Many of us are currently opening little doors to reveal chocolate, gin or lipgloss, culminating on December 25th when the real orgy of present-opening will begin. In some households, dogs and cats have their own advent calendars, while rabbits can feast on no-mince pies to get them in the festive spirit. And this year in particular, advent windows are popping up all over the Christmas-celebrating parts of the world, with Christmassy scenes constructed from household objects. Historically speaking, however, we’re celebrating advent all wrong. The point of this countdown to Christmas was originally to atone for sins during the year, not feast on tiny chocolates or thimble-sized beer samples.

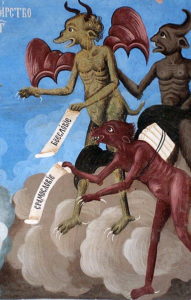

The origins of advent – roughly the month before Christmas – are unclear, but the word first appeared in the English language in the 10th century. It meant ‘approach of the gods’ or ‘coming’, both referring to Jesus’ coming into the world, and his ‘second coming’, when the dead would rise from their graves and await judgement. To get in the right frame of mind for these fiery torments, preachers would advise their congregations during Advent to contemplate the forthcoming ‘Day of Terror’ and the ‘Misery of Devils’, examining their consciences and calling themselves to account. Recommending close study of the Ten Commandments, one seventeenth century preacher exhorted readers to give up passion, prejudice and ‘undue Affections’, preparing themselves for the world to come.

Devils – a fresco detail from the Rila Monastery, Bulgaria. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Devils – a fresco detail from the Rila Monastery, Bulgaria. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

While there were no calendars, in some parts of medieval England advent boxes were created: these were wooden boxes covered with glass or a napkin, whipped off to reveal finely-dressed dolls representing Jesus and the Virgin Mary. They were decorated with ribbons, flowers and sometimes fruit, before being carried around the neighbourhood, where people would pay a small fee to view the tableau inside the box. In some communities, it was unlucky not to see the box before Christmas Day. Some of the dolls may have had sophisticated moveable joints, and people could dress them as an extra act of reverence.

Nativity scene. Photo by Chris Sowder on Unsplash.

Nativity scene. Photo by Chris Sowder on Unsplash.

This period of fasting and penitence would begin well before December: traditionally (and to this day in the Orthodox tradition), advent began on the 11th November, after St Martin’s Day. Rich, fatty geese were consumed to commemorate the saint’s life, as he was said to have hidden in a pen full of geese to avoid being ordained as a bishop. However, the geese – presumably prompted by a divine inspiration – honked and revealed Martin’s position, and he ended up becoming a bishop anyway. Just like Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday) before lent, decadent butter was also used up on St Martin’s Day, making for an extremely fatty feast! Traditions varied in different parts of Europe, but giving up meat, fat and ale, was often joined by abstinence from gambling, sex and – perhaps most surprisingly – getting married.

Citrussy fruit-filled stollen was invented as an advent dish, since bakers were not allowed to use butter during the period of fasting. Instead, they devised stollen: a hard cake made of flour, yeast, water, and an oil made from turnips. It’s shaped to resemble Jesus in swaddling clothes. Unsurprisingly, protests were lodged at this near-inedible creation, and eventually the inhabitants of Saxony were granted permission to use butter, as long as they paid the Church for the privilege. Today, the stollen we know and love seems like a reaction to this period of austerity: a huge dollop of butter is mixed into the dough, then after baking an entire stick is brushed all over it, followed by a slathering of sugar.

Stollen. Photo by Jennifer Pallian on Unsplash.

Stollen. Photo by Jennifer Pallian on Unsplash.

The fast of Advent lasted until Christmas, when twelve decadent days of feasting, singing and general carousing would begin, culminating in Twelfth Night or epiphany, where ‘king cakes’ are still baked in some countries. Whoever finds the bean inside their slice of cake is king for a day, while whoever finds the pea is queen. Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night riffs on the inversions that could happen in this time, as servants became masters, and jesters ruled the day. In the play, pompous servant Malvolio is tricked into believing that his mistress Olivia loves him, and prances around in yellow stockings, at the instigation of the servants and the household’s jester, Feste. Eventually, the mistress of the house takes back control, and order is restored (Malvolio’s dignity, on the other hand, is not). In Britain, wassailing still takes place on this date, singing and pouring cider over the apple trees to wake them up and make sure they produce for the year ahead.

Olivia’s House – Olivia, Maria and Malvolio (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, Act 3, Scene 4)

Olivia’s House – Olivia, Maria and Malvolio (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, Act 3, Scene 4)

After the fasting of advent, people really felt like they’d earned the enormous portions of Christmas Day. However, all that penitence proved difficult to keep up so the date of Advent was adjusted to begin later, on the Sunday before the month of December. It still officially begins in the Anglican calendar on this day, so this year Advent began on the 29th November, not the 1st of December as is commonly celebrated by the consumption of tiny chocolates.

Which date do you use: the one on advent calendars, or the Church calendar?

By Sophie Shorland. Sophie is a writer, editor and historian with a PhD in all things early modern. She was recently shortlisted for the Tony Lothian prize, and you can find her counting down the days ‘til Christmas on twitter @sophie_shorland.