On still summer evenings, the balloon can often be seen drifting through calm skies above Britain. Many of us may even have experienced this gentle form of flight in all its soaring splendour. But how did UK manufacturing methods assist and shape the development of this truly ‘uplifting’ form of aerial exploration?

From home-built early incarnations involving silk flowers, encyclopaedia editors and craftsman collaborations through to substituted cinemas and the onset of formalized factory production, balloon builders have helped pioneer many aeronautical advancements.

(To clarify some terminology: contemporary examples are usually of the ‘hot air’ variety, the contents of their fabric ‘envelopes’ maintained at temperature by a propane burner, unlike ‘gas balloons’ which are airtight structures filled with a gas such as helium to create lighter-than-air lift.)

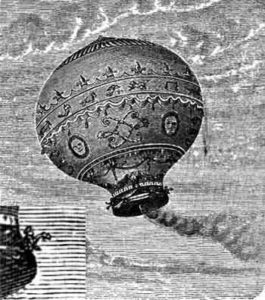

Mongolfier brothers’ hot air balloon, 1783

Mongolfier brothers’ hot air balloon, 1783

The Montgolfier brothers – paper-manufacturers by trade – had made the first successful manned flight in Paris in 1783, following earlier animal experiments (infamously sending a cock, a duck and a sheep aloft). ‘Balloonmania’ had taken off.

In 1783, the first successful British balloon experiment was conducted from Cheapside, London, when Italian entrepreneur Count Francesco Zambeaccari collaborated with an artificial flower maker to construct five small unmanned balloons. These silk-sewing skills were scaled up the following year, when a substantially larger ‘envelope’ was exhibited in Cooper’s Hall, Bristol, for three days, to great public interest. Spectators could pay an extra 2s 6d to ‘see the method and process of filling the balloon with inflammable air’.

Lunardi’s balloon exhibited at the Pantheon, Oxford Street, 1784

Lunardi’s balloon exhibited at the Pantheon, Oxford Street, 1784

Meanwhile, the editor of the ‘Encyclopaedia Britannia’ – James Tyler – had read of the Montgolfier brothers’ success, and in 1784 subsequently built his own ‘Edinburgh Fire Balloon’. This sailcloth contraption would earn him the accolade of the first manned UK flight, although it was the Italian Vincenzo Lunardi who was to ignite public attention with the first flight over England. Taking off in front of a substantial crowd, Lunardi’s 24 mile journey earned him fame and fortune, with St Paul’s Cathedral allegedly increasing its entry price for spectators clamouring for a rooftop view. The same year, John Sheldon – leading anatomist, pioneering surgeon and aviation enthusiast– commissioned an umbrella-maker in the Strand to build him a balloon.

Continuing to draw upon the capital’s wealth of craftsmanship, London aeronaut and manufacturer James Deeker was called upon to build the balloon that would become the first to successfully cross the English Channel, a milestone met in 1785. Another record would be set by aeronaut Charles Green the following year when, in 1786, the ‘Royal Vauxhall Balloon’ would set a world distance record for manned flight – 480 miles – that would remain unsurpassed for eight decades. This behemoth of a balloon was constructed by Sopers of Spitalfields, employing over 2,000 yards of raw silk at a total cost of £2,100 (well over £100,000 in today’s currency).

Charles Green and his Channel-crossing balloon

Charles Green and his Channel-crossing balloon

As ballooning grew in popularity, individual construction projects were joined by more formalized factory production. The UK boasted two major manufacturers: the Short and the Spencer Brothers. The latter – based in Highbury, London – were a trio of balloonists whose father, Edward Spencer, was a trusted assistant of the aforementioned Charles Green.

Meanwhile, after starting their business in Hove, Sussex, the Short Brothers made the move to railway arches 75 and 81 in Battersea, London, alongside an adjacent inflation field. The company proved popular and were commissioned by Charles Royce (later to found Rolls-Royce) to build his 78,500 cu ft. entry for the 1906 Gordon Bennett balloon race. The Short Brothers were also the official aeronautical engineers for the prestigious London-based Aero Club, founded in 1901.

It was not only the civilian market contributing to the booming balloon-building business. Military experiments at Aldershot, Hampshire led the War Office to create a dedicated Balloon Section in 1890. Despite problems of practicality, the balloon was invaluable for airborne observation opportunities. The ‘School of Ballooning’ initially began at Woolwich before moving to the School of Military Engineering at Chatham in 1882. In 1890, the school relocated again to Aldershot under a dedicated division of the Royal Engineers, building balloons to deploy to the Boer War. Finally, the newly-named ‘Balloon Factory’ moved to Farnborough, although the premises ultimately turned its attention to ‘heavier-than-air’ flight from 1913 onwards.

Military ‘School of Ballooning’ at Aldershot, 1890s

Military ‘School of Ballooning’ at Aldershot, 1890s

However, despite the advent of the aeroplane (the Wright Brothers made the first successful ‘heavier-than-air’ flight in 1903), demand for observational military balloons increased significantly with the outbreak of the First World War. In 1917, to assist with demand, an impromptu factory was created at Bohemia Picture Palace in Finchley, North London. This erstwhile cinema sported high ceilings, a grand staircase and an external courtyard garden, all of which provided ample space for balloon construction.

Despite the balloon being redundant in regards to contemporary military applications after the Great War, it had by no means fallen out of favour as a fun way to fly. Designs remained relatively unchanged until the mid-20th century, when American inventor Ed Yost – the ‘father of modern ballooning’ – developed some significant technological advancements, including the introduction of onboard burners fueled by propane tanks.

After his successful first ‘free’ flight in 1960, Scottish aviation enthusiast Don Cameron – and his colleagues at the Bristol gliding club – read of the success in National Geographic Magazine. Over 12 months, they designed and built their own balloon – the ‘Bristol Belle’ – which first flew on 9th July 1967 from RAF Weston-on-the-Green, Oxford, under the guidance of Wing Commander Gerry Turnbull. The first ‘modern’ balloon in Western Europe had proved successful: 20th century British ballooning had been born. Three years later, the Bristol Belle flew from the deck of HMS Ark Royal, carrying mail ashore to Malta.

The Bristol Belle, 1960, Bristol. © Julian Hensey

The Bristol Belle, 1960, Bristol. © Julian Hensey

Inspired by his success, Don Cameron would establish Cameron Balloons in 1971 in Bristol. Production commenced in the basement of his house before moving to an old church, finally progressing to its current factory premises in Bedminster. Alongside ‘standard’ hot-air balloon shapes, Cameron are world-famous for their technologically challenging and visually stunning ‘special-shape’ balloons: custom designs ranging from the Disney castle to giant whales, a Harley-Davidson motorbike, various flying foods and even a rendition of Pixar’s ‘Up’ balloon. Other Cameron-constructed craft have been instrumental in several world records, including the Breitling Orbiter, which completed the first ever circumnavigation of the globe by balloon.

Thankfully, 21st century examples benefit from decades of technological refinement and increased safety standards. The ‘home-build’ is still technically an option, although unlike earlier ‘do-it-yourself’ incarnations, thankfully requires regulatory checks from the UK Civil Aviation Authority. Meanwhile, commercially available envelopes continue to inspire and excite pilots and passengers alike – the latest links in a long line of British balloon-building craftsmanship that certainly shows no signs of slowing.

By Charlotte Bailey. I am a writer and editor based in Bristol, England, with a passion for all things aviation-related.

Published: March 30, 2021.