In northeastern England you would be hard-pressed to find a person unaware of the legend of the Lambton Worm, well established in English folklore since the 13th Century. However, when John Lambton became the Governor General of British North America in 1838, probably no more than a handful of residents in fledgling Canada were aware of the Lambton family and its legendary history.

The oral legend of the Worm underwent many revisions over the centuries. Not surprisingly, Sir John, the First Lord of Durham, became the natural hero of the legend as his fame spread throughout County Durham and England’s northeast.

Whisht! lads, haad yor gobs,

An’ aa’ll tell ye aall an aaful story,

Whisht! lads, haad yor gobs,

An’ Aa’ll tel ye ‘boot the worm.

On Sunday morning Lambton went

Afishing in the Wear,

And catched a fish upon his heuk

He thowt leukt vary queer.

But whatnt kind oer fish is it was,

Young Lambton couldn’t tell –

He waddnt fash to carry it hyem,

So he hoyed it in a well.

John George Lambton was born in 1792 to Lady Barbara Frances Villiers and William Henry Lambton, an activist, who helped form and then chaired the Society of Friends of the People. The Friends advocated for reform of Parliament and a more diverse House of Commons.

They believed that any British man should be able to vote in House of Commons elections as long as he wasn’t a convicted criminal or a ‘lunatic.’

Upon his father’s early death from tuberculosis in 1797, five-year-old John became wealthy although too young to manage his holdings. As a gentleman landowner, he would eventually inherit his family’s mansion, Harraton Hall, in County Durham, situated on valuable coal mining land, along with the Lambton Collieries, Dinsdale Park and Low Dinsdale Manor.

Noo Lambton felt inclined to gann

An fight in foreign wars,

He joined a troop of knights that cared

For nowther wounds nor scars,

An off he went to Palestine

Where queer things him befell,

An vary seun forgot aboot

The queer worm in the well.

John – the young Lord of the legend – and his brother were sent to live with Dr. Thomas Beddoes after his mother remarried. Beddoes, a family friend and scientist known for radical liberal ideas, was paramount in John’s education before he left for Eton College in 1804. Taking one of his first independent steps, John left school in 1809 to marry Harriet, illegitimate daughter of the Earl of Cholmondeley. Finding out Harriet was too young and could not get her father’s permission to marry, the dejected John joined the Prince of Wales’s Own 10th Hussars army regiment as a Cornet (Second Lieutenant).

A deployment to Palestine introduced John to bloodshed close-up. Unlike the brave young man in the legend, John decided the army was not to his liking. He resigned his commission in 1811 and returned home. John and Harriet married in 1812 and had three daughters before Harriet died in 1815.

Barely a year later, John married Lady Louisa Grey, an artist, daughter of the 2nd Earl Grey. Five more children resulted – two sons and three daughters.

But thu worm got fat an growed and

Growed, an growed an aaful size.

He’d greet big teeth and a greet big gob

An greet big goggly eyes.

An when at neet he craaled aboot

Ta pick up bits a’news,

If he felt dry upon the road

He sucked a dozen coos.

This fearful worm waad often feed

On calves an lambs and sheep,

An swally little bairns alive

When they laid down to sleep.

An when he’d eaten aa’ll he cud

An he had hed his fill,

He craaled away and lapped his tail

Curled many times roond the hill.

The nuws ov this most aaful worm

An his queer gannins on,

Seun crossed the seas and got the ears

Of brave and bold Sir John.

So hyem he came an catched the beast

An cut him in two halves,

An that seun stopped him eatin bairns

An sheep an lambs and calves.

While John was overseas with the Hussars, the legend of the Lambton Worm had thrived. The strange worm-like fish that young Lambton had caught and hoyed (tossed) down the well had grown. Not only had it escaped the well but in one version of the story wound itself round and round Fatfield Hill (or Penshaw Hill, depending on who is telling the story), eating sheep, sucking milk from cows, and carrying off young bairns (children).

Once released from military duty, young Lord Lambton set about making a name for himself. He was elected to Parliament for County Durham in 1812. He supported a liberal agenda including the removal of ‘political disabilities on Dissenters and Roman Catholics.’ Between 1820 and 1828, John commissioned the building of Lambton Castle around the existing Harraton Hall. Standing on a rise above the town of Chester-le-Street, County Durham, surrounded by parkland, the castle was established as the ancestral seat for the Lambton family.

Subsequently in 1828, John was awarded the peerage title, Baron Durham, of the city of Durham and of Lambton Castle. When Lord Grey, his father-in-law, became Prime Minister in 1830, John Lambton was elevated to the Privy Council as Lord Privy Seal. As Baron Durham, John remained in the Cabinet until 1833, leaving with the bestowed titles Viscount Lambton and Earl of Durham.

George Woodcock wrote in a 1959 article, that the young John Lambton, First Earl of Durham, was “Proud, wayward, immensely rich, with romantic good looks and an explosive temper…one of those natural rebels who turn their rebellious energies to constructive purposes. Both at home and abroad he became a powerful exponent of the early nineteenth-century liberal spirit.”

Appropriately, Lambton was given the nickname, ‘Radical Jack’. When asked what an ‘adequate income’ was for a gentleman, Lambton replied, “a man might jog along comfortably enough on £40,000 a year” (approximately $7,800,000 in Canadian dollars today.) This earned him another moniker, ‘Jog Along Jack.’

