In the first decade of the 20th century, the British people could look back on the achievements of the Victorian era. Britain had become the “workshop of the world”; it had been in the vanguard of scientific and technical progress; it had an Empire “on which the sun never set”, and a powerful navy to defend it. If they looked forward, they expected such progress to continue.

Arthur Mee and a group of like-minded men and women set about a colossal project to provide children of all ages with the first ever work designed to meet their needs. This Children’s Encyclopædia first appeared in fortnightly instalments between 1908 and 1910, when it was published in eight large volumes. (It was not alphabetical, but consisted on articles on a variety of subjects.) It went through many subsequent editions: the last was in 1964 (after Mee’s death).

The 1910 edition gives us fascinating insights into what the Edwardians thought, how they lived and what they knew (or, in surprisingly few cases, did not know). Its outlook was optimistic: “The world is a beautiful place filled with living things, and men and women and boys and girls are the masters of creation.” In this short article we can look at just some of the main topics.

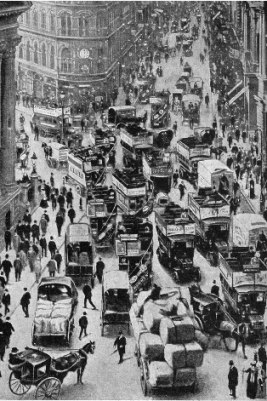

“The busiest street in the world” (Mansion House Street, London).

Science

Knowledge of the nature of the earth and the universe had greatly expanded. The Encyclopædia had not caught up with Einstein – he had only recently published his theory of relativity – and the concepts of the “Big Bang”’ and the expanding universe were still several decades away. Still, from articles on WONDER, NATURE, LIFE, THE EARTH, the young reader would have formed a clear idea of the vastness of the universe, of the solar system and of the formation of the earth, although some of these articles would have been challenging even for an intelligent teenager.

The nature of heat and light was explained. The Encyclopædia had difficulty over gravity, and its concept of the “ether” as the medium in space through which energy travelled, though not illogical, was soon to be discarded by scientists. The movement of tectonic plates, and their role in provoking earthquakes, was another unknown phenomenon.

The readers were left in no doubt about evolution. Man was presented as the highest form of life, though the Encyclopædia avoided asserting too clearly that he descended from the apes: Darwin’s work was still controversial.

Science and religion

No admission of conflict between science and religion was allowed to creep in. Indeed, where scientific knowledge reached its limits, as in dealing with the origins of the universe, of life itself and of man’s ultimate destiny, the writers resorted to a circumlocution such as “Nature” or “the ultimate Author of all things”, rather than refer explicitly to “God”. This caution did not reflect the on-going debate at the time. Should the young readers not have been offered a more balanced view of the issues involved? The Encyclopædia probably had to avoid controversy over this issue if it was to be widely accepted.

Young minds were left in no doubt that Christianity was far superior to any other world religion. In this, the Encyclopædia reflected the attitudes of the time, closely linked to the colonial experience.

Society

The conditions of the British working-class, though improved from Victorian times, still left much to be desired in terms of housing, working conditions, health and education.

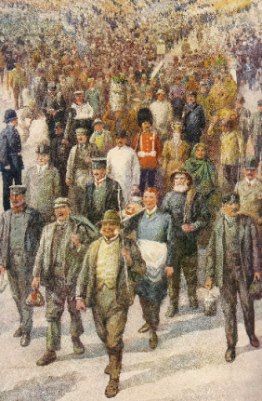

“The daily army of workers all over our land” (they look happy and vigorous).

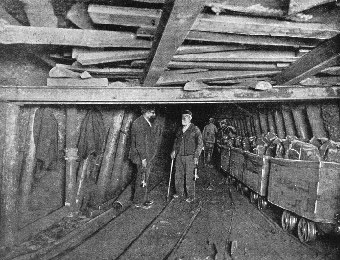

Reading the Encyclopædia, one has little inkling of this. There was brief mention of the bad working conditions in factories, but where workers are depicted, they appear as strong, healthy, willing. A particularly telling demonstration of this attitude appeared in contrasting pictures of miners working at the coal-face and of a prosperous-looking family sitting comfortably at the fireside.

Down a coal-mine (a more realistic picture of working conditions).

A fireside scene (a prosperous, comfortable middle-class family…).

The well-dressed children shown in other illustrations confirm not only that the Encyclopædia was aimed at the prosperous classes. There was hardly any mention of child neglect and deprivation, though this was a major issue at the time and was targeted by the 1908 Children Act.

The class divide would have been conspicuous in well-to-do families which could afford domestic help. Yet servants are hardly ever mentioned: their subordinate role seems to be taken for granted, and nothing is said about their conditions of employment. Thus the Encyclopædia reflected the class-consciousness of its era, and did little to promote a more responsible social attitude. Indeed, expressions such as ‘the lower classes’ were used without hesitation, and there is even a hint of the ‘social eugenics’ prevalent at the time.

The Encyclopædia was aimed at girls as well as boys: in stories of GOLDEN DEEDS there were heroines as well as heroes; THINGS TO MAKE AND DO suggested different tasks for boys and girls – carpentry for the former, dress-making etc. for the latter – but there were also many activities which they could do together. However, the Encyclopædia gave little or no guidance as to the adult role of women, although the suffragette movement was at its peak.

Imperialism

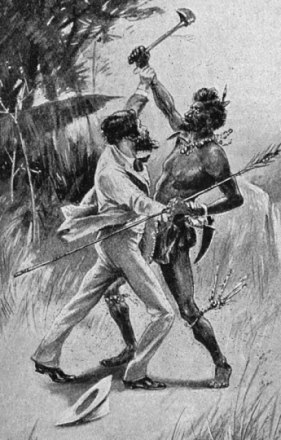

The Encyclopædia was proud of Britain’s supremacy in the world and of its great Empire. It justified Britain’s rule over other peoples in terms of bringing them civilisation (railways playing an important role) and of converting them to Christianity. The work of missionaries was on the whole described with approval, though one can detect some doubts in this respect. The writers had no doubt that the white man is superior, and that among the whites, British is best. In this, the Encyclopædia reflected the assumptions of its time; indeed, it was on the liberal side, stressing that the ‘lesser breeds’ should be treated with respect and that white rule entails duties as well as privileges.

A missionary and a “savage”.

Britain in the world

The Encyclopædia reflected Britain’s confidence in its economic and military power. It acknowledged a rising challenge from Germany, particularly in the construction of battleships, but it did not take this threat seriously. This may have been because it admired Germany for its scientific progress and its excellent education system; perhaps also because of misplaced confidence in the links between the Kaiser and the British royal family.

It failed to point out the dangers in the historic antagonism between France and Germany. Though it explained well the complexities of the Balkans, it disregarded the potential dangers there and was much too favourable to Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary, whose misjudgements would subsequently precipitate the conflagration of 1914. Consequently, the Encyclopædia gave no hint of the coming disaster. Some of its readers, and many of their fathers, uncles or elder brothers, would soon be called up to fight and die in the trenches of Flanders. There, ideals of self-sacrifice and gallantry learnt from the Encyclopædia would be put to the ultimate test; many would not return. After 1914–18, nothing would be quite the same for Britain or for many other countries.

“Your little friends in other lands”.

From Michael Tracy’s book: The World of the Edwardian Child – as seen in Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopædia, 1908—1910. Published 2008.