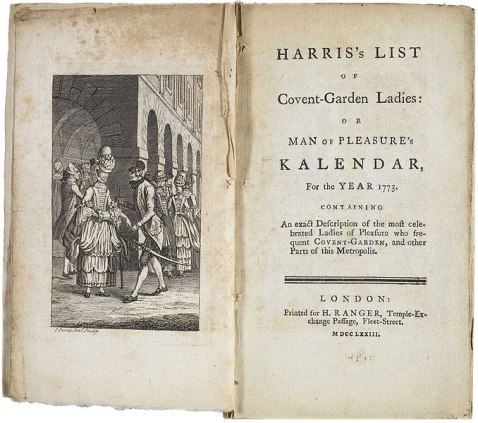

Bawdy books and pamphlets had been around since the Restoration. Five issues of the ‘Wandering Whore’ had been published between 1660 and 1661, and ‘A Catalogue of Jilts, Cracks & Prostitutes, Nightwalkers, Whores, She-Friends, Kind Women and Other of the Linnen-Lifting Tribe’ was published in 1691.

However ‘Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies’, an annual directory of prostitutes working in London published from 1757 to 1795, was a Georgian bestseller. A small guide book, it was printed and published each year at Christmas and sold for two shillings and sixpence. Incredibly, a report from 1791 estimates that Harris’s List sold at least 8,000 copies a year! It would appear that this little book was essential reading for gentlemen visiting London for pleasure.

London at this time was a city rife with prostitution, and Covent Garden was one of the most affected areas. More than two thirds of London’s “disorderly houses” or ‘houses of ill repute’ (brothels) were to be found around Covent Garden and the Strand.

