In the days when societies depended on horses for transport and the production of food, the ability to control horses was a valuable skill. Those who were extremely knowledgeable about the animals and could train them to work successfully were often seen as magical figures. Tales were whispered about the various techniques they used to gain mastery over the horse.

While skilled horse handlers were valued throughout the British Isles, two areas were particularly famous for their horsemen. The first was East Anglia, where the Toadmen (and a few Toadwomen) were still practising their techniques in the middle of the 20th century as the age of the working horse came to an end.

The second was Aberdeenshire in Scotland, where the Society of the Horseman’s Word (also known as the Society of the Horseman’s Grip an’ Word) would invite would-be initiates to their rites through the mysterious appearance on their beds of an envelope with a hair from a horse’s tail in it.

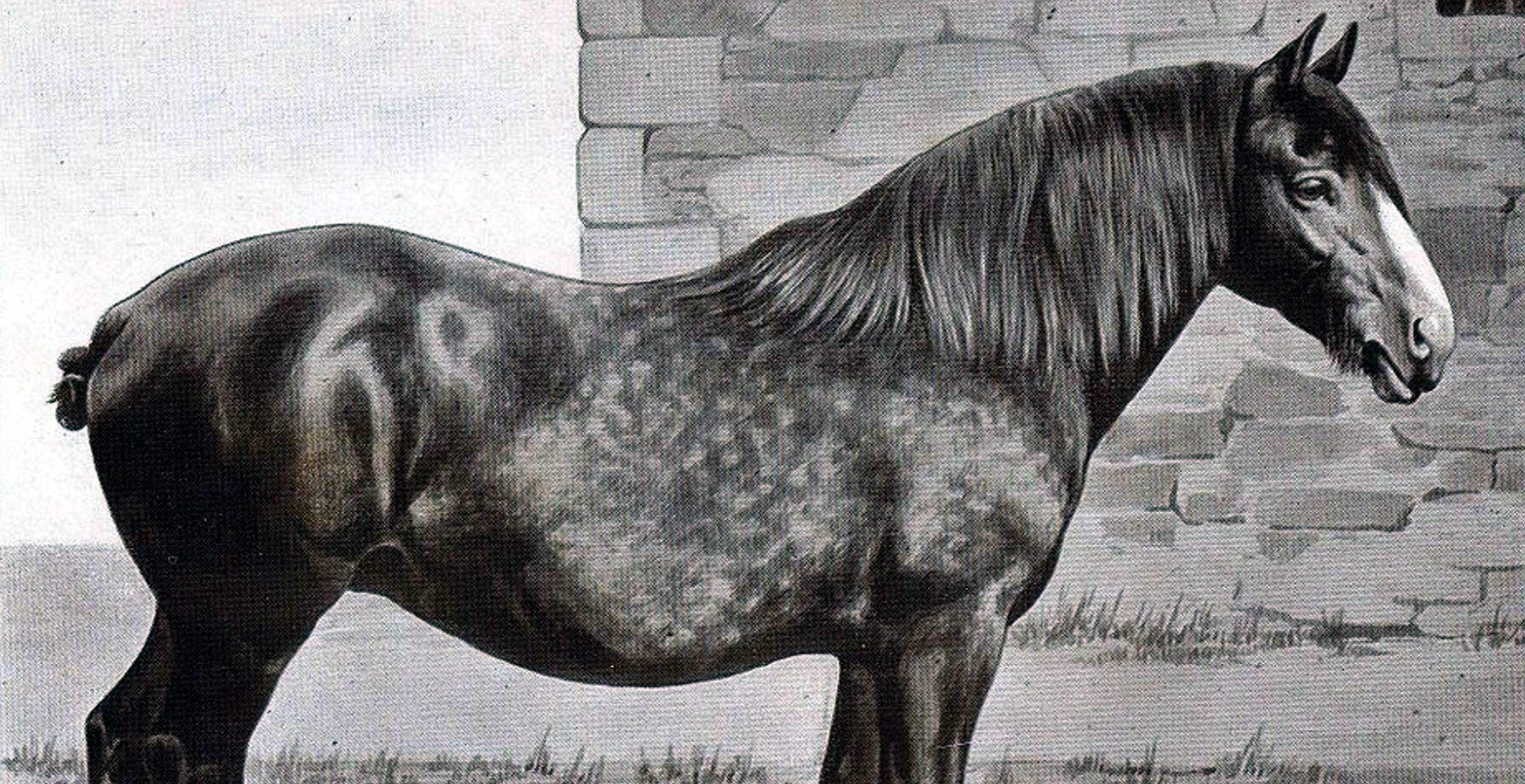

The East Anglian tradition appears to have been a folkloric one with deep roots. It is hard to tell how ancient some of the activities might have been, but it is worth noting that this region included the territory of the Iron Age Iceni who were known as horse breeders and trainers. A tradition of producing quality horses continued into the 19th century with the famed Suffolk Punches and very fast Norfolk Roadsters and Trotters.

