It may seem odd to link together sport and the disposal of human remains, but in the latter half of the nineteenth century a growing campaign to legalise cremation was given a helping hand after a significant sporting defeat.

The practice of cremating the dead had disappeared from Britain from around the fifth century, as Christianity and the resurrection belief became more widespread. By the late 1800’s, however, disease and poor hygiene amongst the growing population had prompted a discussion on a number of social issues – one of which involved a small number of prominent figures advocating an alternative to the burial of bodies, although not supported by a suspicious public or the national press.

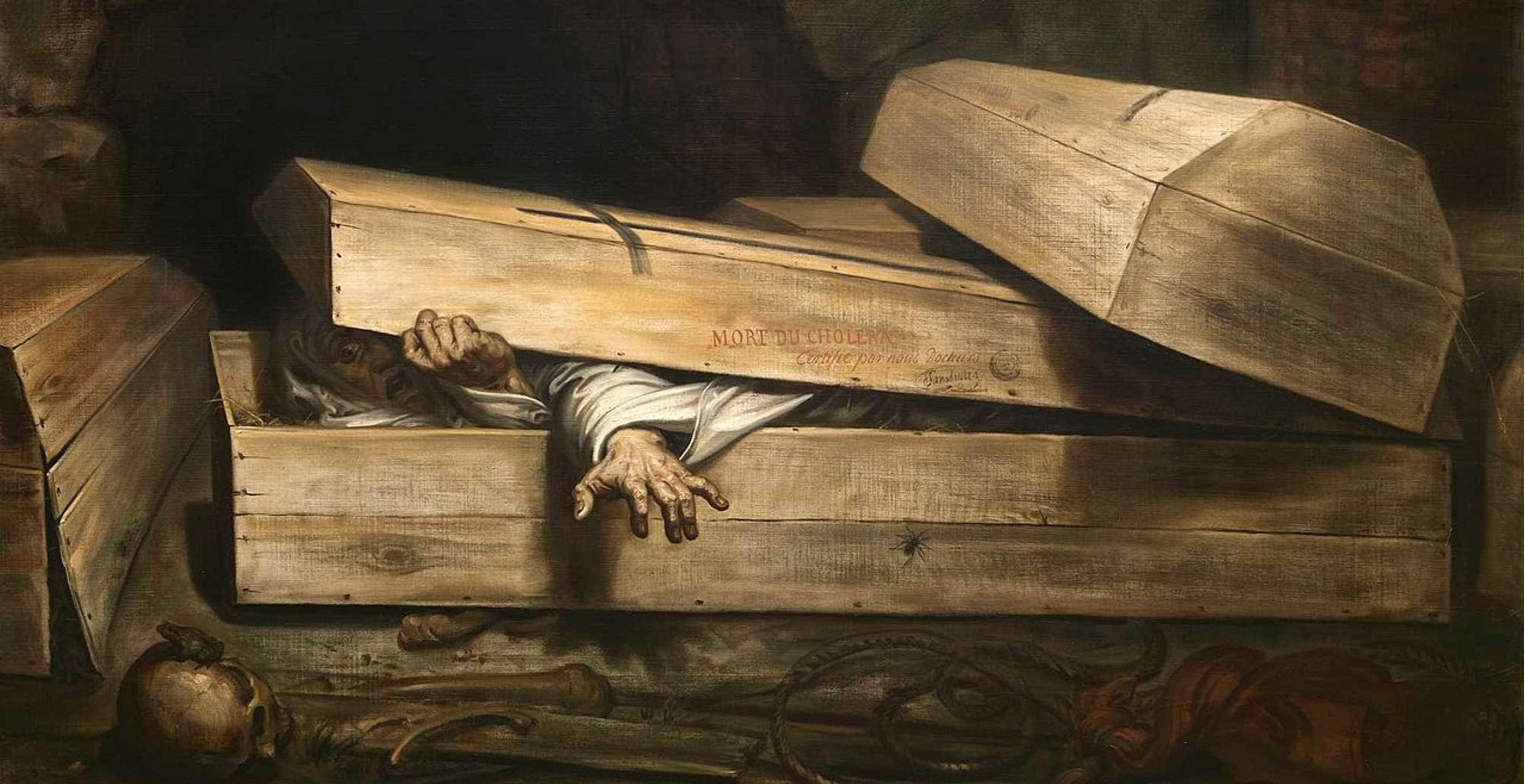

In 1874 Sir Henry Thompson, eminent surgeon and physician to Queen Victoria, founded The Cremation Society of England – later changed to Great Britain. Witnessing new furnace technology had encouraged Thompson to write an article entitled ‘The Treatment of the body after Death’ – published earlier in the year. Writing that “it was becoming a necessary sanitary precaution against the propagation of disease…”, he also thought that cremation would reduce burial costs, reduce the chances of being buried alive and that the ashes could be used as fertiliser.

