Many inventions throughout history have shaped the modern world in which we live. For many of us, our lifestyle and expectations have been shaped by processes, discoveries and accidents which happened many centuries ago.

Take for example the Wardian case, named after its inventor, Dr Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward. Dr Ward managed to grow a grass seedling in an air-tight jar, prompting him to fashion a receptacle in which to grow more plants. A small delight for a man passionate about botany in the nineteenth century who would go on to create an invention which would transform horticulture, global transportation and contribute to the formation of the British Empire.

This remarkable tale began in 1829 at a medical practice where Dr Ward, an enthusiastic naturalist, was keen to grow a variety of plants but always encountered difficulty due to the appalling conditions caused by the Industrial Revolution. An avid collector of herbarium, he was dismayed to discover that his attempts to grow ferns in his London garden were hindered by the nearby industrial pollution which led to acid rain and poor air quality.

Dr Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward

Dr Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward

Whilst his plants were failing to thrive in the adverse conditions of industrial Britain, Dr Ward continued his passion for botany indoors, adding to collections which he stored in air-tight glass jars, including keeping cocoons of moths.

He later observed by accident that one of the jars had a fern spore and grass seedling which had miraculously germinated whilst contained within the jar. Whilst the discovery was surprising, Dr Ward failed at the time to identify this development as particularly significant and would leave his natural wonder untouched for a further four years.

In this time, grass had actually been able to grow, however the neglect and unbroken seal of the jar eventually led to the casing becoming rusty, exposing the plants to bad air which caused them to die.

After witnessing this accidental scientific experiment, Dr Ward sought to find a way to mimic the qualities of the jar and create a vessel in which to grow plants. With the help of a carpenter, a glazed case was created, one that resulted in the successful growth of a fern.

This was quite remarkable. The Wardian case, as it became known was essentially a protective container, an early example of a terrarium which would revolutionise the world of botany as well as having enormous ramifications on international trade and competition.

Dr Ward was not alone in his creation of a terrarium; in fact ten years previously a fellow botanist called A.A Maconochie from Scotland had created a similar invention. Sadly for his compatriot he had failed to publish his findings, allowing Ward ten years later to receive the credit for such a useful invention.

Ward would subsequently publish a book on the matter entitled, “On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases” based on the various experiments he conducted.

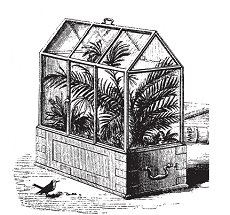

Wardian cases

Wardian cases

This invention would prove very useful in the coming century and its popularity would take on dizzying proportions.

The Wardian case’s principal use was for the transportation of plants which had previously proved extremely difficult in keeping the plants alive over long journeys. With the use of this new container, plants could be transported from far and exotic parts of the globe and survive a long journey back to Europe.

This was proved and supported by an experiment conducted by Ward’s plant supplier George Loddiges who sent his collection via ship, discovering on arrival that only one out of the twenty plants had survived. Meanwhile, with the aid of the Wardian case, nineteen out of twenty plants survived the journey.

The new invention thus acquired a commercial demand from wealthy landowners and businessmen who sought to cash in on the new found ease of transportation.

The Wardian Case helped to transport all variety of plants from ornamental to medicinal across the globe, protecting the young plants by putting them on the deck of the ship in order to get enough light.

Back in the homes of the elite of the United Kingdom and Europe, Wardian Cases became a popular fashion statement in which to display your wealth. Whilst the air outside swirled with pollution, the ferns and orchids thrived in their new homes.

Such was the scale of plant transportation in this time that barely a park in London did not contain a plant which had successfully navigated its treacherous journey from its native homeland in Dr Ward’s Case.

This was however just the beginning, as the case would help to facilitate the transportation of commodities across the globe, changing fortunes of nations and influencing the palates of a generation.

Those keen to use these new containers to advance their own business interests would prove highly successful in the coming years. One of these individuals included Robert Fortune who had been a curator at Chelsea Physics Garden and later would transform the fortunes of the British Empire as he smuggled tea out of China using the Wardian Case, transporting the plant to Assam.

On his first attempt he was not so successful, nevertheless he remained undeterred. Later, in 1849 he successfully shipped almost 20,000 tea plants out of China, taking the plants to British India, where a new thriving tea plantation could begin.

Tea plantation

Tea plantation

The successful mission had massive repercussions, enhancing the fortunes of the British Empire and breaking China’s monopoly on the commodity. Britain had previously been growing opium in India as early as 1757 which had until now been transported to China whilst Britain received tea in exchange. Nevertheless, the effects of the Opium Wars led the British to fear a legalisation of opium production which would impact their profits, thus necessitating a way of introducing their own tea trade straight out of their base in India.

Tea was not the only commodity which could now be easily shipped from port to port across the globe in the new container. In 1860, Clements Markham successfully used the case to smuggle the cinchona plant out of South America to India. A source of quinine, this was product which had important medicinal properties, as it could help prevent consumption (T.B.) as well as destroy the parasite which causes malaria.

Quinine would later find its use in tonic water, served best with a gin, however at the time, the prevention of malaria would prove crucial for a western population which found it difficult to assimilate into countries where tropical diseases proved deadly. The expansion of empire was thus facilitated by the use of quinine as global travel ambitions could now be realised.

Hevea seed

Hevea seed

Another vital commodity now in transit was the hevea seed, the seedlings of a rubber tree from Brazil which survived its journey to Sri Lanka and Malaya where it began a new rubber plantation in British imperial territory. As a result of the actions of Henry Wickham who purchased these seeds for a very reasonable price, Brazil’s monopoly over rubber production was now broken as Asian plantations quickly became more efficient.

This story became commonplace, largely as a result of the new opportunities the Wardian case presented, allowing seeds and plants to be taken from one side of the globe to the other. The British took advantage of this new invention, allowing plantations to flourish and non-native plants to grow in far-flung locations.

The new transportation helped cash crops to flourish also, impacting the consumer back in Europe who would now have access to a variety of different foods all year round. Coffee and sugar as well as fruits such as mango and bananas were now readily available for the first time.

The Wardian Case was not only transforming economies but also people’s tastes.

The effects of the Wardian Case permeated all aspects of life, contributing to changing appetites and leaving some reaping the rewards and leaving others reeling from the loss of revenue.

What began as a simple horticultural accident in Dr Ward’s home would transform into one of the most valuable inventions for a generation, defining the winners and losers of the nineteenth century and changing habits and diets forever.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.