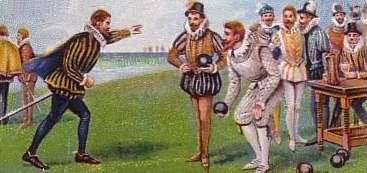

Sir Francis Drake is best known for calmly finishing his game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe as the Spanish Armada sailed up the English Channel. Whether this is a true story or not, the larger-than-life Tudor mariner was famous in his own lifetime for his dangerous voyages and exploits.

Sea captain, explorer, slave trader, privateer and pirate: Drake was all of these and more. To the Spanish he was a pirate (El Draque) but to the English, he was a hero. From the singeing of the King of Spain’s beard – his raid on Cadiz in 1587 – to his voyages around the world ( the first Englishman to do so) Drake was immensely popular.

After his death a legend arose involving a drum, emblazoned with his coat of arms, that had reputedly accompanied him on all his voyages. This was an early European side drum, used on board ship for calls to arms or for entertainment; Drake was fond of music and on his circumnavigation, he took four viol players with him on the voyage. Whilst the drum dates from the 16th century, the coat of arms that decorates it was added in the 17th century.

It is generally believed that Drake’s drum was among the 13 drums rescued from Hawkins’ and Drake’s fatal last voyage to the Caribbean in 1596. Shortly before his death off the coast of Panama in 1596, it is said that he ordered the drum to be taken to Buckland Abbey, his home in Devon. He is said to have vowed on his deathbed that if England were ever in danger and the drum was sounded, he would return to defend his homeland.

Drake’s Drum on display at Buckland Abbey, before it was moved to The Box in Plymouth.

Drake’s Drum on display at Buckland Abbey, before it was moved to The Box in Plymouth.

The drum is also said to mysteriously beat by itself during times of peril. Legend has it that it has been heard to beat at important times in English history:

– when the Mayflower left Plymouth for the New World in 1620

– when Napoleon Bonaparte entered Plymouth harbour as a prisoner aboard the Bellerophon

– in 1914 on the outbreak of World War One

– in 1918 on HMS Royal Oak just before the surrender of the German fleet

– during the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940.

Two British army officers also claimed they heard the drum beating during the Battle of Britain in September 1940. It was also said to have been heard beating quietly in 1982 during the Falklands War and on 7th July 2005 when London was hit by a terrorist attack.

The legend of Drake’s drum fits into the category of ‘king of the mountain’ or ‘sleeping hero’ folklore. These are tales of national heroes ready to awake at times of national need, such as the legend of King Arthur and his knights, sleeping in Avalon waiting to arise when required.

Drake’s role as a protector of England is first mooted in a poem written by Charles Fitz Geffrey only a few months after Drake’s death, ‘Sir Francis Drake, His Honourable Life’s Commendation And His Tragical Death Lamentation’. The last few lines of the poem seem to suggest that he is forever watchful over England:

“The sea no more, heaven then shall be his tomb

Where he a new made star eternally

Shall shine transparent to spectator’s eye

But shall to us a radiant light remain

He who alive to them a dragon was

Shall be a dragon unto them again

For with his death his terror shall not pass

But still amid the air he shall remain

This role continued because England wished it to be so! “

The legend was further reinforced in 1897 with the publication of Sir Henry John Newbolt’s famous poem, ‘Drake’s Drum’, some lines from which are quoted at the head of this article.

Drake’s Drum, arriving at Buckland Abbey from Plymouth City Museum, 1951

Drake’s Drum, arriving at Buckland Abbey from Plymouth City Museum, 1951

The drum has been in the ownership of Drake’s descendants since the late 16th century. It was first mentioned at Buckland Abbey in an account of traveller George Lipscomb in 1799 and it was at Buckland in 1938 when it was rescued from the fire that beset the Abbey. It was acquired by Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery from the family in the 1950s and returned to Buckland Abbey on loan. The drum has now been moved to The Box, in Plymouth. Buckland Abbey is in the care of the National Trust.

Published: 11th February 2020.