On 10th April 1829, William Booth was born in Nottingham. He would grow up to be an English Methodist preacher and go on to establish a group to help the poor which still survives today, the Salvation Army.

He was born in Sneiton, the second of five children to Samuel Booth and his wife Mary. Fortunately for young William, his father was relatively wealthy and was able to live comfortably and pay for his son’s education. Sadly, these circumstances did not last and in William’s early teenage years, his family descended into poverty, forcing him out of education and into an apprenticeship at a pawnbroker.

When he was around fifteen years old he attended chapel and immediately felt drawn to its message and subsequently converted, recording in his diary:

“God shall have all there is of William Booth”.

Whilst working as an apprentice, Booth made friends with Will Sansom who encouraged him to convert to Methodism. Over the years he read and educated himself, eventually becoming a local preacher alongside his friend Sansom who preached to the impoverished people of Nottingham.

Booth was already on a mission: he and his likeminded friends would visit the sick, hold open air meetings and sing songs, all of which would be later incorporated into the essence of the Salvation Army message.

After his apprenticeship ended, Booth found it difficult to find work and was forced to move south to London where eventually he found himself back at the pawnbrokers. In the meantime he continued to practise his faith and attempted to continue his lay preaching in the streets of London. However this proved more difficult than he had thought and he turned to open-air congregations on Kennington Common.

His passion for preaching was clear and in 1851 he joined the Reformers and the following year, on his birthday he made the decision to leave the pawnbrokers and dedicate himself to the cause at Binfield Chapel in Clapham.

At this moment his personal life began to thrive, as he met a woman who would dedicate herself to the same cause and remain by his side: Catherine Mumford. The two kindred spirits fell in love and became engaged for three years, in which time both William and Catherine would exchange several letters as he continued to work tirelessly for the church.

On 16th July 1855, the two were married at a South London Congregational chapel in a simple ceremony as they both wanted to devote their money to better causes.

As a married couple they would go on to have a large family, eight children in total, with two of their children following in their footsteps to become important figures in the Salvation Army.

By 1858 Booth was working as an ordained minister as part of the Methodist New Connexion movement and spent time travelling around the country spreading his message. However he soon grew tired of the restrictions imposed on him and subsequently resigned in 1861.

Nevertheless, Booth’s theological rigour and evangelistic campaign remained unchanged, leading him to return to London and conduct his own independent open air preaching from a tent in Whitechapel.

This dedication eventually evolved into the Christian Mission based in East London with Booth as its leader.

By 1865, he had established the Christian Mission which would form the basis for the Salvation Army, as he continued to develop the techniques and strategy for working with the poor. Over time, this campaign encompassed a social agenda which included providing food to the most vulnerable, housing and community-based action.

Whilst Booth’s religious message never faltered, his social mission continued to grow, involving practical grass-roots charity work which tackled those issues which had been festering for far too long. The taboos of poverty, homelessness and prostitution were addressed by his programme, organising accommodation for those sleeping on the streets and providing safe refuge for vulnerable fallen women.

In the coming years the Christian Mission had acquired a new name, one we are all familiar with – the Salvation Army. This renaming in 1878 occurred as Booth became well-known for his religious fervour and approach which had militaristic style organisation and principals.

With the increasing association of Booth and his evangelical team with the military, he very quickly became known as General Booth and in 1879 produced his own paper called the ‘War Cry’. Despite Booth’s growing public profile, he was still met with great hostility and opposition, so much so, a “Skeleton Army” was arranged in order to create chaos in his meetings. Booth and his followers were subjected in the course of their activities to numerous fines and even imprisonment.

Nevertheless, Booth persevered with a clear and simple message:

“We are a salvation people – this is our speciality – getting saved and keeping saved, and then getting somebody else saved”.

With his wife working by his side, the Salvation Army grew in numbers, with many converted from the working classes adorned in military style uniforms with a religious message in tow.

Many of the converts included those who would be otherwise unwelcome in respectable society such as prostitutes, alcoholics, drug addicts and the most deprived in society.

Booth and his Army grew in spite of opposition and by the 1890s, he had acquired great status and awareness for his cause.

The Salvation Army had grown in popularity and extended far and wide, across continents to as far as the United States, Australia and India.

Sadly, in October 1890 he was to suffer a great bereavement as his loyal partner, friend and wife passed away from cancer, leaving William in a state of grief.

Whilst he felt a great loss in his life, the everyday administration of the Salvation Army was a family affair and his eldest son Bramwell Booth would end up as a successor to his father.

Such organisation was required as the Army, at the time of Catherine’s death, had great numbers of recruits amounting to almost 100,000 people in Britain.

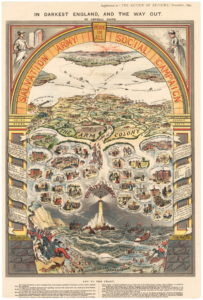

Undeterred despite his personal setback, Booth went on to publish a social manifesto entitled, “In Darkest England and the Way Out”.

Within this publication, Booth, with the assistance of William Thomas Stead, proposed a solution to poverty through the provision of homes for the homeless, safe houses for prostitutes, legal aid given to those who could not afford it, hostels, alcoholism support and employment centres.

These were revolutionary ideas with far-reaching consequences and soon garnered a great deal of support from the public. With funding assistance, many of his ideas were executed and fulfilled.

At this point, a huge shift in public opinion occurred, with so much initial opposition to the Salvation Army and his mission giving way to support and sympathy. With this growing wave of encouragement and backing, more and more tangible results could be produced.

So much so that in 1902, an invitation from King Edward VII was extended to William Booth to attend the coronation ceremony, marking a real awareness and recognition for the good work Booth and his team were accomplishing.

By the early 1900s aging William Booth was still willing to embrace new ideas and change, particularly the advent of new and exciting technology which involved him participating in a motor tour.

He also travelled extensively as far as Australasia and even to the Middle East where he visited the Holy Land.

Upon his return to England the now highly esteemed General Booth was well-received in the towns and cities he visited and was given an honorary doctorate from Oxford University.

In his final years, despite his failing health, he returned to preaching and left the Salvation Army in the care of his son.

On 20th August 1912, the General drew his last breath, leaving behind a substantial legacy, both religious and social.

In his memory a public memorial service was arranged, attended by around 35,000 people, including representatives of the King and Queen who wanted to pay their respects. Finally, on 29th August he was laid to rest, a funeral which attracted vast crowds of mourners who listed attentively to the service as London’s streets stood still.

The General had left behind an army, an army who would in his absence continue his good work with a social conscience that continues to this day around the world.

“The old warrior finally laid down his sword”.

His fight was over, but the war against social injustice, poverty and neglect would continue.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.