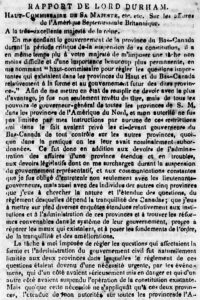

Following a stint as Ambassador to Russia from 1835 to 1837, John Lambton was named Governor General and High Commissioner for British North America by the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne. The Rebellions of 1837 between William Lyon Mackenzie’s Upper Canada (Ontario) and Louis-Joseph Papineau’s Lower Canada (Quebec) had landed many French-Canadian rebels behind bars. Arriving in Quebec, Lambton found the situation dire.

He wrote, “I expected to find a contest between a government and a people: I found two nations warring in the bosom of a single state: I found a struggle, not of principles, but of races; and I perceived that it would be idle to attempt any amelioration of laws or institutions, until we could first succeed in terminating the deadly animosity that now separates the inhabitants of Lower Canada into the hostile divisions of French and English.”

On June 28, 1838 – Queen Victoria’s coronation day — Lambton gave amnesty to all but twenty-four of the French-Canadian rebels. For this the English castigated him, resulting in loss of support from Prime Minister Melbourne and Parliament.

Lambton embarked upon an in-depth study of conditions in Upper and Lower Canada. In Ontario, the western district of Upper Canada, he received a warm welcome. In accordance with an Act of the Parliament of Upper Canada in 1798, the counties of Essex and Kent comprised a huge portion of the western district with Point Edward a central locale. As Lambton approached the welcoming platform in Point Edward, an arch had been set up stretching from one bale of hay to another with a lamb standing in-between. Local residents, fond of the charismatic Lambton, had honored him by symbolizing his family name…a lamb between the bales (tons) of hay. Lambton was duly touched, and reciprocated by giving the name Lambton to the area, leading to the creation of Lambton County years later.

His loss of support in British Parliament, however, prompted Lambton to resign his post. Back in London in 1839 he penned his Report on the Affairs of British North America (The Durham Report). It recommended the union of Upper and Lower Canada, creating the Province of Canada, but responsible government was not established until 1848.

Both sides sparred over representation – whether Canada should have a federal or unitary government. Despite Lambton’s initiative, it took until 1867, well after his death, for a federal state to be established. Included in the new Dominion of Canada were New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with Ontario and Quebec becoming two provinces.

Sir John Lambton… Lord Privy Seal, Earl of Durham, Governor-General of Canada… died on the Isle of Wight in 1840, at age forty-eight, reportedly of tuberculosis like his father before him. His only surviving child, George, succeeded him as Lord Lambton. Louisa, the Countess of Durham, only lived another year, and died in 184l of a “serious cold.” She was forty-four.

Despite the accolades Lord Lambton earned during his short life, his family was saddled with the legacy of the Worm. A darker, more sinister version of the original fable exists which damned nine generations of Lambtons to die unnatural deaths. According to that version, the Worm’s curse would not be defeated unless John killed it, then killed the next living thing he saw.

The legendary John did kill the Worm, cutting it in half. Fearing a member of his family would be the first living thing he saw, the story says he asked his father to send one of the hunting dogs out at the sound of the hunting horn. But his father, relieved that the Worm was dead, forgot to release the dog. Later, John of fable indeed killed the dog, but it was too late to save the family from the curse.

Three generations of Lambtons gave credence to the curse. In 1583, Robert Lambton drowned at Newrig; Colonel William Lambton was killed at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644; and Henry Lambton was killed in his carriage on Lambton Bridge in 1761. And, it is said that Henry’s brother kept a horse whip beside his bed…just in case the Worm should make an appearance.

So now ye knaaa hoo aal thru folks,

On byeth sides o’er the Wear,

Lost lots o’ sheep and lots ‘o sleep

An lived in mortal fear,

So lets hev one te brave Sir John

Tht kept thu bairns frae harm,

Saved coos and calves by makin halves

Of the famous Lambton Worm.

The Lambton Worm, Geordie Version

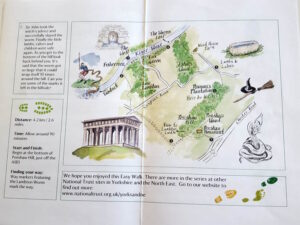

In 1844 a monument was commissioned by residents in the Sunderland area in northeast England to commemorate their favorite son, Lord John Lambton. On Penshaw Hill, between Washington and Houghton-le-Spring, the monument, styled after the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, became a local landmark.

The Marquess of Londonderry donated stone from his quarries in Penshaw to build the monument. “It has afforded me great satisfaction in a very humble manner to aid in recording my admiration of [the Earl of Durham’s] talents and abilities, however I may have differed with him on public or political subjects,” he stated. Many considered the structure a folly, however, Lord Lambton and the monument’s appeal allowed much of the money for construction to be raised by subscription. Citizens donated enthusiastically.

Today, people picnic on the grass and Easter egg hunts are held annually on the hill. The National Trust encourages tourists to traipse the worn paths where the Worm once slithered. Mothers still warn their bairns not to wander too far from home – all because of a young man named John Lambton who skipped church one day to go fishing.

Postscript:

When my mother moved to Lambton County, Ontario in 2017, I was inspired to find the Lambton Worm connection. She grew up within sight of Penshaw Monument and a short walk from the Lambton Estate in England. When I was a child, my mother and grandfather recited the ‘awful story’ of the Lambton Worm in their northeast Geordie accent. Family outings to picnic on the hillside around Penshaw Monument are a treasured memory.

By Beverley Foster Bley.

Published 28th April 2023