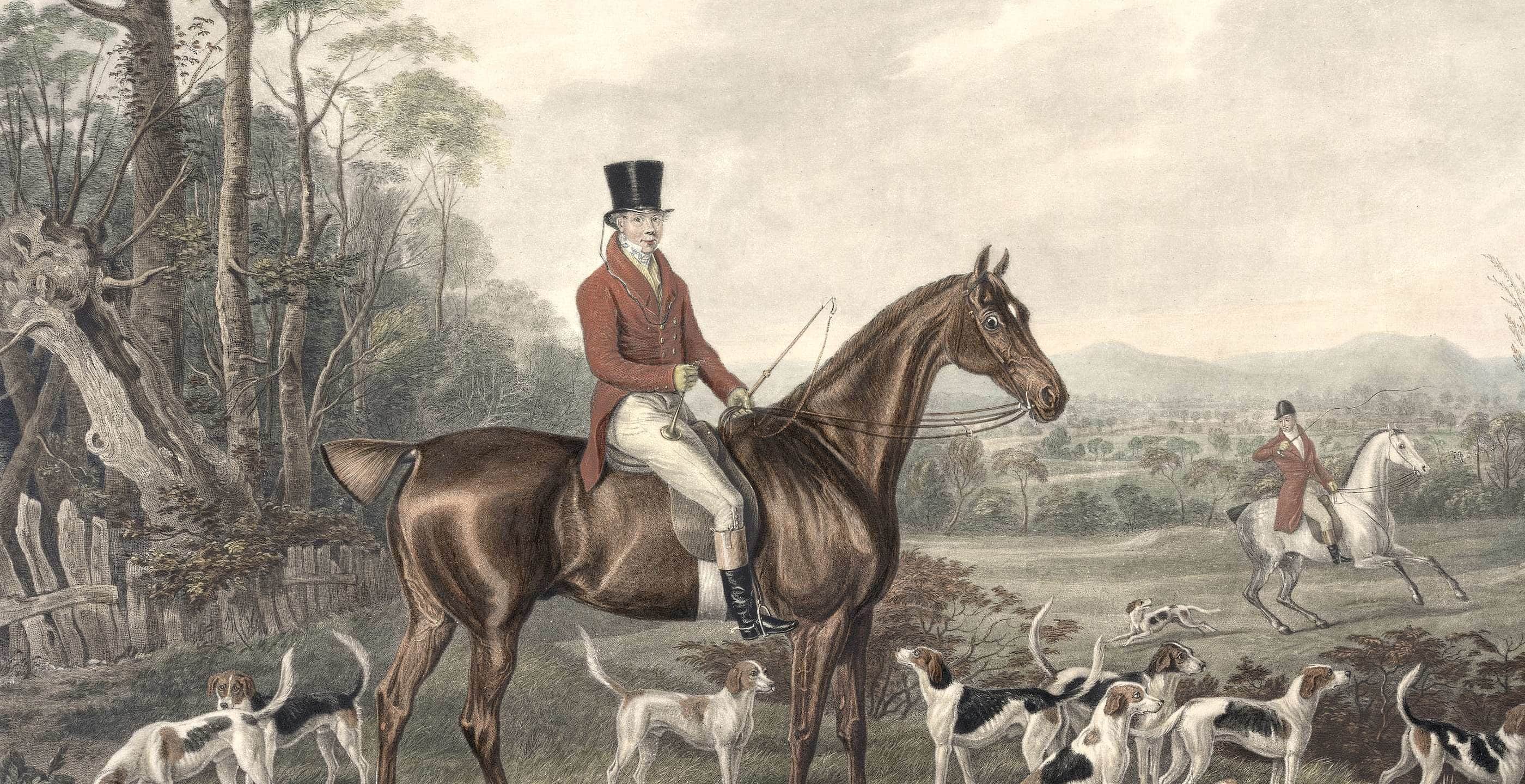

The archetypal wicked squire turns up in many a racy yarn by writers such as Catherine Cookson. The heyday of these hard-riding, hard-drinking hunting characters was the 18th and 19th centuries and their exploits also captured the imagination of novelists such as Charles Dickens, Robert Smith Surtees, and Somerville and Ross, the authors of ‘The Irish RM’.

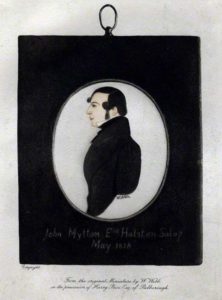

However, no fictional squire could match the real-life character Squire Jack Mytton, who was born near Shrewsbury in 1796. Mytton’s life and adventures were chronicled by “Nimrod”, the pen name of Charles James Apperley, who became something of a celebrity himself in sporting journalism. Like Mytton, Nimrod shunned a “respectable” career, choosing instead the hunting field and writing for the Sporting Magazine.

It was in fact a great career move, which even had product tie-ins – a coach was named for Nimrod, as were breeches and a newspaper. Nimrod was a risk-taker himself, though not in the same league as his friend, Squire Jack Mytton.

