The pasty has been a documented part of the British diet since the 13th Century, at this time being devoured by the rich upper classes and royalty. The fillings were varied and rich; venison, beef, lamb and seafood like eels, flavoured with rich gravies and fruits. It wasn’t until the 17th and 18th centuries that the pasty was adopted by miners and farm workers in Cornwall as a means for providing themselves with easy, tasty and sustaining meals while they worked. And so the humble Cornish Pasty was born.

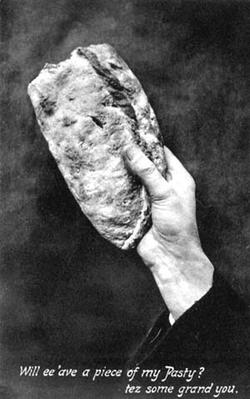

The wives of Cornish tin miners would lovingly prepare these all-in-one meals to provide sustenance for their spouses during their gruelling days down the dark, damp mines, working at such depths it wasn’t possible for them to surface at lunchtime. A typical pasty is simply a filling of choice sealed within a circle of pastry, one edge crimped into a thick crust . A good pasty could survive being dropped down a mine shaft! The crust served as a means of holding the pasty with dirty hands without contaminating the meal. Arsenic commonly accompanies tin within the ore that they were mining so, to avoid arsenic poisoning in particular, it was an essential part of the pasty.

The traditional recipe for the pasty filling is beef with potato, onion and swede, which when cooked together forms a rich gravy, all sealed in its own packet! As meat was much more expensive in the 17th and 18th centuries, its presence was scarce and so pasties traditionally contained much more vegetable than today. The presence of carrot in a pasty, although common now, was originally the mark of an inferior pasty.

Filling ideas are endless however, and can be as diverse as your taste will take you. There is much debate as to whether the ingredients should be mixed together before they are put in the pasty or lined up on the pastry in a certain order, with pastry partitions. However, there is agreement that the meat should be chopped (not necessarily minced), the vegetables sliced and none should be cooked before they are sealed within the pastry. It is this that makes the Cornish pasty different from other similar foods.

It was such a commonly used method of eating amongst the miners that some mines had stoves down the mine shafts specifically to cook the raw pasties. And this is how the well known British rhyme “Oggie, Oggie, Oggie” came about. “Oggie” stems from “Hoggan”, Cornish for pasty and it was shouted down the mine shaft by the bal-maidens who were cooking the pasties, when they were ready for eating. In reply, the miners would shout “Oi, Oi, Oi!” However, if they were cooked in the mornings, the pastry could keep the fillings warm for 8-10 hours and, when held close to the body, keep the miners warm too.

It was also common for the pasties to provide not only a hearty, savoury main course lunch, but also a sweet or fruity desert course. The savoury filling would be cooked at one end of the crescent and the sweet course at the other end. Hopefully these ends would be marked on the outside too!

Superstition and Tradition

The pasty is such a celebrated emblem for Cornwall that when the Cornish rugby team play a significant match a giant pasty is suspended above the bar before the game begins. And, speaking of giant pasties, one Cornish Young Farmers group decided to celebrate the symbol by creating the largest on record in 1985; 32 feet long! Although there are now many national businesses that trade in Cornish pasties, any local would tell you that none compare to traditional home-baked pasties.

As with a lot of British cultural symbols, there are superstitions and beliefs surrounding the humble pasty that have been passed on through the ages and accepted as ritual. Firstly, it was said that the Devil would never cross the River Tamar into Cornwall for fear of becoming a filling of a Cornish pasty after hearing of the Cornish women’s inclination to turn anything into a tasty filling!

The next relates to the crusts of the pasty. A Cornish wife would mark her husband’s pasty with his initials so that if he saved some of his pasty for an afternoon break, he could distinguish his from his colleagues. It was also so that the miner could leave part of his pasty and the crust to the “Knockers”. The Knockers are mischievous “little people”, or sprites, who live in the mines and were believed to cause havoc and misfortune unless they were bribed with small amounts of food. The initials carved into the pasties, it is assumed, made sure that those miners who left their crusts for the “Knockers” could be determined from those who didn’t.

In the 13th century when pasties were part of the diet of the rich and aristocratic, seafood was a common filling. However, in Cornwall, a county much in tune and dependant on the sea, the use of seafood in a pasty was unthinkable and inappropriate. Amongst the most superstitious of Cornish fisherman, even having a pasty on board their ship was believed to bring bad tidings! This belief is thought to have been started by the Cornish tin mining families who didn’t want their ingenious pasty invention to be adopted by the fishing trade.

They may not have wanted another trade to use the idea but when migrants from the Cornish tin mining community moved into other counties of England and also across to America, in search of work, they took with them their pastry crescent filled with a hearty meal.

More Information

The Cornish Pasty Association – Protecting the Cornish Pasty. The Association has gained European protected (PGI) status for the Cornish Pasty, which means that only pasties made in Cornwall, to a traditional recipe and manner can legally be called Cornish pasties.

Published: 12th May 2015