Joining Thompson at an inaugural meeting in his house were a number of notable figures, including Anthony Trollope, artist John Everett Millais and Charles Shirley Brooks – a former editor of Punch and known by his middle name. A Declaration was approved, stating that “We, the undersigned, disprove the present custom of burying the dead and we desire to substitute some mode which shall rapidly resolve the body into its component elements by a process which cannot offend the living…until some better method is devised we desire to adopt that usually known as cremation.” The notice was placed in a number of papers, sparking a debate in the press. Ironically, having been one of the Society’s prime backers, Brooks died a few weeks later and was buried in Kensal Green cemetery, his wishes for cremation unable to be carried out by his family.

Despite the campaign gaining some attention, little could be achieved on a larger scale whilst the government was opposed to the idea. Towards the end of the 1870’s the Society optimistically bought some land next to Woking cemetery from the London Necropolis Company, in the hope of eventually building its first crematorium. Testing on animal carcasses was carried out but plans for a building were foiled by hostility from the local inhabitants who took their protests to the Home Secretary. The decision went against the Society, with the Home Secretary’s refusal to allow permission until an Act of Parliament was passed based on his fear that cremation could be used to hide evidence of foul play on a body.

Reluctant to break the law, it seemed that all the Society could now do was try and get its message across to the general public: the campaign was gaining some support but it needed more ways to draw attention to the information. Help would soon arrive, however, and it would come from an unexpected source.

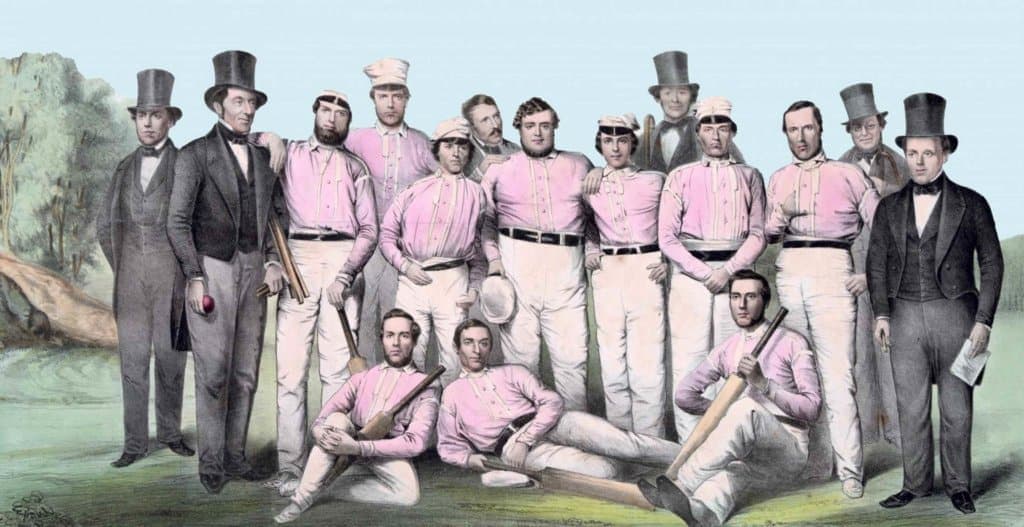

In August 1882 the touring Australian cricketers played a strong England side in the season’s only Test match. Spectators at The Oval witnessed a low-scoring match over two days, culminating in such a tense finish that one onlooker was reported to have died from a heart attack whilst another apparently chewed through his own umbrella handle. Thanks to their star bowler, Frederick ‘the Demon’ Spofforth, the visitors bowled England out for 77 in their second innings, recovering from a seemingly hopeless position to win by seven runs. It was the first time that England had been beaten at home – the public was shocked and the players were heavily criticised in the press.

