Living like a king was beyond the dreams of the average 19th century Londoner. However, if the plans of one young architect for a “Metropolitan Sepulchre” had come to fruition, the capital’s citizens would at least have been able to spend eternity like one. The only hitch was that unlike the Egyptian pharaohs in their exclusive tombs, he or she would be spending an afterlife crammed in with 5 million others.

Architect Thomas Willson’s audacious scheme for a giant pyramid mortuary for London was never implemented, yet as a concept and a curiosity it still attracts interest today. Willson put forward his plan in the early 1830s, at a time when the issue of how to dispose of London’s dead was reaching crisis point. In fact, it had been a concern for several centuries, having been recognised as a problem since the days of the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London that followed.

Christopher Wren had first suggested placing London’s graveyards in the countryside, just beyond the capital’s boundaries. However, it was only when the population of London had expanded with frightening speed, as a result of the wealth created by the industrial revolution and Britain’s rising influence as a commercial and imperial nation, that the issue began to be taken seriously. In 1760, the population of London was around three-quarters of a million. By 1801 at the first official census, it had reached 1,096,784. Fifteen years later, it was 1.4 million. By 1860 it would reach 3,188,485.

In Willson’s day, the city was beginning to understand the need to plan for its growing population. People were drawn to London from all over Britain and beyond, to participate in and share the wealth of its economic success. Women were in the majority, making up 54% of the total population. Many of them were young and working primarily in domestic service. Fertility rates were high and death rates, particularly infant mortality rates, were lower due to better hygiene and midwifery practices.

The greater the population, the greater the need for space for burials. The existing burial grounds, many dating back centuries, were already crammed with corpses laid one on top of another. When a new interment was needed, existing ones were often dug up and the remains scattered, making London’s crowded and sprawling cemeteries sources of diseases. The city authorities understood the need for better sanitation and housing to improve standards for the living. The question was: how to best provide for London’s growing population of the dead, now and in the future?

Confidently, Thomas Willson proposed his solution. A giant pyramid, its base covering 18 acres, would rise to a height of 94 stories on top of Primrose Hill, thus creating a total area of over 1000 acres filled with individual vaults, making enough room, he estimated, for 5 million deceased Londoners. The central location of Primrose Hill and the fact it was open space in an increasingly built-up London meant it had already been suggested as a potential burial ground.

