One poem written in 1892 by Henry Newbolt – Vitai Lampada – has always struck me as being one of the most powerful written in the English language. It goes as follows:

There’s a breathless hush in the Close to-night —

Ten to make and the match to win —

A bumping pitch and a blinding light,

An hour to play and the last man in.

And it’s not for the sake of a ribboned coat,

Or the selfish hope of a season’s fame,

But his Captain’s hand on his shoulder smote —

‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

The sand of the desert is sodden red, —

Red with the wreck of a square that broke; —

The Gatling’s jammed and the Colonel dead,

And the regiment blind with dust and smoke.

The river of death has brimmed his banks,

And England’s far, and Honour a name,

But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks:

‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

This is the word that year by year,

While in her place the School is set,

Every one of her sons must hear,

And none that hears it dare forget.

This they all with a joyful mind

Bear through life like a torch in flame,

And falling fling to the host behind —

‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

What is the poem about?

Well, essentially it was written about young men in late Victorian Britain who were told from a young age to adhere to certain sporting values i.e ‘’Play the game’’. An inherent belief in fairness, courage and duty (as is the case in many sports) was at the centre of this and it shows eerie parallels between the cricket field and the battlefield as it follows a young man from his time playing cricket at school (Clifton College in Bristol) to the battlefield in an unnamed part of the Empire.