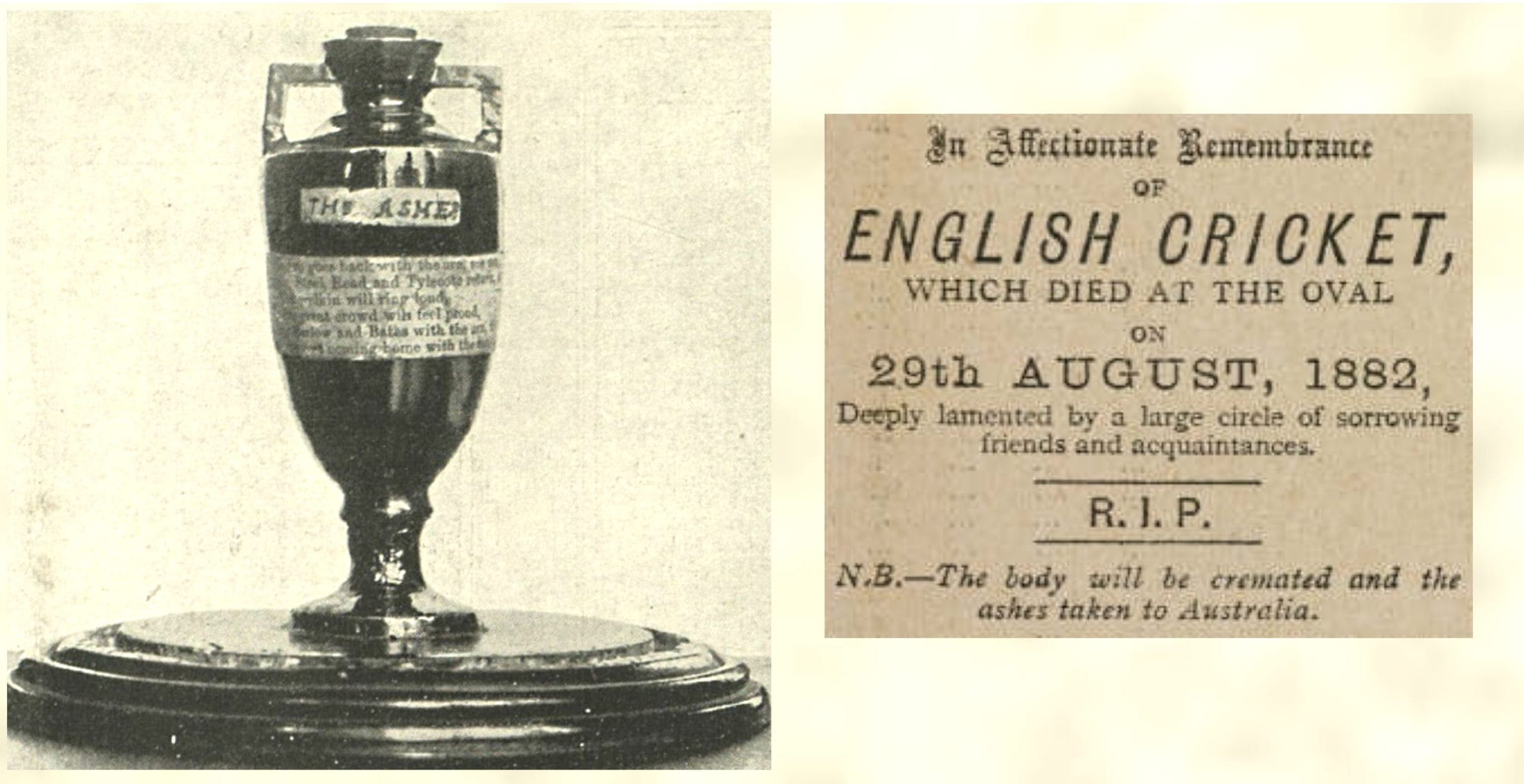

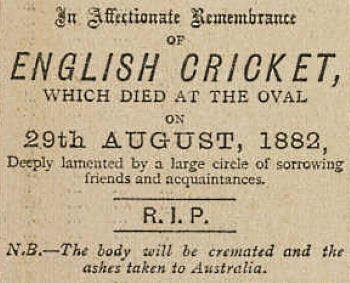

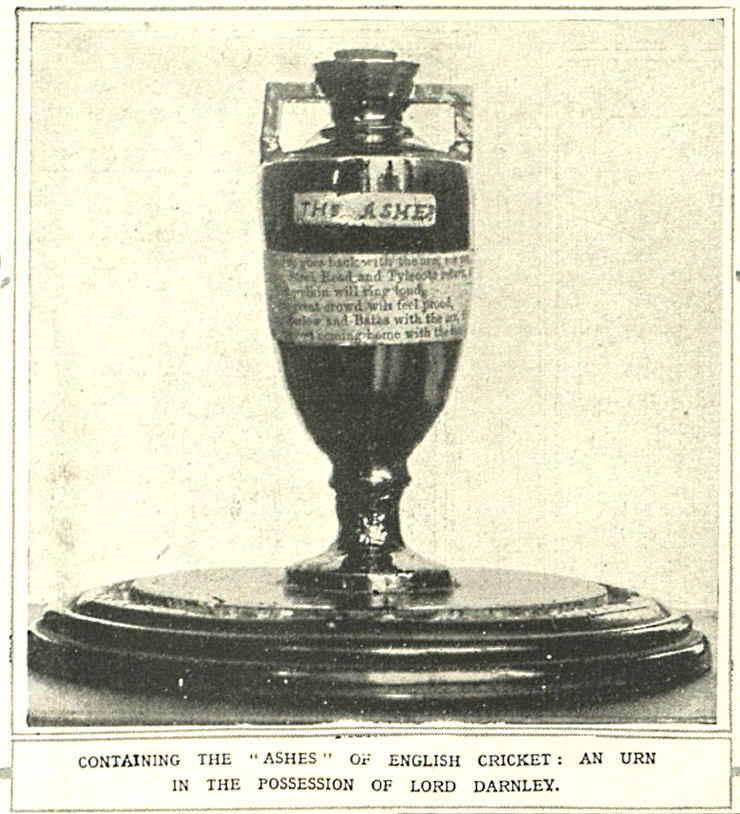

Within days an ‘obituary’ notice, mourning the death of English cricket, appeared in the ‘Sporting Times’. After noting the deep sorrow of friends and acquaintances, the notice concluded that ‘the body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia’. Its author was Reginald Shirley Brooks, the son of Shirley Brooks, one of the leading signatories of the 1874 Declaration.

The mock ‘obituary’, it appeared, was not just a satirical comment on the state of English cricket but an opportunity to make a clever political point – one that the author supported and would reach the paper’s large readership. Brooks knew exactly what he was doing by mentioning cremation: like his father, he was a journalist and was known for his irreverent articles for ‘Punch’ at the time. Whilst the notice is now remembered as the origin of the Ashes legend, the subtle wording was a highly effective publicity stunt for the campaign.

The Cremation Society continued to try and win over public opinion and a breakthrough came in 1884, when a legal hearing declared that cremation was legal, allowing the practice to be carried out if requested.

Three cremations were carried out at Woking in 1885, with the first being Mrs Jeanette Pickersgill, a poet and artist. Such was the shocking thought, shared by the majority of people, that cremation might lead to being burned alive, that it required two doctors to certify the death. From a small start, nearly one hundred further cremations took place at Woking over the next seven years, the rising demand causing a second building to be built at the site in 1892. Importantly, a chapel was also built, allowing mourners to congregate as they would have done at a graveside burial.

Although still not officially approved in law by an Act of Parliament, the practice of cremation was steadily becoming more acceptable and the Society supported the establishment of new crematoria in Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow during the last decade of the nineteenth century. In 1902, nearly thirty years after the original Declaration, the Cremation Act was eventually passed, allowing burial authorities to legally establish crematoria. The Society’s campaign had finally been successful, although there were still many people to be convinced. Over the first few decades of the new century, however, public opinion steadily began to change in favour. Today almost eighty per cent of funerals in the UK take place by cremation, a figure that Sir Henry Thompson could have barely envisaged in 1874.

England’s cricketers may have played an unwitting part in the promotion of a major social change but their performance provided the opportunity for Reginald Shirley Brooks to provide some impetus to a campaign that seemed to be struggling for support. His mocking ‘ashes’ led to the subsequent creation of cricket’s Ashes, but their satirical meaning played a distinctive part in promoting a revolutionary nineteenth century movement.

By Martin Claytor. Martin Claytor is a freelance writer with a particular interest in sport, particularly cricket, and history.

Published: August 2nd, 2021.