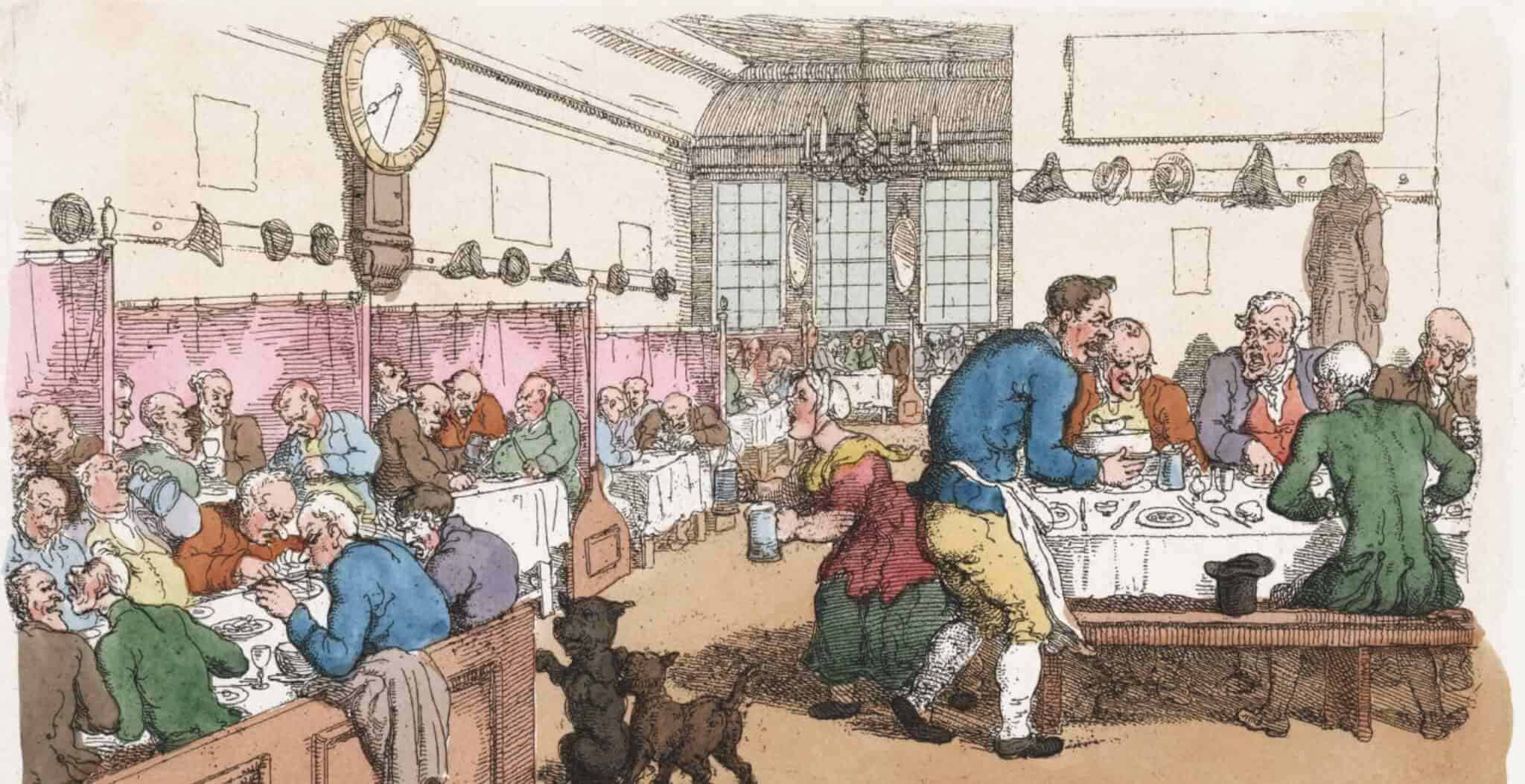

This was a crowded, vibrant and lively part of London, filled with people from all walks of life: artists, actors, writers, musicians, criminals, prostitutes and street walkers. Bounded by the two main theatres, Covent Garden and Drury Lane, the Shakespeare’s Head Tavern and the Bedford Coffee House were two of the most popular haunts. Here you would find not only streetwalkers but also famous courtesans and ‘actresses’ rubbing shoulders with aristocrats and common criminals.

The original author of Harris’s List was probably the poet and drunk, Samuel Derrick. He is said to have become friendly with Jack Harris (John Harrison), head waiter at the Shakespeare’s Head Tavern and self-proclaimed ‘Pimp-General of All England’. Jack Harris had compiled a list of over 400 of the most well known prostitutes in London. The original Harris’s List was based on this document.

Harris’s List named around 150 prostitutes who worked around Covent Garden and described each in lurid details. Information was included on where to find them, what they looked like, their general health, a bit about their past, their ‘specialities’ and their prices, which ranged from five shillings to five pounds. Most descriptions were complimentary; some, however, were anything but. The 1773 listing for Miss Berry describes her as “almost rotten, and her breath cadaverous“.

A common complaint regarding street prostitution was the foul language used, however Harris’s List doesn’t always seem to find this unattractive: Mrs Russell was admired for her “vulgarity more than any thing else, she being extremely expert at uncommon oaths”.

Below is an example of an entry from the 1761 Harris’s List:

“Jenny Nelson, St Martins Lane.

A jolly smart wench, a good companion at table; but particularly joyous in bed; there are few whores to be found so generous as she is, often restoring the money when she likes her man; but she drinks damnably, and is then too apt to be saucy.”

As well as the prostitutes, some of their clients were also named in the Lists. Amongst others, these included King George IV, author James Boswell and the statesman Robert Walpole.

