On 11th November 1918, as bells rang out across Britain to mark cessation of the hostilities and carnage of the Great War, a telegram was delivered to the home of Mr and Mrs Tom Owen in Shrewsbury. Like hundreds of thousands of similar missives sent during the 1914-18 conflict, it spoke simply and starkly of death; the Owens’ eldest son, Wilfred, had been killed in action at Ors in France seven days prior to the Armistice. He was 25.

At the time of his death, Wilfred Owen was still to be recognised as one of our greatest war poets. Owen began writing poetry as a child, but it was during his treatment for shell-shock at Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh that Owen developed his technical and linguistic skills, crafting immortal verses to express visions of ghastly suffering, and the waste and futility of war. He was immeasurably influenced in both his poetry and his views of the war by his fellow-patient and writer, Siegfried Sassoon.

Owen enlisted in the British Army in 1915 and was commissioned to the Manchester Regiment the following year. His experiences on the front line in France in the early months of 1916 resulted in shell-shock, a condition then referred to as a form of ‘neurasthenia’, itself described more recently as chronic fatigue syndrome. Military and medical opinions at the time were divided as to whether shell-shock was a genuine reaction to the new horrors of mechanised, industrial-scale killing at the Western Front or cowardly malingering. However, the vast number of soldiers affected, especially after the battle of the Somme in 1916, required some form of help. The development of a Freudian approach to the psychological and physical effects of repressed traumatic memories coinciding with this type of casualty led to major advances in neuropsychiatric practice.

Craiglockhart Hydropathic

Craiglockhart, once a hydropathic spa hotel and now part of Napier University, is an imposing 19th century building set in acres of parkland. In 1916 it was requisitioned by the War Office as a hospital for shell-shocked officers and remained open for 28 months. A detailed assessment of the hospital’s admission and discharge records clarified the numbers of men treated and their destinations after treatment.

Initially, the approach to management of such patients seemed counter-intuitive: the men identified what they enjoyed and then were forced to do the opposite, for example outdoor activities for those with indoor, sedentary preferences. Results were poor. A change in Commandant early in 1917 resulted in a different regime. The medical staff included Dr William Rivers, who treated Sassoon, and Dr Arthur Brock, who treated Owen. Brock had managed neurasthenic patients before World War I and created ‘ergotherapy’, or ‘cure by functioning’, an active, work-based approach to therapy for soldiers, for example teaching in local schools or working on farms. Brock also encouraged patients, including Owen, and staff to write about their experiences for publication in the hospital’s magazine, ‘The Hydra’. The extraordinary Regeneration trilogy of novels by Pat Barker vividly dramatises these encounters and relationships.

