membership to The Guinea Pig Club were simple: you had to be an allied airman who had suffered burn injuries in the war and had undergone at least two operations by McIndoe at the Queen Victoria Hospital.

Statue of plastic surgeon, Sir Archibald McIndoe, East Grinstead with Sackville College in background. Image made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Statue of plastic surgeon, Sir Archibald McIndoe, East Grinstead with Sackville College in background. Image made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Archibald McIndoe was born in Dunedin in New Zealand on 4th May 1900. He studied at the University of Otago before moving to London. In 1938 he became consultant plastic surgeon for the RAF, then in 1939 he was transferred to a cottage hospital, The Queen Victoria, in East Grinstead. This was to become the Centre for Plastic and Jaw Surgery, and the birth place of the Guinea Pig Club. McIndoe was so revered and respected by the patients he treated that he was known affectionately as ‘Maestro’ and ‘The Boss’.

During the Battle of Britain, it was mainly RAF fighter pilots who sustained the type of burns severe enough to end up in McIndoe’s care.

At this time in 1940 they made up most of the membership of the club, but by the end of the war, most members were from RAF bomber command. However, injured pilots from all over the allied forces would come to be treated by McIndoe, so effective and revolutionary were his methods. There were members from New Zealand, Australia, Canada, America, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Russia.

Before around 1936, anyone suffering a catastrophic burn injury would have simply died. The medical profession at the time just didn’t know how to deal with these injuries. Luckily, this all changed under Sir Archibald. He realised that the airmen who were burned but crashed into the sea, tended to heal better than those that had crashed on land. With this in mind, he began giving patients saline baths, with excellent results. He used techniques never before tried, and when asked in 1938 how he had known how to help a patient with burnt away eyelids, when there was nothing on such injuries in the text books, he replied, “I looked down at the burned boy and god came down my right arm.” – Sir Archibald McIndoe.

It was the experimental nature of McIndoe’s treatment that led the men to christen themselves, ‘The Guinea Pig Club’. They also referred to themselves as ‘McIndoe’s Guinea Pigs’ and ‘McIndoe’s Army’, and they even had their own song, sung to the tune of Aurelia by Samuel Sebastian Wesley.

“We are McIndoe’s army,

We are his Guinea Pigs.

With dermatomes and pedicles,

Glass eyes, false teeth and wigs.

And when we get our discharge,

We’ll shout with all our might:

“Per ardua ad astra”

We’d rather drink than fight

John Hunter runs the gas works,

Ross Tilley wields the knife.

And if they are not careful

They’ll have your flaming life.

So, Guinea Pigs, stand steady,

For all your surgeon’s calls:

And if their hands aren’t steady,

They’ll whip off both your ears

We’ve had some mad Australians,

Some French, some Czechs, some Poles.

We’ve even had some Yankees,

God bless their precious souls.

While as for the Canadians – Ah!

That’s a different thing.

They couldn’t stand our accent

And built a separate Wing.

We are McIndoe’s army…”

