For thousands of years, British history has rested beneath England’s opulent valleys and shallow marshes. Epochs in time lay amidst the communities that spread across this vast and fascinating country. Nestled in the county of Devon is the quaint little town of Honiton, not far from the south coast of England. Honiton made its mark in British history for creating some of the most beautiful material brought to popularity during the Victorian era.

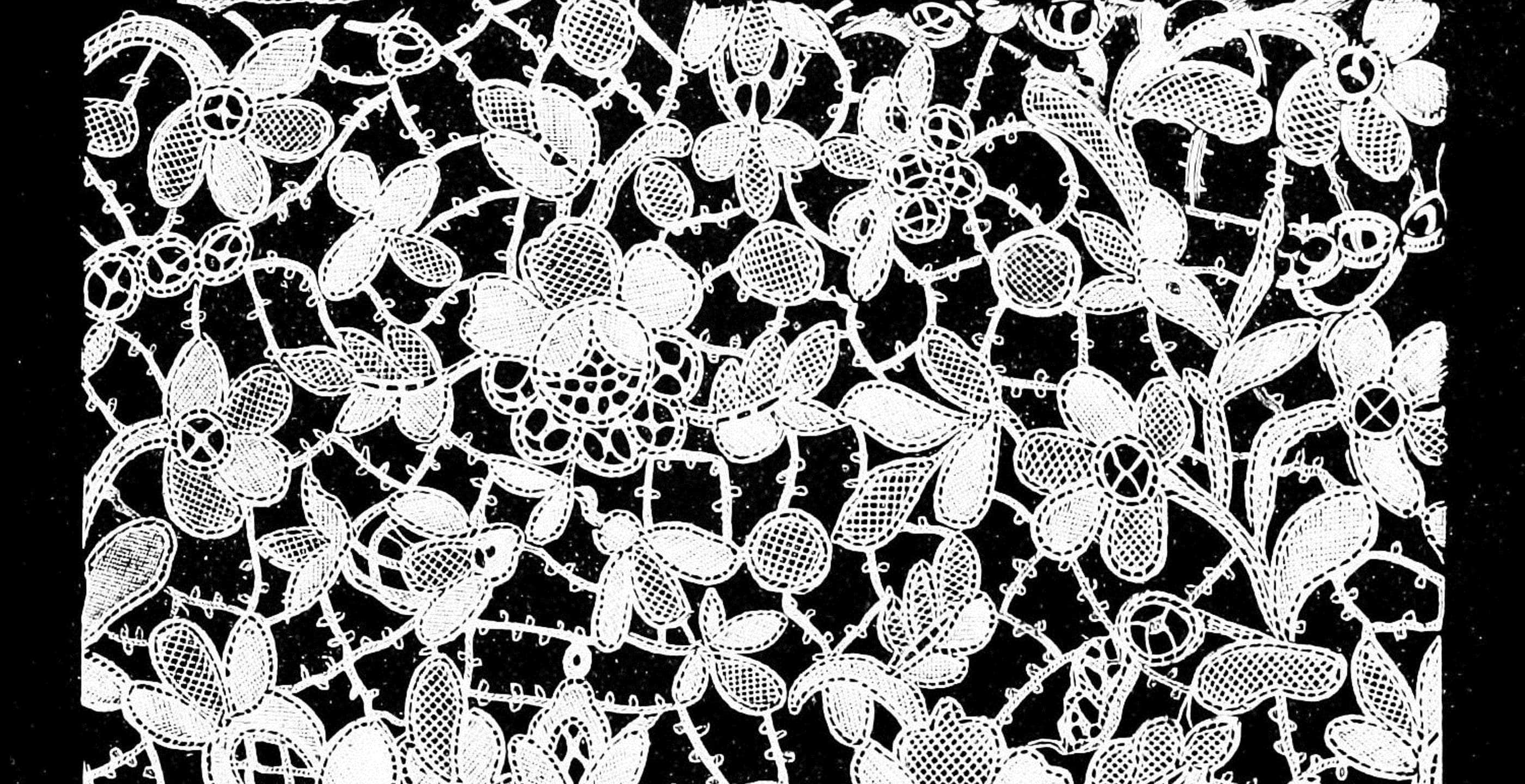

The picturesque landscape decorated with stunning botanical design provided the perfect setting for Honiton lace makers. One of the main characteristics of Honiton lace is the sprig applique that is influenced by the Devon countryside. The history of the Honiton style dates back to the sixteenth century. According to ‘The Lace Book’ written by N. Hudson Moore, bobbin lace was introduced into England by Dutch refugees somewhere about 1568. The earliest mention of the lace is found in a pamphlet titled ‘View of Devon’ in 1620 that mentions ‘bone lace much in request, being made at Honiton and Bradnich’.

Although Honiton lace was well established during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, its true popularity transpired during the Victorian era. The appeal for romance and beauty is well acknowledged during this period but there was also interest in the imperfect. In a document written by Elaine Freedgood titled ‘Fine Fingers’, Freedgood mentions how handmade goods were quite sought after. “In the nineteenth century, handmade items were known and valued for a new-fangled virtue: irregularity (…) as that which produces the “real beauty” of “true” art objects”. Victorian Britain was enamoured with the unique and authentic, which was evidently found in the Honiton craftsmanship.

