Sir Christopher Wren died on 25th February 1723, leaving behind a great legacy as one of the most famous and distinguished architects responsible for some of Britain’s best known buildings.

His architectural marvels still surround us today; landmarks such as St Paul’s Cathedral, Kensington Palace and the Royal Observatory, to name just a few. As you walk around London, Wren’s legacy has made up the blueprint of the city, a living legacy to one of Britain’s most illustrious architects.

He was born on 20th October 1632 in Wiltshire, the son of a rector. His natural talent was evident from an early age, showing particular aptitude in mathematics and the skill of invention. His talent was nurtured by receiving a good education at Westminster School followed by Oxford University.

As an inventor, he began building up his knowledge of science through experimentation. This included working with sundials and creating a model of the solar system. He would also create a pneumatic machine and experiment with the idea of a device that would enable you to write in the dark. This exemplified his creative mind set, his scientific acumen as well as his artistic talent and ability to experiment with new technologies. Wren was able to think outside the confines of the traditional ideas of his time which put him at the forefront of discovery and invention.

By 1657 he had been appointed as a professor at Gresham College in London teaching astronomy. His thirst for knowledge was satisfied in his participation in a scientific group where likeminded individuals met on a weekly basis to exchange ideas. This was a precursor to the establishment of the Royal Society. In 1662 this came into fruition when the group received a Royal Charter from Charles II and formally became “The Royal Society of London for the promotion of Natural Knowledge”.

This was an academic coup for Wren and his colleagues as founding members of the Society. Furthermore, Wren would go on to become President of the Royal Society in the following year, from 1680 until 1682. His prestigious academic career grew from strength to strength and would continue on this trajectory in the years to come when he became a professor of Astronomy at Oxford University.

Wren’s participation in the Royal Society had put him on the map both socially and academically. His work was admired by the likes of Isaac Newton. Furthermore, through his work he gained the attention of King Charles II who was keen to approach him with a proposal of a royal commission involving the re-fortification of Tangier. King Charles had noticed his talent and seized the opportunity to have a skilled mathematician in charge. Wren was not to take him up on this offer but it did nothing to harm his future job prospects in this field.

Wren’s background in mathematics and physics, as well as his artistic inclinations exhibited at a young age, would serve him well in the field of design and construction. In the 1660’s Wren took his first tentative steps into the world of architecture and design. He had been offered the chance by his uncle, the Bishop of Ely who commissioned him to design the chapel at Pembroke College, Cambridge. This religious design would be the first of many churches created by Wren in his career.

Not long after this commission, he submitted a proposal for the design of the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford. Rather distinctively this commission was his first to include a dome design, a distinctive feature which would be used in his later creations. Inspired by the classical structures of Ancient Rome, combined with a modern touch, Wren was already developing a distinctive style.

In 1665 he embarked on a trip to Paris. It was here that he began to favour the elaborate designs typical of French and Italian baroque. At this time Wren found himself committing a great deal of time to his architectural projects, a decision that would win him great fame. It was not however uncommon for a man of his standing and academic skill to take up the task of designing buildings, as the formal profession of an architect in the seventeenth century had not been established.

In this era, it was typical for a well-educated gentleman to take up architecture as a kind of extra-curricular activity or hobby. It was viewed as simply an extension of applied mathematics, rather than a field entirely of its own. Unsurprisingly, Wren fitted into this category, after showing a keen interest in the basic principles of design and architecture whilst completing his academic studies. Being commissioned to create his own buildings appeared to be a natural progression in his career, a task to which he dedicated himself to wholeheartedly.

One of Wren’s defining moments as an architect and one that earned him the greatest reputation was the creation of St Paul’s Cathedral.

The project itself was a long time-consuming one, Wren having consulted unofficially on the repairs to the old cathedral structure as early as 1661. The design plans came into being in the spring of 1666 when it was revealed that Wren intended a dome structure for St Paul’s, a proposal that was accepted in August 1666. The plan however did not anticipate the tragedy that was to follow shortly afterwards: the Great Fire of London swept through the city leaving devastation in its wake.