Gold Iceni coin, showing a horse in the centre of the coin, wheel above and daisy below. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands license.

Gold Iceni coin, showing a horse in the centre of the coin, wheel above and daisy below. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands license.

As their name suggests, the skills of the Toadmen and Toadwomen arose from their connection to an animal that has always been seen as having magical qualities – the toad. Stories of their rites vary, but at the heart of most of them is the acquisition of a bone from a toad that gives the owner power over man and beast. To get the bone, a toad had to be killed and buried (some say buried on an anthill until its flesh was eaten away) and subjected to certain rites.

The would-be Toadman (or woman) would take the bones of the toad to a stream at midnight. There, under the moon, they would throw the bones into the running water and watch for the one that would separate from the others and float upstream. Not surprisingly, this supernatural contrariness to the natural order marked it out as having special powers.

Toad bones could be put to all sorts of uses but as horses played such an important role in the everyday life of local communities, they often appear in spells and stories relating to this animal. The bones could be used, for instance, to stop a horse so that it would refuse to go on until the Toadman or Toadwoman released it from their spell.

The 19th century Horsemen of north east Scotland were an altogether different phenomenon, much closer to a guild. Aspects of their rites are reminiscent of those of Freemasonry and there was also plenty of opportunity for the kind of tricks and rough treatment that accompanied the entrance of all new apprentices into a craft.

Being invited to join the Society of the Horseman’s Word was a mark of distinction. Its members were mainly ploughmen (plew, ploo or pleuchmen in Scots) and they wielded great power. While their skills with horses may have been viewed as having occult origins, they had power in a very real sense as providers of food for the entire nation. Through songs and stories, the ploughmen reminded everyone, from king to commoner, of their dependency on the plough and the animals that drew it.

If the initiate took up his invitation, he would go to an allocated place, often the hay or chaff barn, bearing offerings of whisky and bread. Once there he would be blindfolded and led through a series of questions and responses by a guide, a “brother” who was already a member of the society. The rituals included curious twists on classical and biblical tales, apparent threats to the initiate including a noose round the neck, and atrocious puns, all backed up with drinks of beer.

The Biblical Tubal Cain played a prominent role in the rites as the first blacksmith and tiller of the ground. The devil, or rather the fallen angel Lucifer, also put in an appearance in the form of a goat’s leg which the initiate, still wearing a blindfold, had to shake.

There was one piece of real knowledge embedded in the ritual, though. That was the Horseman’s word itself, which some say was the Latin “sic jubeo”, meaning “I conquer this way”. Others however, reveal that the word was “eno”, which is “one” backwards. Whether reversed or pronounced in the correct way, “one” was the key to the truth. Unless the ploughman could know his horses and himself as “one”, he would never succeed. He had to treat his horses as he would wish to be treated himself. There lay true power.

In fact, the author of “The Society of the Horseman’s Word”, published early in the 21st century, argues the case for the Society being possibly the prototype of an animal welfare society. The ploughman was nothing without his horses, and the quickest way to fall from grace in the society was to treat them badly.

It is worth mentioning that Scotland in the 19th century was at the cutting edge – pun intended – of an agricultural revolution. While harvesting cereals was still mostly done by hand, often still using a sickle rather than a scythe, many Scottish engineers were working hard to produce better ploughs.