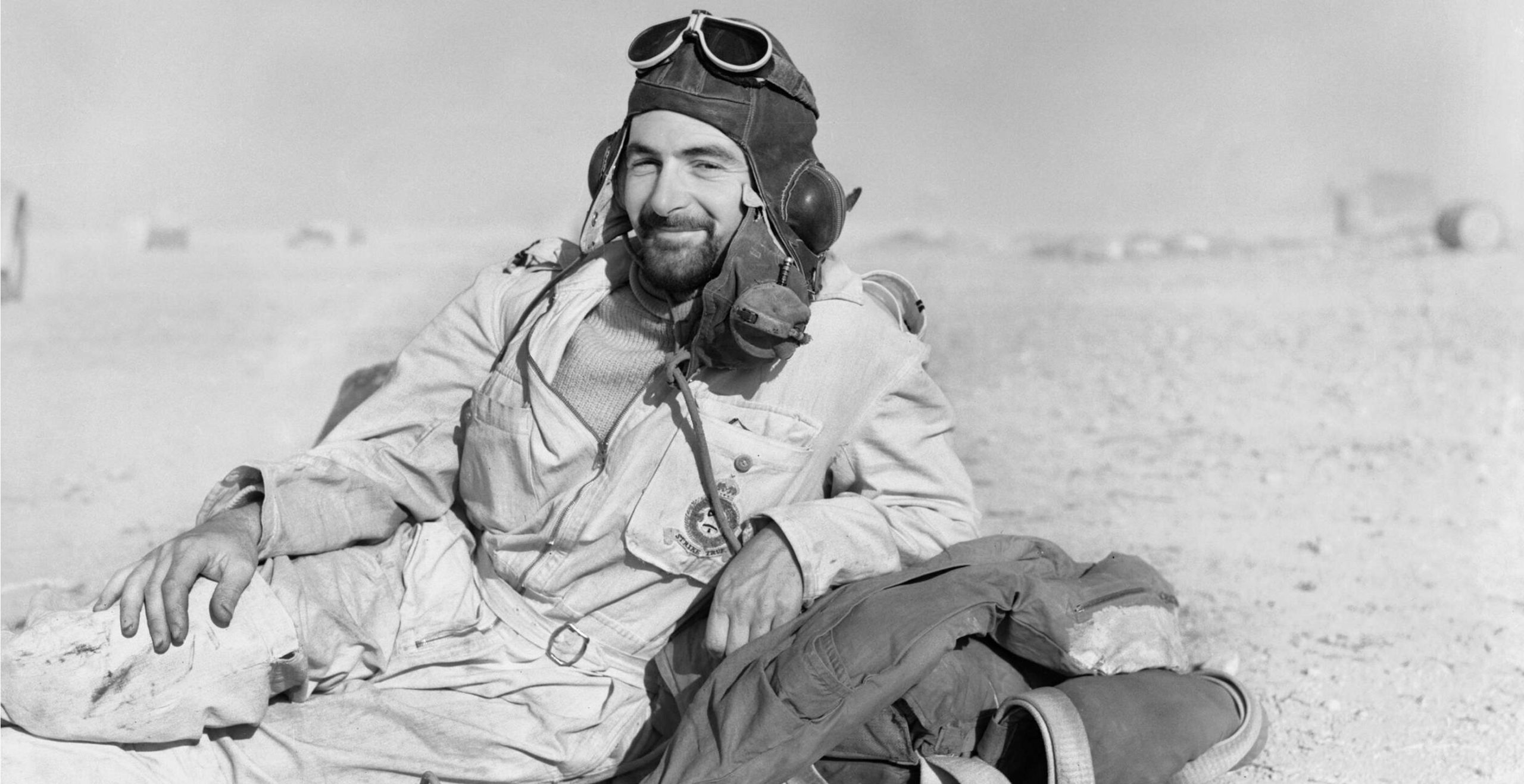

“Per Ardua ad Astra” is the motto of the RAF and means “through adversity to the stars” and nowhere is this more profoundly represented than in the members of The Guinea Pig Club. Amazingly, some of them made such a comprehensive recovery that they returned to flying duty, determined to see out the war as active combatants.

These men, some as young as nineteen or twenty survived injuries that only ten years earlier would have undoubtedly killed them. However, for McIndoe it wasn’t just about physically healing these men, it was about giving them back their purpose and pride, about making them feel accepted back into society. He implored the people and businesses of East Grinstead to welcome these airmen with open arms and to treat them with the respect they deserved.

“Yes, the war is over for most people, but not quite for these men, and the job we’ve got to do is to make them feel like they are back on the map spiritually although they mayn’t be physically.” – Sir Archibald McIndoe

The town rose to the challenge admirably. They formed such a bond with the airmen of The Guinea Pig Club, that even now East Grinstead is affectionately known as “The Town That Didn’t Stare.”

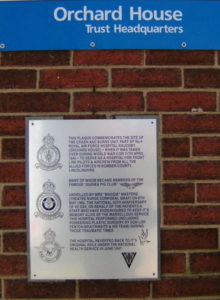

Guinea Pig Club Plaque, South Rauceby, Lincs by Vivien Hughes

Guinea Pig Club Plaque, South Rauceby, Lincs by Vivien Hughes

McIndoe’s approach to healing these men was holistic. There was beer allowed on the wards, socialising was actively encouraged, and McIndoe intentionally hired experienced and attractive nurses who wouldn’t flinch at the sometimes horrendous sights that would confront them on the wards.

Between 1939 and 1945 there were over four and a half thousand allied airmen who had burn injuries from the war and of those injuries, 80% were what became known as ‘airmen’s burns’. These were deep tissue burns to the hands and face. Missing noses, lips and eyelids was common, as too was the curling in of the fingers into claws or fists. Wearing gloves hadn’t been mandatory for airmen before this this point, but when such injuries started to occur so frequently they were quickly mandated.

These injuries were also most prevalent during the Battle of Britain. The weather had been particularly good at that time, between July – October 1940, and cockpits were hot and sweaty. As a result, many pilots didn’t wear gloves or goggles. If they were shot down or crashed and the cockpit was engulfed by flame, the results were catastrophic. This was exacerbated by the introduction of new aircraft and more powerful fuel, which led to new and horrific injuries. It has been estimated that during some of these flash fires, sometimes caused by incendiary bullets hitting fuel tanks, temperatures could reach a sudden 3000 degrees centigrade inside the aircraft. This would of course, cause unimaginable damage to any exposed skin.

The fear of fire was well known amongst aircrew at the time. They called the fuel they carried ‘hell brew’ and ‘orange death’. It was universally acknowledged as the worst way to perish, and some aircrew were known to leap from burning planes even without parachutes, to avoid that which they all most dreaded. However, when the worst did happen, they had Archibald McIndoe to help them.

“Whose Surgeon’s fingers gave me back my pilot’s hands” – Geoffrey Page (Guinea Pig)

The Club was meant to last the duration of the war, but the bond between these airmen was so strong that it lasted until 2007, when the club had their final reunion. The last president of the club was HRH Prince Phillip Duke of Edinburgh.

Historian Emily Mayhew has said that it is hard to overstate the significance of Archibald McIndoe and what he did for these men. It is undeniable that he left behind an amazing legacy both for the airmen that he saved and in “The Town That Didn’t Stare.” The Blond McIndoe Centre was opened in 1961 at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, known today as the Blonde McIndoe Research Foundation. This foundation continues to do pioneering research into burns and would healing and reconstructive surgery today thanks to McIndoe and his Guinea Pigs.

By Terry MacEwen, Freelance Writer.

Published: 24th May, 2022.