A phrase often turns up in connection with characters such as both Nimrod and Mytton: “neck or nothing”. It indicates the type of person who will risk all, whether at gambling or in the pursuit of some high octane activity that brings an adrenaline rush.

Nimrod was there to witness some of Mytton’s outrageous risks. In fact, Nimrod had to point out that however unbelievable some of the tales were, he had witnessed many of them himself and wasn’t even revealing them all: “…yet I might hazard an imputation on my veracity were I to recount ail the extraordinary deeds of this most extraordinary man, in various situations with hounds.”

One of the most famous stories involved Mytton riding into his own drawing room on a bear which he kept at home. He was dressed in full hunting outfit, including spurs with which he pricked the animal, which promptly and understandably turned round and bit his leg right through.

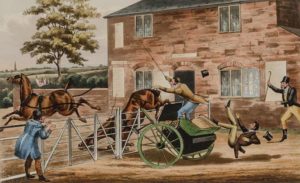

Another time, while trying out a new horse in tandem (one horse in front of another, which requires great skill) Mytton asked the horse dealer if he thought the horse was “a good timber-jumper”, a requisite for horses that would hunt across country. The bemused dealer didn’t know. “Then we’ll try him,” said Mytton, making the unfortunate horse jump a turnpike gate while still attached, leaving the second horse and demolished vehicle on the far side of the gate.

Once he scared the living daylights out of a passenger in his gig (a fast, light, horse-drawn vehicle) by asking him if he had ever been “much hurt, by being upset in a gig?” On learning that his companion had never been in a gig that had overturned, Mytton promptly arranged the experience for him on the spot. This was typical of the often cruel practical jokes he seemed to enjoy so much, such as dressing as a highwayman to hold up two of his acquaintances.

Mytton seems to have had the constitution of an ox, since he frequently went hunting in the thinnest of clothing in freezing cold weather. On one occasion he is said to have crossed over a frozen surface stark naked in pursuit of ducks he wanted to shoot.

Money was no object and when it ran out he could always borrow more. Nimrod describes him as “a perfect stranger to the science of economy.” He was master of two packs of foxhounds and also kept a number of racehorses in training, up to 15 or 20 at a time, with broodmares and youngstock to support as well. When advised that he should attend Oxford University, he said he would do so if he could “read nothing but the ‘Racing Calendar’ and the ‘Stud Book’”.

Mytton had an exceptionally bad money habit, in fact. His biographer lists very precisely that he had 152 pairs of breeches and trousers, with coats and waistcoats to go with them. He spent lavishly on alcohol and imported game in huge numbers for hunting.

When advised that if he could keep his spending to £6,000 per year he would not have to lose his Shrewsbury estate, he responded “You may tell Longueville to keep his advice to himself, for I would not give a damn to live on six thousand a year.” As an MP for Shrewsbury he lasted just half an hour in the House of Commons.

It is not hard to imagine the effect that a lifestyle like that of Squire Mytton, the archetypal Regency rake, would have on immediate family. His biographer Nimrod comments that “Turning from his more public life as a sportsman to his domestic relations as a husband and a father, a delicate hand is certainly required when speaking of Mr. Mytton’s conduct towards his two wives” (the first died young after giving birth to the only child of the marriage. His second marriage produced five children).

Nimrod continues revealingly: “…the evil must at once be laid bare to our view. I reluctantly admit, that Mr. Mytton’s conduct in the marriage state is in great part indefensible, and can only be palliated by a due allowance, which must not be denied him, for that sort of insane delirium under which he so frequently laboured…”

Just as in many accounts of modern celebrity marriage breakdowns, Mytton was accused of all kinds of abusive behaviour. Charged with throwing his first wife’s lapdog onto the fire, Nimrod responds that “he merely took it up in his arms, threw it halfway up to the drawing-room ceiling, and caught it, without injury.”

Accused of also attempting to drown his first wife, Nimrod replies “Nonsense; he was never mad enough to do that. He merely, one very hot day, pushed her into the shallow of his lake at Halston, a little over her shoes.”

Not surprisingly, Mytton is one of the characters in Edith Sitwell’s ‘English Eccentrics: A gallery of weird and wonderful men and women’ where he is described as a “poor driven drunken ghost…This half-mad hunting hunted creature.” By his late 30s he was dying, a dissipated wreck, in debtors’ prison: “a tottering old-young man, bloated by drink, – there was a body as well as a mind in ruins…” as Nimrod described him.

Mytton and his like were celebrities, the 19th century equivalent of bad boy rock stars, always in the public eye for the trouble they caused. Roistering their way through unbelievable fortunes, they often ended destitute and alone, seemingly drawn to self-destruction that also damaged so many of the people close to them. Yet they could charm as well, even as they damned their own souls to perdition. As Nimrod summed it up: “His cardinal virtue was benevolence of heart; his besetting sin a destroying spirit, not amenable to any counsel, and an apparent contempt for all moral restraint.”

Modern day horse riders, walkers and cyclists can now enjoy 100 miles of peaceful countryside following the route of the Jack Mytton Way in Shropshire without fear of a squire dressed as a highwayman holding them up along the way!

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.