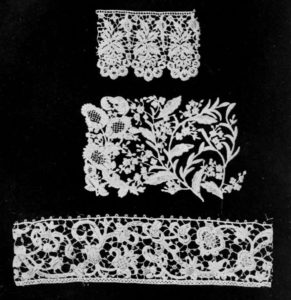

The true climactic point for the Honiton lace popularity was through its royal influence. Queen Victoria’s wedding dress was quoted to have taken over three months and four hundred workers to make. Freedgood remarks that the lace was revitalized when Queen Victoria wed Prince Albert in a dress deeply trimmed with Honiton lace.

Victoria’s influence did not finish with her wedding dress; her presence in lace on several occasions brought much popularity. In an article written by Geoff Spenceley titled ‘The Lace Associations: Philanthropic Movements To Preserve The Production Of Hand-Made Lace In Late Victorian And Edwardian England’, three hundred workers gathered in Honiton to celebrate the Queen’s Birthday Jubilee and constructed a special flounce to mark the occasion.

Spenceley also mentioned “it was well known that orders soon followed an announcement that Honiton lace had been worn in the drawing room”. Queen Victoria was not the only royal to promote the beautiful fabric: Queen Alexandra was also interested in the small town’s aptitude for lace making and made efforts to promote British handiwork. According to Spenceley, “The coronation of Edward VII had produced something of a revival and Queen Alexandra’s request that all ladies wear goods of British manufacture at the Coronation brought many valuable orders”. The royal participation in purchasing and wearing handmade lace from Honiton helped equally with its popularity and economy in British society.

