As the festive season draws near, the familiar sound of Christmas music begins to make its annual appearance. Whilst our favourite Christmas songs often have jolly lyrics and modern upbeat tempos, their origins stem back much further!

With the spread of Christianity across Europe from the fourth century onwards, the first carols appeared with Franciscan friars.

The origins of ‘carols’ come from a ring dance which was performed to accompanying music, whereby the dancers (or carollers) would dance around and sing verses. The word itself stems from the French word carole which means ring dance and first appears in the English language in 1300.

By the end of the century, the word had entered the vernacular and was used by the most famous poet and author of the day, Geoffrey Chaucer in his famous literary creation, ‘The Canterbury Tales’.

In the fifteenth century, carol had evolved to mean just a song rather than a reference to the ring dance.

These songs were more commonly defined by their structure, rather than their subject matter which could include religious matters referencing Christ’s life, saints or holy days. Aside from a more theological theme, carols also included politics and worldly matters referencing love, socialising or even vices such as drinking!

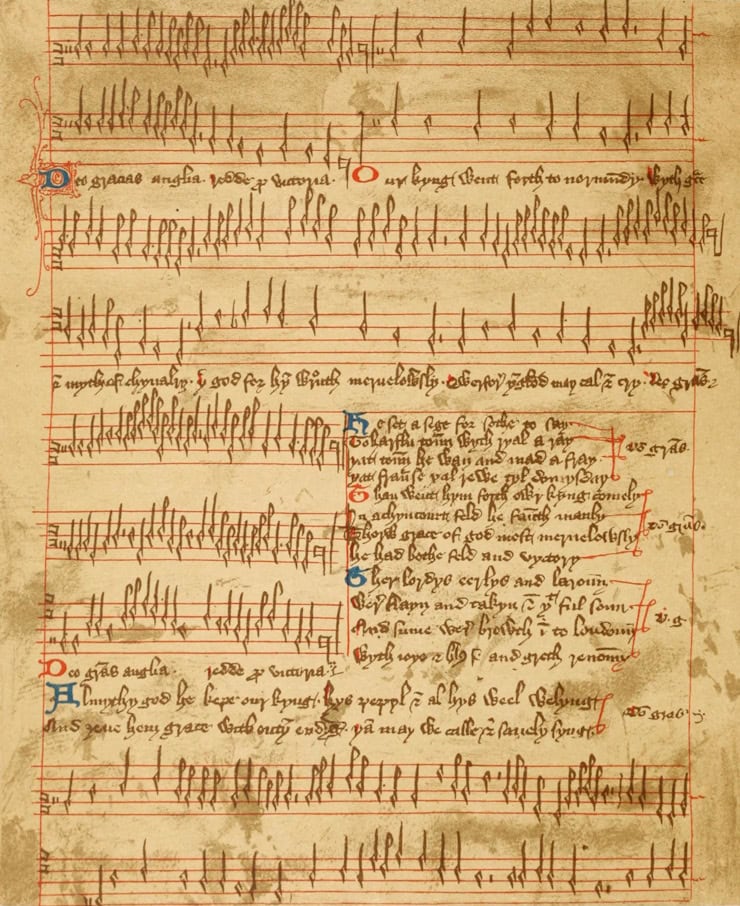

One such example includes the ‘Agincourt Carol’ which was composed in the early fifteenth century and recounts of the Battle of Agincourt fought in 1415, celebrating the English victory secured by King Henry V and his men.

Each stanza of the carol ends with the phrase ‘Deo gratias’ meaning Thanks be to God and ‘Deo gratias Anglia redde pro victoria! Which translates as Give thanks, England, to God for victory!

These emotive and strongly patriotic lyrics are more akin to a national anthem than a carol, however such language would have not been unusual during this period. Moreover, the inclusion of Latin was commonplace because all church services at the time were still conducted in Latin so even non-speakers would have been aware of the phrases.

The carol itself forms part of a larger collection known as the Trinity Carol Roll which originates from East Anglia and is now housed in the Wren Library of Trinity College, Cambridge.

The Trinity Carol Roll is a manuscript dating back to the fifteenth century which contains the lyrics of thirteen English carols. Originally compiled after 1415, many of the texts are composed in Middle English or alternating between Latin and Middle English which is known as macaronic. Such documentation was not unusual as parchment scrolls were common during the Middle Ages as a cheaper alternative to bound books.

Whilst the exact provenance is unknown, what is apparent is that the text was written by someone from the region, in a southern Norfolk dialect and was handwritten by the scribe using the Cursiva Anglicana script which became the normal script for English literary texts from this period.

Meanwhile, the subject matter of these recorded carols is predominantly about Christmas with six of them about the Nativity, two about saints and three about the Virgin Mary.

The titles include:

Hail mary ful of grace (Hail Mary full of grace)

Nowel nowel (Noel, Noel)

Alma redemptoris mater (Loving Mother of our Saviour)

Now may we syngyn (Now may we sing)

Be mery be mery (Be merry be merry)

Nowel syng we now (Nowell sing we now)

Deo gratias Anglia (England give thanks to God) (a. k. Agincourt Carol)

Now make we merthe (Now make we mirth)

Abyde I hope (Abide I hope)

Qwat tydyngis bryngyst yu massager (What tidings bring you messenger?)