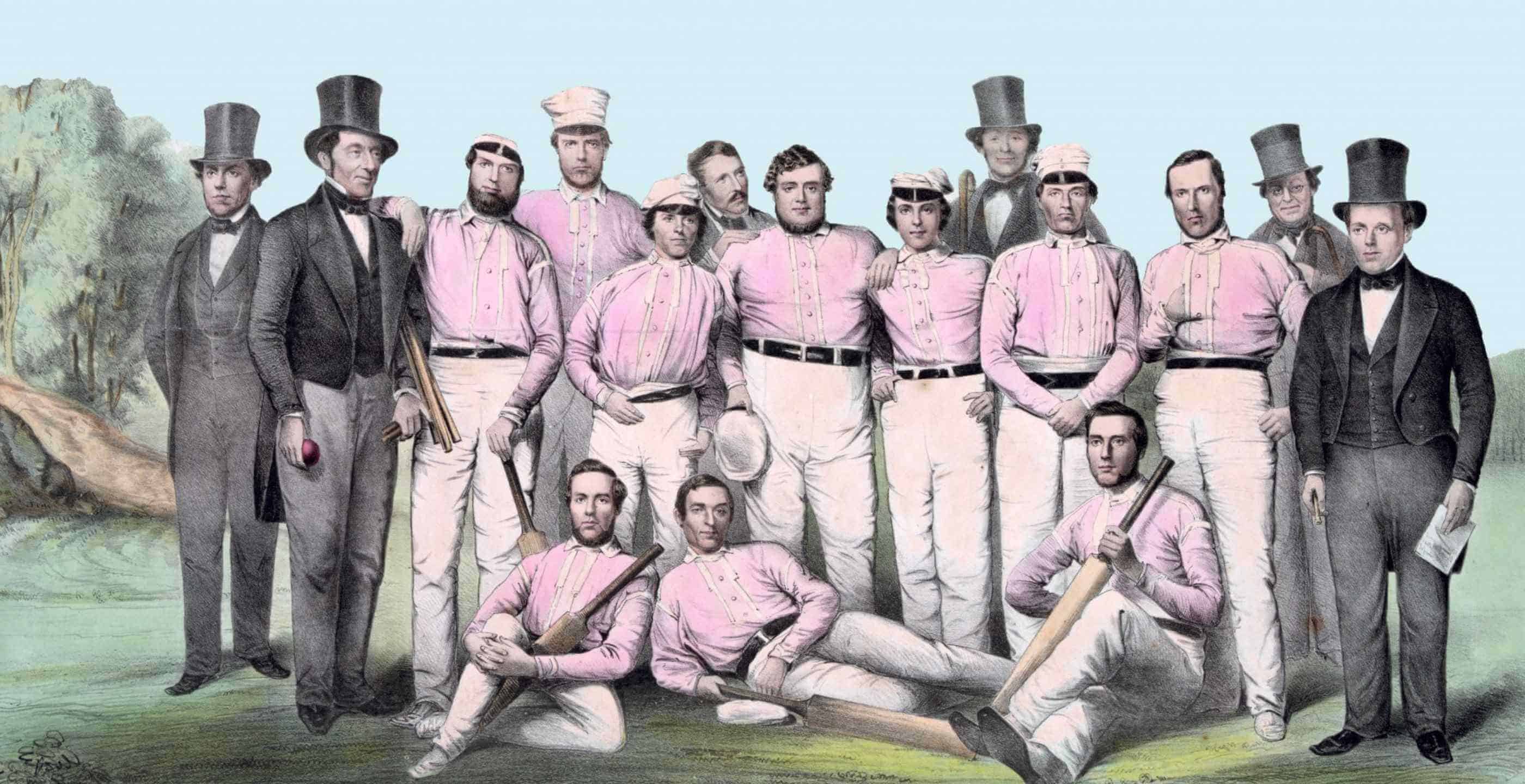

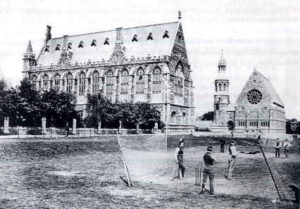

Clifton Collage Close, where the first stanza of the poem is set, with game of cricket in progress

Clifton Collage Close, where the first stanza of the poem is set, with game of cricket in progress

He ‘plays the game’ right even when his ‘captain’ (colonel) is dead and it seems he is facing death himself. He faces death with the same sporting ideals even when ‘England’s far and honour a name’.

Why is this such a powerful insight into the British psyche? It shows a heady idealism mixed with a fatalistic idea of duty, the combination of which is one which is heart-breaking when exercised far from home and away from those one loves. Above all, however it shows the idea of dying for something higher than one’s self, which is perhaps one of the ultimate existential questions for all human beings- for if you live and die by the rules of the game then nobody can deny you having lived in the right way.

Paradoxically this poem became even more popular during and after the First World War when it became apparent that this whole generation of young men, as well as this whole ethos died in the mud, blood and horror of the trenches of the First World War. What use was sporting fairness when millions die under machine gun fire, artillery shells and toxic gas from an unseen enemy? What dignity was there in cowering in a muddy ditch waiting for the end, crying and appreciating the beauty of life just before it is snatched away, like Prince Andrey’s haunting last true moments in Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’ at the Battle of Borodino?

A British army infantry square depicted during the Mahdist Wars at the end of the 19th century, perhaps inspiration for the second stanza of the poem

A British army infantry square depicted during the Mahdist Wars at the end of the 19th century, perhaps inspiration for the second stanza of the poem

It is very much the tragedy of a poem signalling the death throes of a different world. Perhaps this poem spoke to its readers of a lost world? A lost sense of innocence and duty where a young man could dream, before the crushing and suffocating reality of the modern world took it away so brutally. The painfully naïve hope of a young man looking to live in the right way compared to life’s brutal realities. Perhaps every person can relate to this in some way and this is what makes this poem so hauntingly powerful.

I suppose that is what we have now, in this time when we are feeling our way out of the Coronovirus crisis (in the UK at least). The world feels different, less innocent and a scarier place for many of us. We may not have lost millions in the trenches of the First World War but for many of us, everyday activities which we used to take for granted are now scary and unfamiliar, perhaps showing the symptoms of a worldwide episode of post-traumatic stress. Our naïve youth, much like those boys playing cricket has been shattered by a crisis not completely different from a war.

But perhaps there is hope in Vitai Lampada. For even if the ideals we and those boys lived by are not fully compatible with the new world we find ourselves in, we can still live by those ideals. We can believe in sporting fairness and playing the game even if the rules of the game seem unfair. We can still stand for something higher than ourselves. There is joy in the final four lines, joy of a life lived as well as possible, even if the circumstances of fate are against us. These final words are in my opinion one of the real gifts of British culture to the world:

This they all with a joyful mind

Bear through life like a torch in flame,

And falling fling to the host behind —

‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

Samuel Lister has a BA and MA in History from the University of Bristol and History and writing are his passions. He looks for the beauty and relevance of history to the world today and would love to offer something for others to think about or enjoy.