WOMEN’S football was high on the national agenda when England won the European Championship in July 2022. The triumph of the ‘Lionesses’ was celebrated throughout the country and seen as a watershed moment, specifically for women’s sport and, in general, for equal rights.

As Chloe Kelly raced around the Wembley pitch, pulling off her top in a wild celebration after grabbing the winning goal against Germany she might have shouted: “Three cheers for Nettie J Honeyball!”

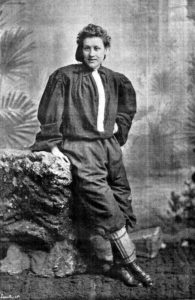

In 1894 Nettie founded the British Ladies Football Club – the first of its kind, although women had played previously in public exhibition games. Forming two teams to play each other, their debut in north London on March 23 1895 attracted over 10,000 spectators, mostly men. Riding high on that success, they toured Britain, featuring in over 100 games in the following two years, provoking the wrath of the male Establishment whose criticism ranged from playful jokes about their lack of ability, to full-on broadsides about women needing to ‘know their place’.

As one outraged newspaper columnist put it: ‘They play in knickers and blouses. They allow their calves of their legs to be seen and wear caps and football boots! What next?’

Well, sir, 127 years later, Chloe Kelly tugged off her shirt, revealing her sports bra, and, instantly, as 90000 fans inside Wembley and millions of TV viewers shouted and danced in jubilation, it became an iconic image of women’s achievements and ambitions. Sadly, that wasn’t the case with ‘Team Nettie’ who were often caricatured as ‘silly girls’ dressed in ‘outrageous’ kit – home-made blouses of red or blue, serge knickerbockers, specially adapted boots and shinguards. Nettie claimed it was a serious attempt to break the mould, to prove that women could play ‘a man’s game’ and that they had every right to play. More significantly perhaps, they promised to challenge men’s ideas of feminism.

Whether they succeeded in their mission statement is open to debate. Enterprising and brave, they perhaps did modify a few concepts, but they were never accepted as serious footballers, and laid themselves open to serious criticism.

What counted against them was their ‘professionalism’ in that they charged admission, paid players or presented them with gifts and worked hard at marketing themselves. All this contrasted starkly with their amateurish attempts at actually playing football. One newspaper called it ‘a fraud on the public’.

After extensive publicity, over 10000 turned up for the opening match, each paying a ‘tanner’ (six pennies). Novelty value quickly faded. Cheers, laughter and ribaldry evolved into insults. Many fans left the ground well before the final whistle, setting a pattern for most of their games. But, if nothing else, it was a financial success with approximately £250 in gate receipts. Nettie’s squad realised they were onto a winner. Each player earned £5, some received a gift. Beatrice Fenn got a timepiece which she treasured for the rest of her life.

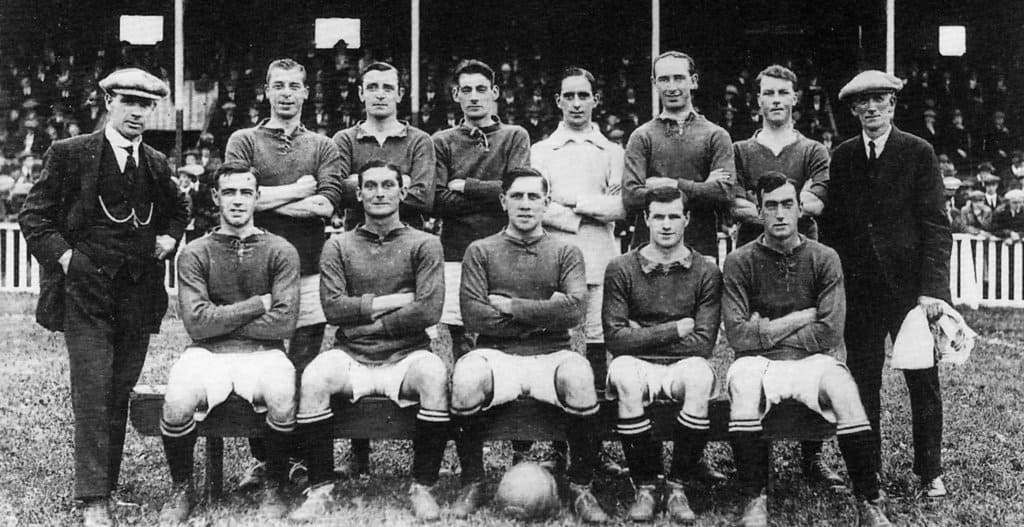

The idea of a tour was quickly raised. Clubs, recognising that the BLFC could be a money-spinner, offered venues throughout Britain although they discovered that the ladies – or the men behind them (one was the manager Alfred Hewitt Smith) – were hard-headed negotiators demanding the greater share of the gate money. They even hauled one club into the small claims court over a payment dispute.

Travelling by train and ferry and using temperance hotels, the British Ladies Football club appeared all over the country, sometimes watched by thousands. Occasionally, after a match, they climbed onto horse-drawn carriages to be hauled triumphantly through the streets, waving and calling to on-lookers like FA Cup Final winners.

But, as critics were quick to point out, their standard of play was abjectly poor and failed to improve. They had scant knowledge of the laws of the game. Too often they turned up late for a fixture or without enough players. Once or twice they went absent without leave, most notably when 4000 spectators at the Royal Ordnance ground waited in vain for them to appear.

All this fuelled the fire of the male Establishment who had never wanted them to succeed. The abuse grew, on the touchlines and in the Press. The Sketch, which, earlier, had taken a sympathetic approach, fired out a damning salvo in September 1895. ‘The mask has been torn off the British Ladies Football Club. It stands revealed as a purely money-making concern’.

Unfortunately, that accusation had some justification. Several players had connections with the stage, most notably Ellie Dunn who, in later years, emerged as Lily Flexmore, a contortionist who wowed audiences in USA with her leg over the shoulder, foot in the mouth trick. Some players used pseudonyms. Nettie J Honeyball was probably a Nellie Hudson, or possibly Mary Hutson. Ellie Dunn concealed herself as ‘R Coupland’. The goalkeeper ‘Mrs Graham’ was Helen Matthews, the only one with genuine footballing pedigree. And while originally thought that those with the time to play football two or three times a week must come from the affluent middle-class, Team Nettie included several from more modest environments who, presumably, would have needed paying. The question was asked: ‘Football club or travelling theatre?’

Even so, this adventurous, enthusiastic band of young women might still be viewed as the original Lionesses.

Colin Evans is a retired journalist

Published: 17th August 2022