Mad women have been a subject of scientific curiosity for centuries. But the legitimacy of the diagnoses of Victorian women, in particular, received from the most celebrated psychiatric minds of the time is certainly questionable by today’s standards. Were mad women truly insane? Or were they simply the undesirables of society where incarceration was a convenient option? Let’s take a look.

The idea that women were the weaker sex was a societal norm that has been instilled into British culture for centuries and was hardly exclusive to the Victorian period. However, the Victorian values that discerned the perfect woman were particularly severe, encouraging traits such as intellectual inferiority, passivity and selflessness. Plus, a woman’s primary role was simply to bear children and do the housework, so anyone who deviated from this ideal was often deemed mad as, in society’s eyes, this was the only possible explanation and offered a convenient solution.

The label of madness upon women was often used as a control measure that helped remove those who were non-conformists for ‘the good of society’. It’s therefore unsurprising that surveys at the time reveal that there was often a disproportionate number of female patients in asylums. Some women were of course still diagnosable as mentally ill, even by todays standards, but their diagnosis would likely have been inaccurate. A classic example is that oftentimes epilepsy in women was mistaken for hysteria.

Women under Hysteria, circa 1876-80

Women under Hysteria, circa 1876-80

Causes were often attributed to phenomena, such as religious obsession, physical illness, tragic events, childbirth or marital indiscretion. In some cases, a woman daring to ask for a divorce was grounds to deem her insane and worthy of incarceration. Other reasons for admittance to an insane asylum include laziness, rigorous intellectual study and being in bad company.

But what were these women being admitted for? Well, there were several diseases native to the period, such as melancholy, paralysis and general mania that were attributed to both sexes, but the most significant that pertained only to females was hysteria.

Hysteria was the most well-known and frequently recorded mental illness of women during the Victorian period. Think of the classic image of woman ‘swooning’ and reaching for her smelling salts. Symptoms were hugely broad and included faintness, nervousness, insomnia and convulsions to name a few, but most notably was a tendency to cause trouble. The disease certainly wasn’t exclusive to the Victorian era, as Galen, the father of medicine himself, described it as being predominant in ‘over-passionate women’.

Reports of hysteria became so common because it was a diagnosis often given by default – when doctors couldn’t come up with any other explanation. In fact, in 1859, a physician claimed that over a quarter of women suffered from hysteria.

A set of drawings of a woman with ‘hysteria’ experiencing catalepsy from an 1893 book

A set of drawings of a woman with ‘hysteria’ experiencing catalepsy from an 1893 book

The gendered bias of this malady was down to the fact that doctors believed it was intrinsically linked to a woman’s lack of sexual satisfaction and the womb, meaning men could not suffer from it.

There was a significant amount of hysteria circulating fictional women as much as there were real ones, too. Depictions appeared visually in a number of paintings, including several interpretations of Shakespeare’s Ophelia – a famous character known for her madness and suicide – along with characters in novels of the period, most Notably Bertha Rochester of Jane Eyre and The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins to name a few. The real and imagined presence of female madness plagued society’s hive mind, convincing the great thinkers of the time and lower classes alike that these causes of insanity were in fact legitimate. It also added an innate sexual nature over the illness, displaying these women in a strangely romantic yet vulnerable light.

