Think of animals at the Tower of London and the famous ravens are the creatures that come to mind. These intelligent and emblematic birds have been residents of the tower for many centuries under the care of the official Ravenmaster, and the current holder of the post has amassed a huge Facebook following through sharing daily updates of their antics.

Until the 19th century, however, the ravens had serious competition in the form of a whole menagerie of exotic animals, many of which were gifts to English kings from other rulers. Exchanging animals was all part of international diplomacy for medieval monarchs.

Exotic animals had been imported into Britain since Roman times. Claudius is credited with bringing an elephant as part of his invasion force, though this is the subject of much debate. The wild beasts for the animal fights that were popular in Rome were also imported into Britain, to “entertain” bored troops on a night out at the local amphitheatre after a tour of duty.

The credit for the first true menageries, however, goes to the Norman and Plantagenet kings. At Woodstock, Henry I established a park within a secure wall to keep the foreign animals he acquired from continental and Scandinavian rulers. These are said to have included lions, leopards, lynxes, a camel and, most famously, a porcupine. Part menagerie, part hunting domain, part love-nest, Woodstock was the country retreat of choice for Henries I and II.

King John both relocated the existing menagerie to the Tower and expanded it by importing three cratefuls of new exotic animals. The official date of the start of the Tower Menagerie is usually taken as 1235 however, with the gift of three lions (described as leopards) from Emperor Frederick II to Henry III. The beasts were symbolic of the three lions on the crest of the king of England.

The animals, though, were real enough and needed care and feeding. More creatures quickly followed and the budget came under the scrutiny of the kingly eye. London’s sheriffs soon found themselves requested (in that regal way that leaves no room for argument) to pay for the feeding of the royal beasts.

Among the many marvels the visitor to London could experience in the 1250s was the “pale” or “white” bear presented to Henry III by King Haakon of Norway. Possibly jaded by all the big cats, the London population seems to have really taken to the new arrival.

Sculpture by Kendra Haste at the Tower of London. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Attribution: Jonathan Cardy

Sculpture by Kendra Haste at the Tower of London. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Attribution: Jonathan Cardy

While it’s not certain that the white bear was a polar bear, it seems the most likely conclusion. Norse travellers had encountered the bears and written about them in sagas, and Haakon was an expansionist king who had brought Iceland and Greenland under Norwegian control.

Not only were the sheriffs to provide sustenance for the bear at the lowly rate of 4 sous a day (hardly enough for the bear necessities), they also had to suffer the indignity of one of Henry’s off-hand sets of instructions when he decided that the bear should be capable of providing for itself.

The sheriffs were told to create a stout muzzle and chain so that the animal’s Norwegian handler could control the bear when leading him out of the tower down to the River Thames. Also, a long rope to control the bear when he was in the water having a wash and fishing for himself. They also provided warm clothing for the handler.

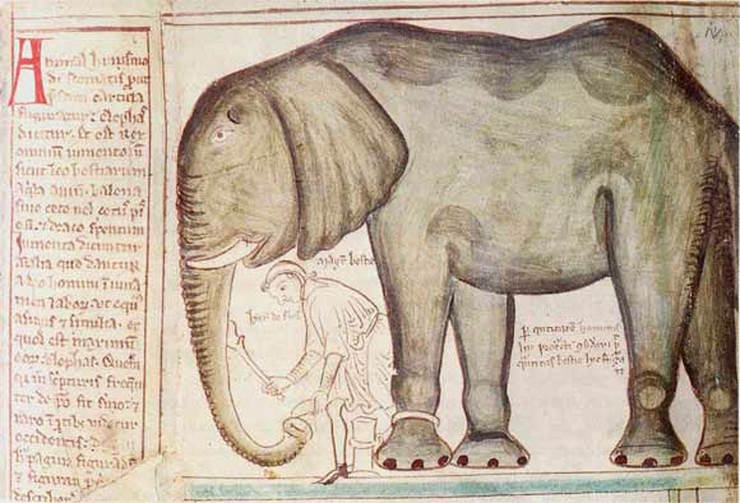

It was undoubtedly worth it for the show. Visitors and locals alike must have gathered to see the daily sight of a polar bear dipping and swimming in the Thames. In fact, it was only the arrival of the elephant in 1255 that upstaged the polar bear.

It’s a pity we don’t know whether the bear had a name, or how he and his handler got on. It seems there must have been a bond there for the handler to be able to put on and take off the muzzle. Bears were important in Norse myth and legend, and so the white bear was as royal and symbolic a gift as the leopards or lions.

Many bears of various types would inhabit the menagerie at the Tower in later years, including one who is said to have made a single ghostly return that caused the death of a Tower guardsman. However, the remarkable image of the “pale” bear swimming and fishing in the Thames is one that had lasting impact on London’s population and visitors from elsewhere in the kingdom, as well as those from overseas.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.