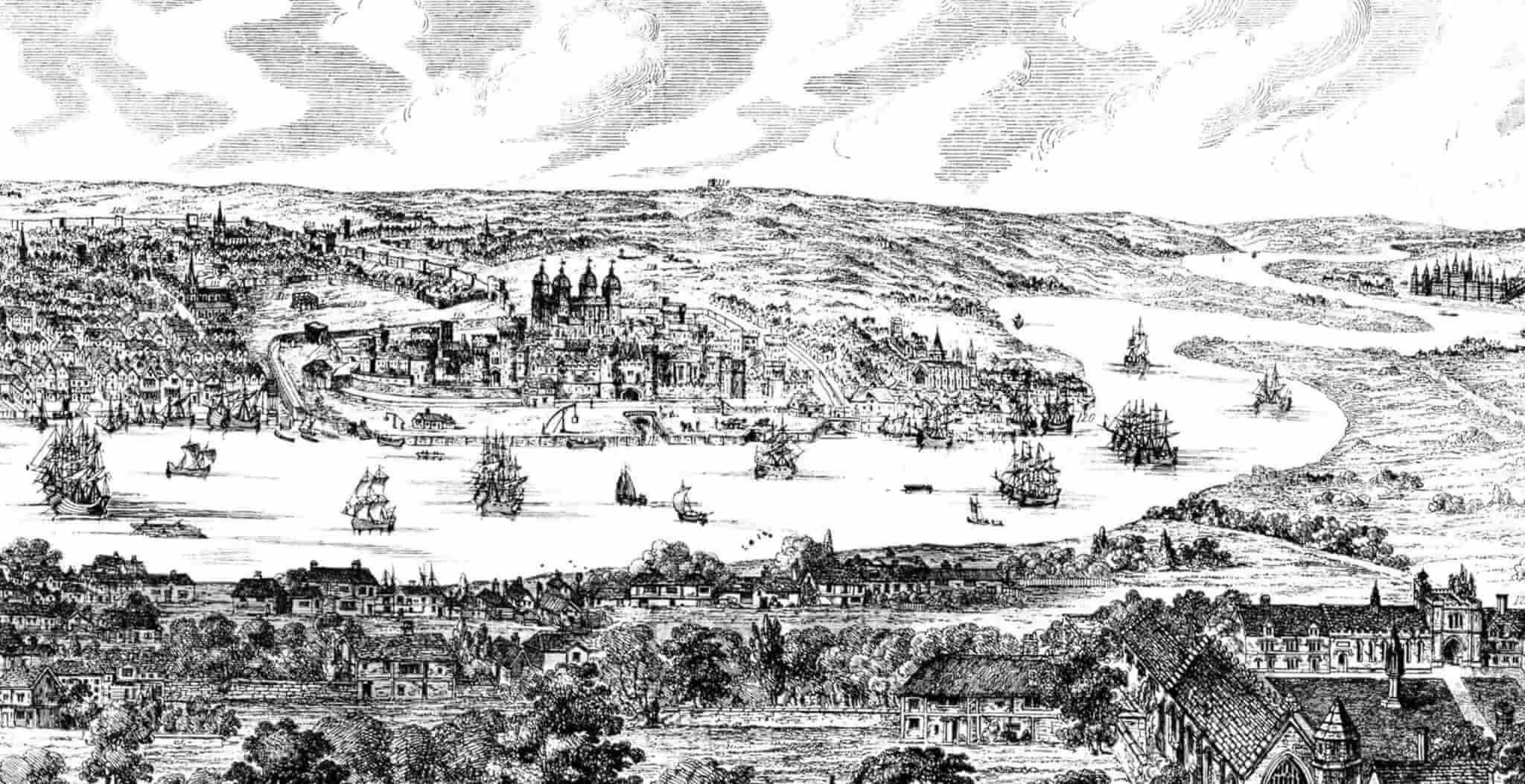

The fire had left London in ruins, old St Paul’s included, and around two-thirds of the City was left as burning embers. Upon hearing the news, Wren travelled to London and immediately got to work, firstly attempting to analyse the extent of the damage and then working out a rebuilding plan to submit to Charles II.

Wren was not the only person working on this project: others also had submitted their ideas, however the mere drawings of ideas was not enough, action needed to be taken. In 1667 the Rebuilding Act was passed which approved the essential constructions. Two years later Wren was installed after the King’s Surveyor of Works passed away. This was the opportunity of a lifetime which gave him control of all government buildings in the country. This was the rebuilding project that would cement his status and earn him the greatest architectural plaudits.

His plans were ambitious. His focus turned to the new St Paul’s Cathedral as well as his design work for around fifty one other city churches scattered around the city. For his work he would be knighted in 1673, whilst his crowning glory, St Paul’s Cathedral was declared officially complete by Parliament on Christmas Day 1711. Wren was able to see his masterpiece completed in his own lifetime.

His design has allowed the cathedral to become of the most popular and well-known sights in London, drawing crowds from all over the world. Its impressive dome was at the time one of the tallest buildings in London, reaching 365 feet in height, and is one of the largest domes in the world. His design won him great admiration whilst others viewed it with more caution as the style was rather “un-English”. St Paul’s has however remained a great landmark in the city.

Over time Wren would amass a great portfolio of architectural designs, including the Royal Observatory at Greenwich which he was commissioned to design in 1675. Wren was in fact responsible for choosing the location, situated on a hilltop overlooking the River Thames, subsequently work began on the observatory, concluding in 1676.

During his lifetime Wren undertook several royal commissions including in 1682 the task of designing a hospital for retired soldiers. Today, the Royal Hospital Chelsea remains as a retirement home for around 300 veterans. Wren was responsible for the design of the impressive chapel at the hospital, a highlight of his skill in creating religious buildings as well as the Great Hall, originally intended as a dining room.

In time his architectural prowess dominated the landscape, particularly in London but also in Cambridge where he designed Trinity College Library. Back in the city, after the death of Charles II who had issued so many royal commissions, the new king James II continued to give Wren further projects, including Hampton Court and Kensington Palace.

On 25th February he passed away at the age of ninety, Sir Christopher Wren became one of Britain’s best known architects, making valuable contributions to the infrastructure and skyline of Britain.

Wren will always be remembered through his creations, so much so that his epitaph reads:

“If you seek his memorial, look about you”.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th February 2023