Eya martir stephane (Eia [exclamation] martyr Stephen)

Prey for us ye prynce of pees (Pray for us ye prince of peace)

Ther is no rose of swych vertu (There is no rose of such virtue)

The carols which emerged during this period had primarily theological, moral and Christmas themed messages, however there was a greater array of subject matter included and in some cases the lyrics proved to be risqué and lewd in tone.

Throughout the medieval period, the popularity and ubiquity of carols continued to grow.

Whilst it was not a new phenomenon to have song accompany celebration, from the time of the Anglo-Saxons onwards, Christmas-time music and song was being composed in monasteries across the country as recorded by the Venerable Bede.

Whilst religious venues such as monasteries were logical places for such music to be composed for Christmas, carols were in the Middle Ages more often sung at home in festive celebration or whilst wassailing.

From the medieval carols which survive today, around half of them, almost 250, are Christmas in theme and message. So much so, that by the end of the fifteenth century, the term ‘Christmas carol’ was already being used to refer to the festive songs.

What differs considerably from the Christmas traditions of today, is the presence of carols before 24th December. In the medieval times, the period known as Advent was a sombre occasion based on reflection, spirituality and abstinence.

The Christmas carols of this period would only have been sung on Christmas Eve and continued until the feast of the Epiphany on 6th January. During this time, many holy days had their own individual carol to mark it. such as St Stephen’s Day.

By the turn of the sixteenth century, all Christmas related songs were beginning to be referred to as carols.The proliferation of carols however soon came under threat as the advent of the Reformation changed the religious landscape of the country forever.

The Reformation, instigated by King Henry VIII, was a drawn out and politically fraught affair which saw the predominantly Catholic Britain embark on a conversion to Protestantism. The impact of this process was felt in all spheres of life and affected politics, economics and culture. Whilst the massive changes introduced impacted traditional practises, surprisingly carols survived these seismic shifts. Owing in large part to the fact that carols were often sung in the home environment, they remained an aspect of celebration.

Moreover, prominent Anglican figures such as the bishop Lancelot Andrewes strongly advocated the singing of Christmas carols, particularly when partaking in festive celebrations at home. Only a select few extreme religious followers would have taken umbrage at singing carols and refused to participate.

However, in 1647, the puritan parliament effectively banned Christmas, including all the usual festive traditions associated with the period. Such draconian measures even extended to the home and private celebrations.

In 1660 the Christmas ban was removed with the Restoration and thus traditions which had been suppressed, could quietly and slowly emerge out of the fog of the puritan measures. Still reeling from the effects of the ban, carols would not regain their popularity until the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, the tradition of singing carols remained the preserve of the home whilst religious settings dealt with the fallout of the new ideas and practises of the Reformation.

Thus, the humble Christmas carol managed to survive the onslaught of Protestant reforms where many other traditions had failed. Carols were sung in hearty convivial atmospheres and form part of wassailing which reflected the value of Christmas carols, not only for individual families but the wider community.

Whilst Christmas carol singing traditions were maintained at home, by the eighteenth century the only Christmas carol officially sanctioned by the Church of England was ‘While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks’, which became an official Anglican carol in 1782.

In the meantime, other popular carols were composed such as ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’, written by Charles Wesley. In the following century, more carols emerged which crossed the religious schism. In 1841, ‘O Come, All Ye Faithful’ was translated into English.

The era which is most associated with Christmas and had the most notable impact on solidifying many Christmas traditions we are familiar with today was the Victorian era.

In a reinvention of Christmas, aided and abetted by the German influence of Prince Albert, the introduction of Christmas trees, crackers and puddings became a mainstay. Likewise, the Christmas carol too formed an important part of celebrations.

Some of the most popular carols which are still sung today originate from this period including, ‘Away in a Manger’, ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’ and ‘We Three Kings’.

In 1880, an important development occurred when Bishop EW Benson of the Truro Cathedral held a service on the night of Christmas Eve called ‘Nine Lessons with Carols’. In the newly founded cathedral, local parishioners had requested to sing carols in church and thus the service was breaking new ground, as such singing had been reserved for the middle class Victorian gentry who had choirs visit their homes for private performances. This particular service helped to open up the tradition and break down the social boundaries which restricted much of Victorian society.

In recognition of this momentous occasion, in 1918 a Christmas service was held at the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge with the name, ‘A Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols’.

Marking the end of the First World War, the service not only recognised the significance of its Victorian predecessor but was used as a moment of remembrance, thus reflecting the power of singing carols in the community.

Today, Christmas carols are an enjoyable and less formal part of festive celebrations, whether sung at a school nativity, in church or simply at home, they have become a mainstay of the Christmas period and reflect both tradition and a long enduring British history of social, religious and political legacies.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 13th December 2024.