Jean Martin Charcot demonstrating hysteria

Jean Martin Charcot demonstrating hysteria

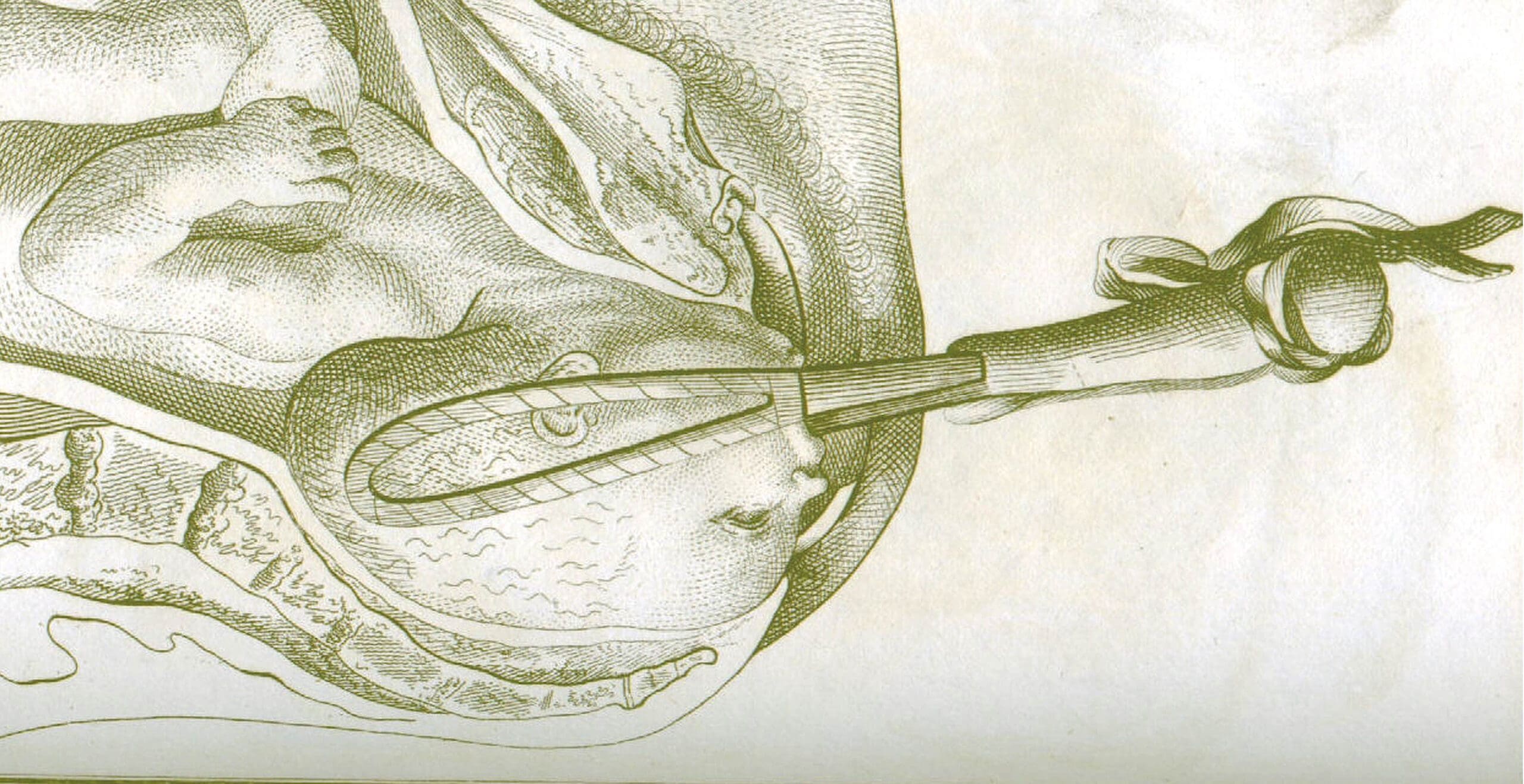

Treatment of hysteria varied inside the walls of asylums, but some of the most common advice earlier in the period was more frequent intercourse for married women, along with massage and vibration, particularly around the pelvis. Clockwork-driven massage machines were frequently used until the 1870s when the first electromechanical vibrator was used in for the first time. Most of these treatments were based on the idea that the womb was responsible, however treatment began to develop when psychologists such as Freud and Charcot began to attribute the illness to the brain, initiating hypnosis as a potential cure.

Other ideas for treatment ranged from bed rest, bland food and avoidance of activities that may over-stimulate the brain, such as reading. However, treatment was broad due to that fact that the diagnosis was widely used when the physician didn’t really understand the cause, so much of it was generalised.

Today, hysteria is no longer recognised as a mental illness, mainly because we now attribute the symptoms to other conditions, such as schizophrenia, anxiety and borderline personality disorder. A greater understanding of mental illness as a whole throughout the 20th century and beyond has allowed society to slowly let go of the idea of the hysterical woman. Post 1930, mention of the disease started to diminish in medical literature and now the term is only used when describing a temporary loss of control over one’s emotions.

Kiera Boyle is a freelance writer with BA(Hons) History and MA Creative Writing. She specialises in women’s and societal history. You can find more of her work at https://kieraeveboyle.wixsite.com/kierawrites