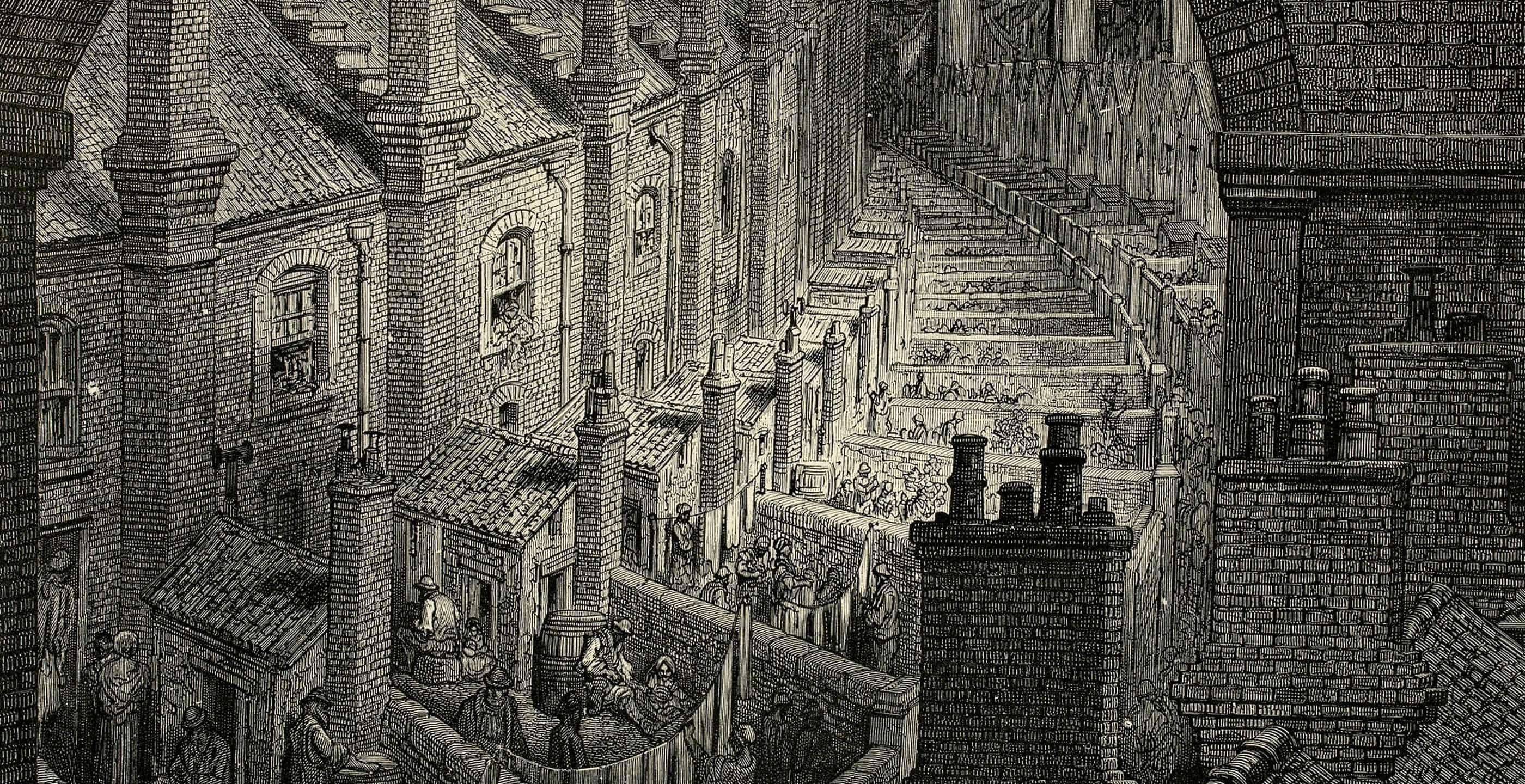

The Metropolitan Sepulchre (Willson’s Pyramid Mortuary), 1829 (Guildhall Library)

The Metropolitan Sepulchre (Willson’s Pyramid Mortuary), 1829 (Guildhall Library)

Willson had such faith in his idea that he drew up detailed plans and set up a company to promote it. On the ground floor, the main access was provided by four roads, each beginning at the middle of each side, creating the shape of an equal-armed cross. These gave access onto 15 concentric corridors along which the vaults, each with space for 24 bodies, were placed. The pattern continued on each floor, with fewer corridors at each level as the pyramid rose. Access was via ramps to make it easy for the funeral parties. The pyramid itself would be constructed from brick, but faced with granite to give an impressive appearance.

Somewhat reminiscent of a car park, or some modern budget hotels, Willson’s pyramid has labyrinthine corridors and identical room-like vaults one after another. It’s interesting to speculate just how Londoners would have coped with the concept. “Didn’t you say they put Auntie Ethel on floor 86, Vault 7?” “No, I said floor 87, Vault 6.” “Are you sure?” “’Course I’m sure. She was next to Uncle Arthur. Oh, no hang on…which floor is this anyway?” And so the mourners themselves might spend an eternity wandering around looking for their dead.

Willson’s pyramid was an astute piece of marketing and in many ways ahead of its time. The Victorian preoccupation with death and its rituals still lay in the future, but public interest in Egypt was growing. Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt and the knowledge brought back by the savants had created an antiquities race between Britain and France, and the British Museum had benefitted from it. The Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, decorated on the outside with images of the Egyptian deities Isis and Osiris, had hosted several Egyptian-themed exhibitions, including a reconstruction created by Giovanni Belzoni of two chambers of the tomb of King Seti I.

The public was enthralled by the mystery of ancient Egypt, including the Egyptian way of death. The study of ancient Egypt was often seen as an adjunct to Bible studies, so its popularity extended to all social classes. Egyptian themed architecture would appear in many British cities and even in rural locations, from factory buildings to individual tombs.

Willson had hit on a winning formula that evoked mystery and eternity. It also appealed to the hard-nosed commercialism of the age, with its “pile ‘em high and sell ‘em cheap” approach to death long predating the formula of the supermarket kings. He had costed it out at a rate of £50 per vault for families or parishes, and estimated that at 40,000 burials per annum, it would make a tidy return for the investors of the Pyramid General Cemetery Company. He was planning on it making £10,000,000 for the owners.

In the end, the authorities decided on a more conventional approach to burying the dead, with the creation of garden cemeteries such as Highgate and Kensal Green. The more distant ones enabled the use of that other great Victorian obsession, the railway.

Had Willson succeeded, his giant pyramid, topped with an obelisk and four times the height of St Paul’s, would probably have become London’s most notable and possibly controversial landmark.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.