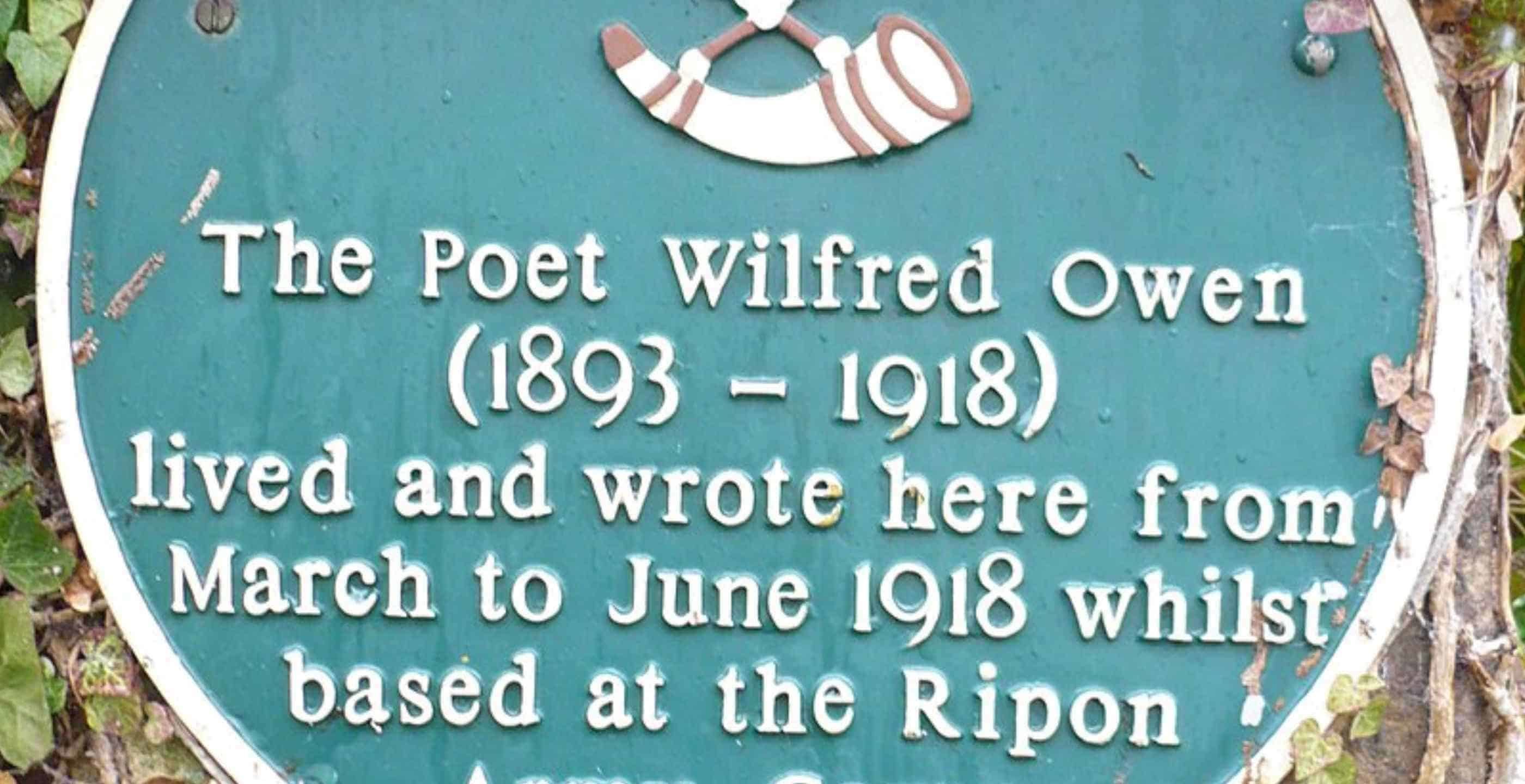

Owen arrived at Craiglockhart in June 1917. He met Sassoon in August and they formed a close friendship considered pivotal in Owen’s development as a poet. Sassoon had been sent to Craiglockhart after his written criticisms of the war became public; instead of a facing a court-martial, he was labelled as shell-shocked. In a letter written during his stay, Sassoon described Craiglockhart as ‘Dottyville’. His opinions profoundly affected Owen’s own beliefs and thus Owen’s writing.

Owen’s poetry was first published in ‘The Hydra’, which he edited while a patient. Few originals of this journal now exist and most are held by the University of Oxford, but in 2014 three editions were donated to Napier University by a relative of a former patient who had taken over from Owen as editor on his discharge from Craiglockhart in November 1917.

Siegfried Sassoon

After reserve duties in England, Owen was declared fit for service in June 1918. He and Sassoon met for the last time shortly before Owen returned to the Western Front in France in August. Owen was awarded a Military Cross for ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty on the Fonsomme Line in October. Sassoon did not learn of Owen’s death until months after the Armistice. In subsequent years, Sassoon’s promotion of Owen’s work helped established his posthumous reputation.

The headstone marking Owen’s grave in Ors Communal Cemetery bears as his epitaph a quotation chosen by his mother from one of his poems: “Shall life renew these bodies? Of a truth all death will he annul”. Owen is among the Great War poets commemorated in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner, and generations of schoolchildren have learned lines from ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ and ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’. The management of shell-shocked casualties in Edinburgh contributed to contemporary understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder. The tragedy of a wasted generation blazes in Owen’s words.

By Gillian Hill, freelance writer.