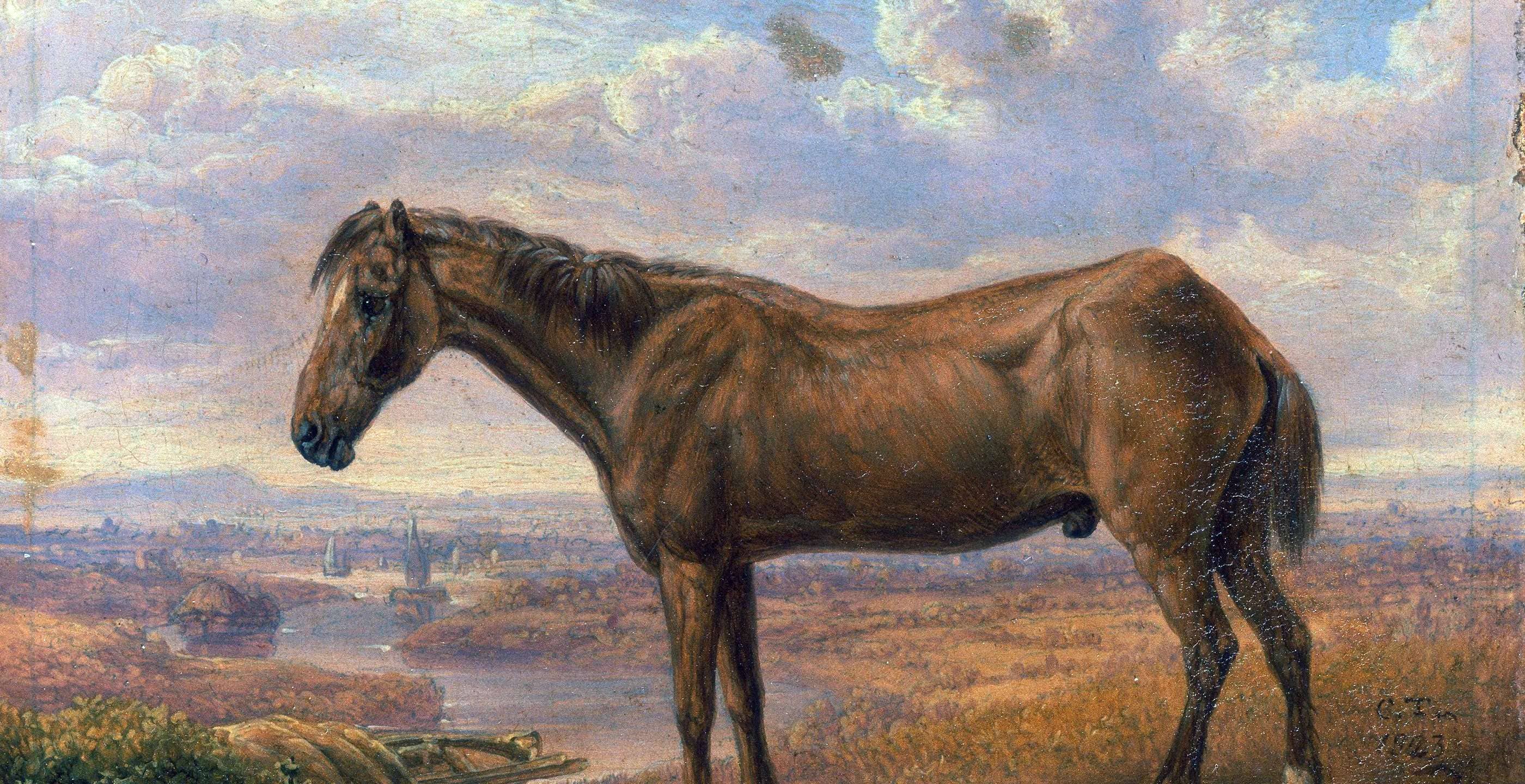

When Robert Burns the “pleughman poet” was farming at Ellisland Farm in the late 18th century, for instance, manoeuvring the unwieldy primitive plough had been a communal affair. The whole family helped, clearing stones and tough weeds from the way, urging on the team (often a mixed team of oxen and horses) and adding their weight to the ploughboard to make it cut properly. It required a lot of effort.

By the 19th century, advances in plough design made ploughing a much more efficient affair, meaning the plough could be handled by one man and a pair of the specially bred heavy horses that had also emerged as part of the agricultural improvements of the 18th century. By the 19th century, Scotland had developed its own breed of working horse to match the English Shires – the Clydesdale.

The strange rituals of the ploughmen can be set against the rational, scientific approach to agriculture that was emerging. Since ploughing was skilled and relatively high-status work, protecting the craft made sense and ensured that all the “brothers” maintained a united front. This was important when it came to dealing with difficult employers or anyone who tried to interfere with their work, including making unreasonable demands on the horses. Since a ploughman and his horses were “one”, anything that put the animals at risk was viewed as a personal insult to themselves.

In between the serious business of producing the nation’s food and taking the best care of the animals who made it all possible, there was plenty of time for socialising. The jolly ploughmen were fond of a dram and a song, and had a reputation for having a special way with womenfolk as well as horses – or so they liked to say!

There were also certain secret elixirs and unguents that were believed to have an influence over horses. Horses do have a strong sense of smell and can be encouraged or deterred by certain scents. By rubbing one of the magic potions on the hand and holding it under the nose of the horse, or on the horse itself, the horseman could either encourage the animal or bring it to a dead halt, or so it was thought.

One tip from the gypsy horse copers was to carry a ball made from oats and honey in the armpit and feed bits of it to the horse. This, it was believed, gave the carrier power over animals. It’s true that most horses love oats and sweet tasting foods, and possibly even the added sweat would provide the salt which horses need! The truth was, of course, that it was care and trust that made a horseman, not magic, as the following poem shows:

“Here’s to them that work horses

Bad luck to them that is cruel

Let perseverance be their guide

And nature be their rule.”

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.