In the mid-eighteenth century the effects of gin-drinking on English society makes the use of drugs today seem almost benign.

Gin started out as a medicine – it was thought it could be a cure for gout and indigestion, but most attractive of all, it was cheap.

In the 1730’s notices could be seen all over London. The message was short and to the point:

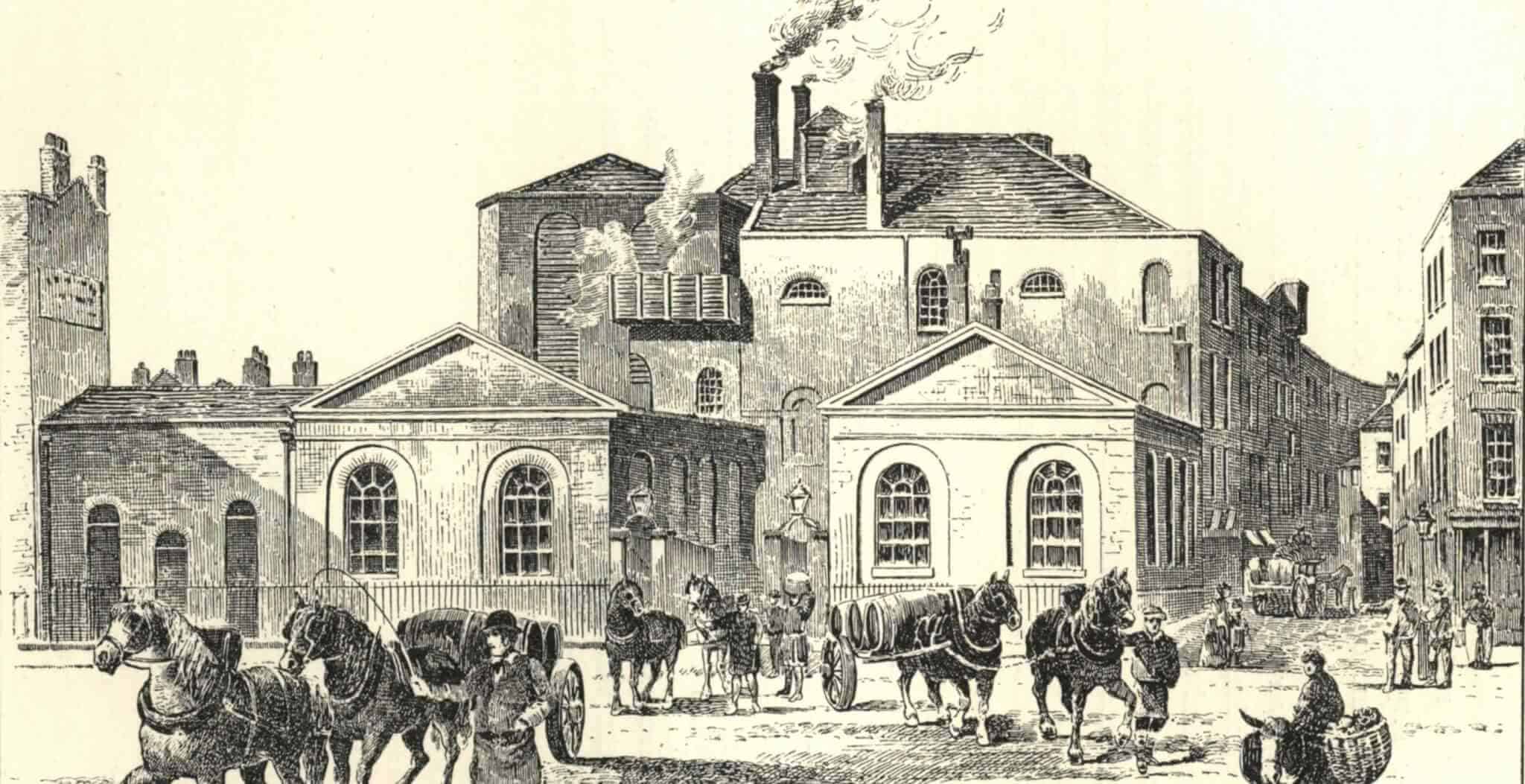

In London alone, there were more than 7,000 ‘dram shops’, and 10 million gallons of gin were being distilled annually in the capital.