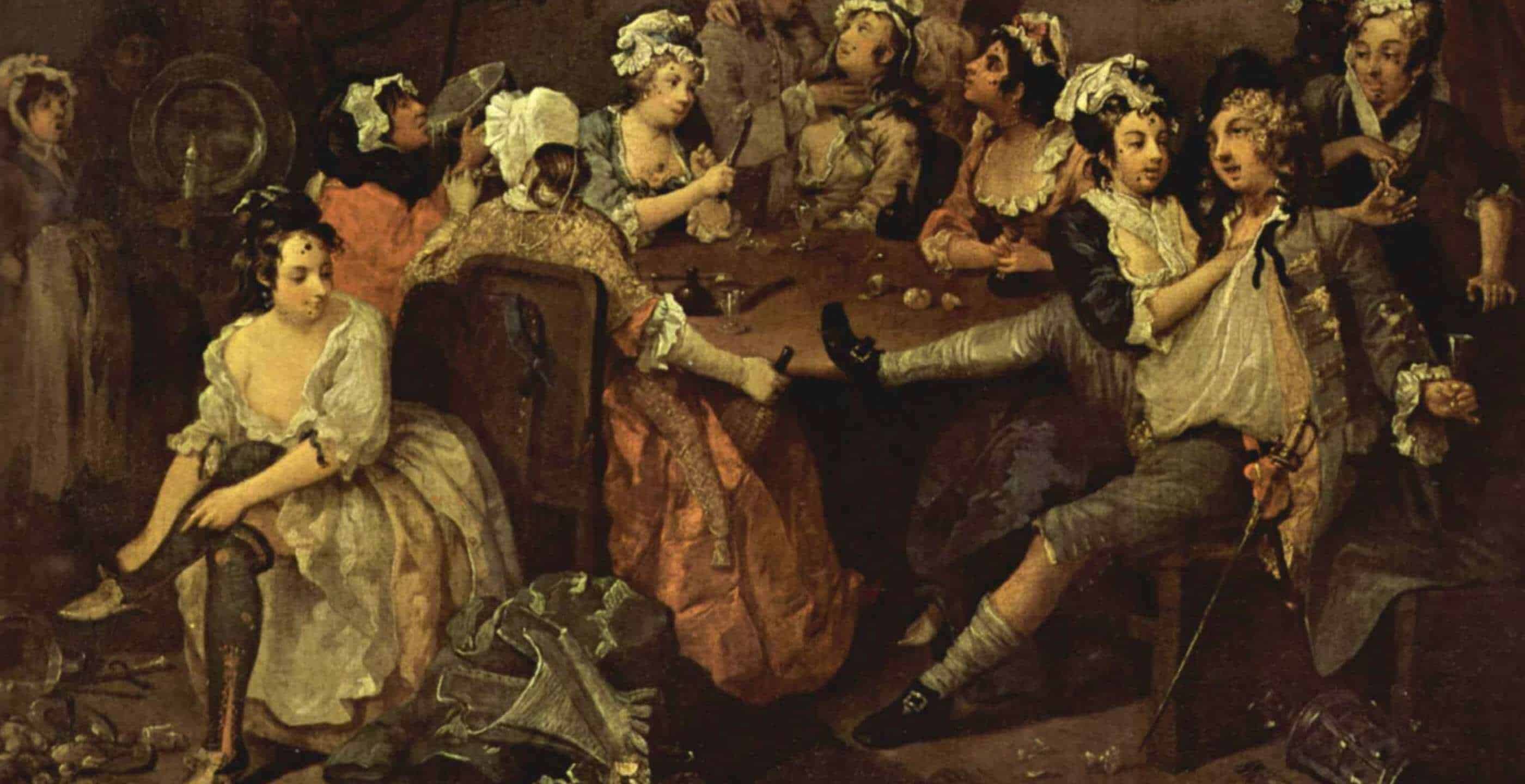

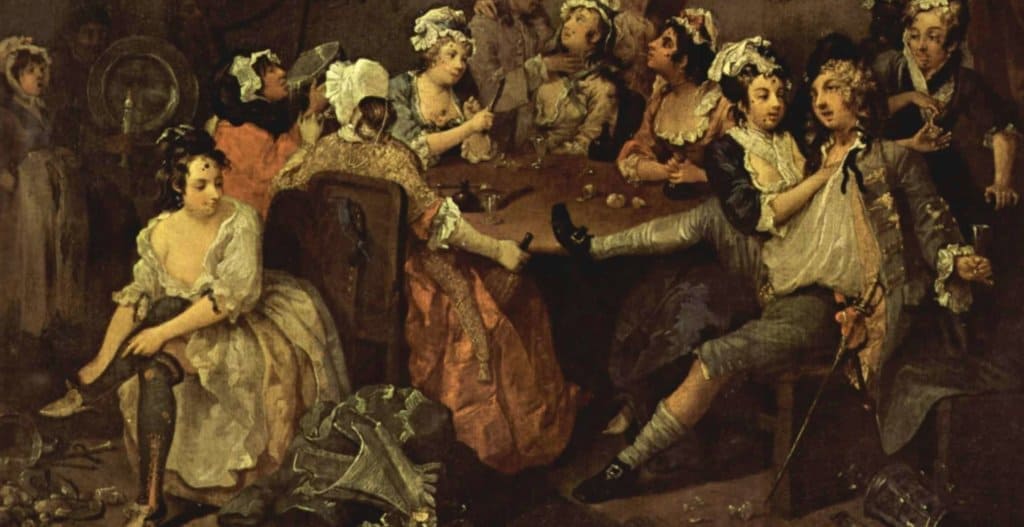

Such was the scale of prostitution in London, in 1731/2 the artist William Hogarth created ‘A Harlot’s Progress’, a satirical and moralistic series of six paintings and engravings telling the story of a young woman arriving in London from the country and becoming a prostitute.

Attitudes towards prostitution hardened towards the end of the 18th century. Public opinion began to turn against London’s sex trade, with prostitution now considered indecent and immoral.

The last Harris’s List was published in 1795. Today some historians consider Harris’s List purely as erotica, however at the time it would appear to have been an indispensable guide book for men seeking pleasure in London.

Published: 3rd June 2015.