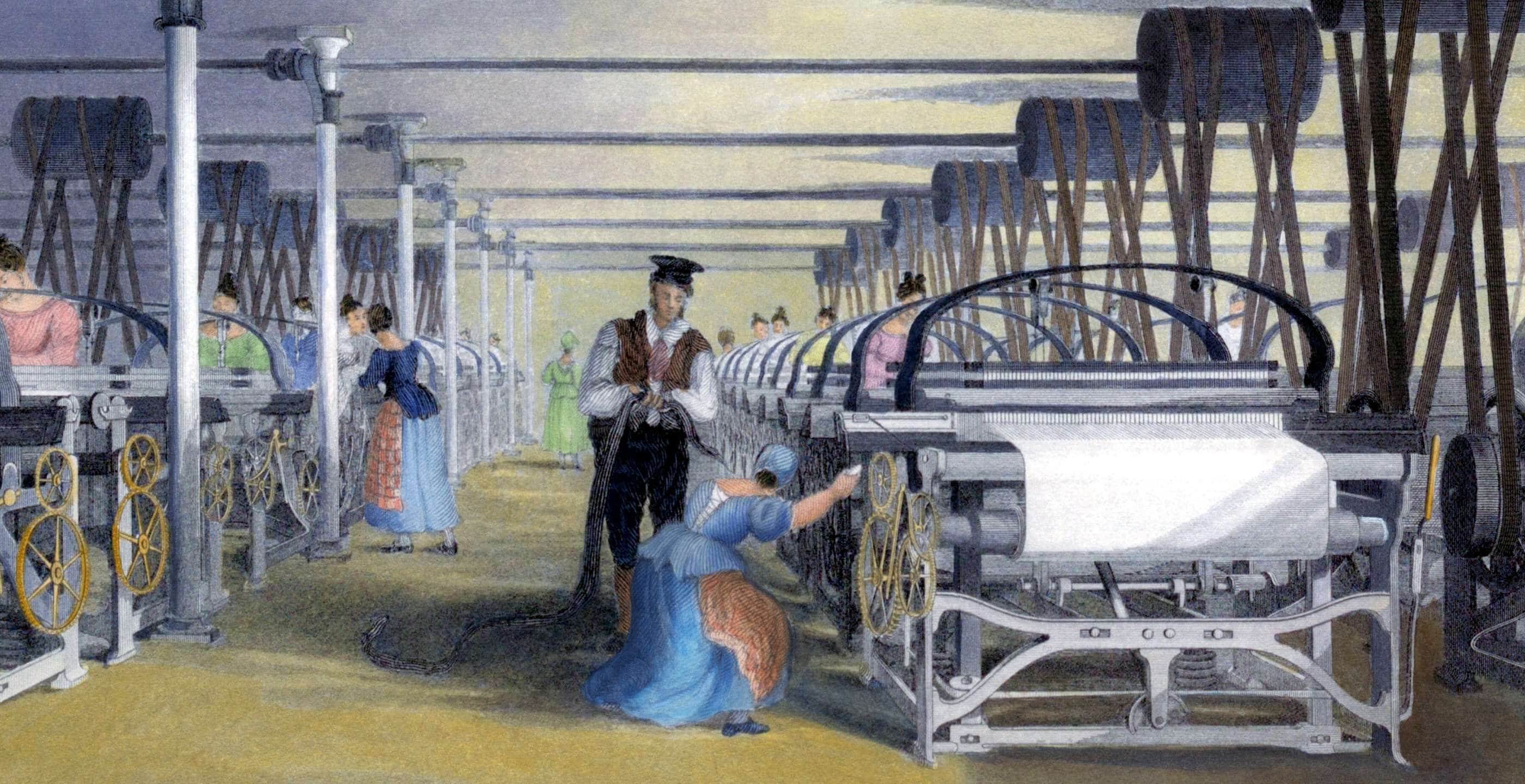

The admiration for handmade lace was well received right up till the late nineteenth century when it later suffered from a fading diminution. Machine made goods were becoming the way of the future and quickly impacted small businesses such as the ones found in Honiton. Shortly after, handmade lace had a new chance with popularity by the founding of Lace Associations, whose mandate was to preserve the traditional methods. Spenceley mentions how the Lace Associations revived the nostalgic and empathetic feelings towards past house workers; “The Associations existed largely on voluntary effort and, to a degree, on charitable funds. Local experiences seem to have given many organizers a heartfelt desire to help poor pillow lace makers out of their plight”. Right up until the early twentieth century the Lace Associations greatly helped the preservation of handmade fabrics. According to Spenceley it was quite apparent the differences between handmade and machine, “A whole world of difference between fabric produced artistically in a rustic cottage, with devotion to beauty and form, and a fabric mass-produced”.

The Victorian era has remarkable character with its effort to appreciate the romance and beauty found within handmade imperfections. The bequest of Honiton craftsmanship was found through the fields of the Devon countryside, the patronage of royal figures that brought it to popularity, and the people who preserved its legacy and historical importance in British culture.

By Brittany Van Dalen. I am a published historian and museum worker from Ontario, Canada. My research and work is centred on Victorian history (primarily British) with emphasis on society and culture.