The literary movement that spread throughout Europe in the wake of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars furnished Britain with some of its most celebrated literary figures. Straddling the period between 1789 and the 1820s, this development would come to be called Romanticism, with poets like William Wordsworth (1770-1850) and Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) at its pinnacle. Such figures have cast an enduring spell over the nation, with Wordsworth’s focus on the Lakeland landscape evoking images of daffodils in bloom and Shelley’s verse tackling both the pastoral and political. A slightly less celebrated figure from this vibrant period is Thomas De Quincey, a writer who idolised but never emulated Wordsworth, despite his talent. De Quincey’s story is one of addiction and the city, and undoubtedly throws light on his Gothic spin on the Romantic ideal.

Born in Manchester on August 15th 1785 to Thomas and Elizabeth, a sickly young Thomas was soon at odds with his mercantile family. Matters were not improved when, at the age of 6 or 7 his father died, leaving him in the care of a strict mother who severely hampered his confidence. More instructive at this period is perhaps the death of his sister, Elizabeth, a sacred figure in De Quincey’s eyes who through her passing paradoxically helped the writer towards his future achievements. It is no coincidence that De Quincey’s first engagement with Wordsworth came through the poem ‘We Are Seven’, which deals with a young girl’s perception of death, and it is not hard to imagine the young scholar, having been despatched to boarding school, taking solace in Romantic verse.

De Quincey proved himself a capable scholar at school in Manchester and Bath, where he noted that he could “converse in Greek fluently and without embarrassment.” However, on realisation that he was academically superior to his masters, he executed an escape with the intention of presenting himself to his idol, Wordsworth. On this occasion the adventurer did not reach the Lake District and between July and November 1802, spent his time tramping about until, bereft of funds, he made his way to London.

His first encounter with the capital was defined by poor health and degradation, as he experienced a life typical to its poor inhabitants during this period. Among the people he encountered was a 17-year-old ‘street-walker’ called Ann, who in addition to treating the youth as a brother, spent her only money securing him a lifesaving tonic to combat exhaustion. It is testament to the impact of Ann’s kindness that she plays a major part in his celebrated work, the autobiographical, ‘Confessions of an English Opium-Eater’, where the author recalls “the noble action which she there performed.”

Eventually reunited with his family, De Quincey returned to education but eventually left Worcester College, Oxford without his degree. It was during this period that he first sampled opium, in the form of a laudanum tincture taken for a facial neuralgia, and was provided with the catalyst for ‘Confessions’. The price of his achievement was a haunting addiction, as his love for the ‘celestial pleasures’ would cling to him for the rest of his life.

In 1807 De Quincey realised his childhood ambition and began to develop a friendship with Wordsworth, with the pair’s association eventually resulting in his relocating to the Lake District, where an immersion in Wordsworth’s literary haven enabled him to develop as a writer. Seemingly settled, in 1816, De Quincey married a farmer’s daughter named Margaret Simpson and in 1821, ‘Confessions’ was published in London Magazine, provoking profound discussion as a result of its illuminating approach to addiction and dark, impassioned prose.

Dora Wordsworth – Town End (Dove Cottage), Grasmere, watercolor

Dora Wordsworth – Town End (Dove Cottage), Grasmere, watercolorDespite his ties to Wordsworth and the Lake District, De Quincey’s masterpiece was a different take on the Romantic form of his contemporaries, with his ever lurking ‘ghastly phantoms.’ This was in no small part due to his addiction, as the title suggests, but in equal measure was also a product of his association with the city. Despite his family residing at Wordsworth’s Dove Cottage the writer continued to work in London as a journalist and combined with his intense experience as a youth, this ongoing link to the fast developing metropolis was profound.

In 1837 Margaret passed away and De Quincey moved to Edinburgh in a bid to escape debt. His relationship with Wordsworth had become sour, partly as a result of the poet’s haughty attitude towards his wife, and the rest of his work, including ‘Suspiria De Profundis’, another autobiographical piece, was composed under the dark cloud of reduced circumstances.

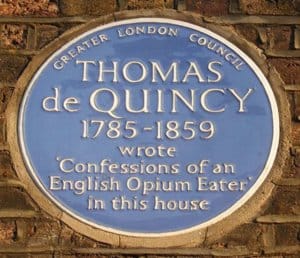

By the time of De Quincey’s death in 1859, and despite his numerous volumes of work including essays and translations, ‘Confessions’ was his only definitive piece of work. It seems highly fitting that a blue plaque now hangs in Tavistock St, London to identify the location where he worked on his text. The writer’s name may be misspelt but he will be remembered in the city as a darker, more urban alternative to the Romantic masters.

Photo above: Author Spudgun67, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

By Edward Cummings. Edward Cummings is in the last year of his degree and hoping to work towards a Masters degree in literary history. He is interested in all things historic and always looking to learn something new.