Gin was hawked by barbers, pedlars, and grocers and even sold on market-stalls.

Gin had become the poor man’s drink as it was cheap, and some workers were given gin as part of their wages. Duty paid on gin was 2 pence a gallon, as opposed to 4 shillings and nine pence on strong beer.

The average person could not afford French wines or brandy, so gin took over as the cheapest, and most easily obtained, strong liquor.

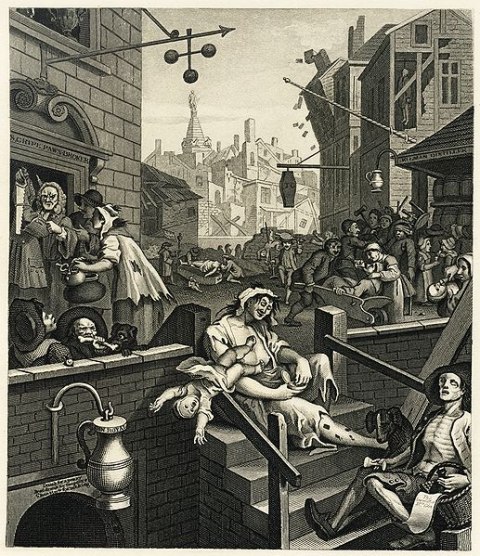

Gin rendered men impotent, and women sterile, and was a major reason why the birth rate in London at this time was exceeded by the death rate.

The government of the day became alarmed when it was found that the average Londoner drank 14 gallons of spirit each year!

The government decided that the tax must be raised on gin, but this put many reputable sellers out of business, and made way for the ‘bootleggers’ who sold their wares under such fancy names as Cuckold’s Comfort, Ladies Delight and Knock Me Down.

Overnight, gin sales went underground! Dealers, pushers and runners sold their illegal ‘hooch’ in what became a Black Market.

Much of the gin was drunk by women: consequently children were neglected, daughters were sold into prostitution, and wet nurses gave gin to babies to quieten them. This worked provided they were given a large enough dose!

People would do anything to get gin…a cattle drover sold his eleven-year-old daughter to a trader for a gallon of gin, and a coachman pawned his wife for a quart bottle.

Gin was the opium of the people, it led them to the debtors’ prison or the gallows, ruined them, drove them to madness, suicide and death, but it kept them warm in winter, and allayed the terrible hunger pangs of the poorest.

In 1736 a Gin Act was passed which forbade anyone to sell ‘Distilled spirituous liquor’ without first taking out a licence costing £50.

On the last night, as the last gallons of gin were sold off cheaply by the retailers who could not afford the duty, more alcohol was drunk than ever before or since.

The authorities believed there would be trouble the following day but nothing happened. The mob lay insensible in the streets, too drunk to know or care.

In the seven years following 1736, only three £50 licences were taken out, yet the gallons of gin kept coming.

The thirst for gin appeared insatiable. People sold their furnishings and even their homes to get money to buy their favourite tipple.

The horror of the situation in London was portrayed in a print by Hogarth called ‘Gin Lane’. This shows a drunken woman with ulcerated legs, taking snuff as her baby falls into the gin-vault below. Henry Fielding, author of the book ‘Tom Jones’, also delivered a pamphlet to the government stating his protest against the perpetual drunkenness of the Londoners.

Once again the government was forced into action. A new ‘Gin Act’ was passed which raised the duty on drink and forbade the distillers, grocers, chandlers, jails and workhouses from selling gin.

Gin was never again quite so much of a scourge and consumption fell dramatically through the rest of the eighteenth century.

In 1830 the Duke of Wellington‘s administration passed the Sale of Beer Act, which removed all taxes on beer, and permitted anyone to open a Beer Shop on payment of a two-guinea fee.

This Bill virtually ended the traffic in gin smuggling.

By the end of 1830 there were 24,000 beer shops in England and Wales, and six years later there were 46,000 and 56,000 Public Houses.

Britain has witnessed a growth in the popularity of gin over the past few years, but happily it is nowhere near as popular as it was in history!