“It’s never too late to come back”

In 1940, the part of World War Two that became known as the ‘Struggle for North Africa’ began. This Desert War, or Western Desert Campaign (as it was also known) was to last three long years, and took place in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia. It became the first major allied victory in the war, due in no small part to the allied air forces.

It was in this Western Desert Campaign in 1941 that the ‘Late Arrivals Club’ was born. It was started by British servicemen at the time, and was also known as the ‘Winged Boot’ or ‘Flying Boot’ Club. During this conflict many airmen were shot down, bailed out of aircraft, or crash landed deep in the desert, and often behind enemy lines.

Spitfire on a landing ground in the Western Desert.

Spitfire on a landing ground in the Western Desert.

If these men made it back to their base camps, it was likely a long and arduous journey. However, when they did make it back they were known as ‘’corps d’lite’ or ‘late arrivals’. They were coming home so much later than those pilots who had managed to return to their bases in their aircraft. Some had been missing for some weeks before they made it back to their camps. As more and more of these situations occurred and more and more airmen arrived back late, the mythology surrounding their experiences grew and an informal club was formed.

A silver badge depicting a boot with wings extending from the side was designed in their honour by RAF Wing Commander George W. Houghton. The badges were (appropriately) sand cast in silver which were made in Cairo. Each member of the club was given their badge, and a certificate detailing what made them eligible for membership. The certificate always contained the words, ‘it is never too late to come back’ which became the club’s motto. The badges were to be worn on the left-breast of the aircrews’ flying suits. Estimates vary, but in the three-year conflict around 500 of these badges were given out to military personnel who were in the British and Commonwealth services.

The conditions for these airmen who were shot down, crash landed or bailed out into the Western Desert would have been almost unbearable. Scorching days followed by freezing nights, sand storms, flies and locusts, no water except what they could salvage and carry from their stricken aircraft and the ever-present danger of being discovered by the enemy. Additionally, RAF aircrew uniform at the time was abysmally suited to the desert during the day, but at least the Irving jacket and fur-lined boots would keep them warm overnight.

In many cases it was due to the hospitality and kindness of local Arabs who hid the allied airmen and provided them with water and supplies, that they were able to make it back at all. Many of these airmen’s diaries contain stories of close shaves with the enemy and having to do everything from hiding under rugs in Bedouin tents, dressing as Arabs themselves to even, in extremis, pretending to be members of enemy forces. All of these various deceptions were necessary simply for them to survive long enough to make it back over the enemy lines and back to safety. There are records of some airmen coming down as far as 650 miles into enemy territory and having to make the arduous journey back. There is no doubt that many of these airmen owe their lives to the kindness and hospitality of the locals who helped hide them, and in some cases even guided them back to camp.

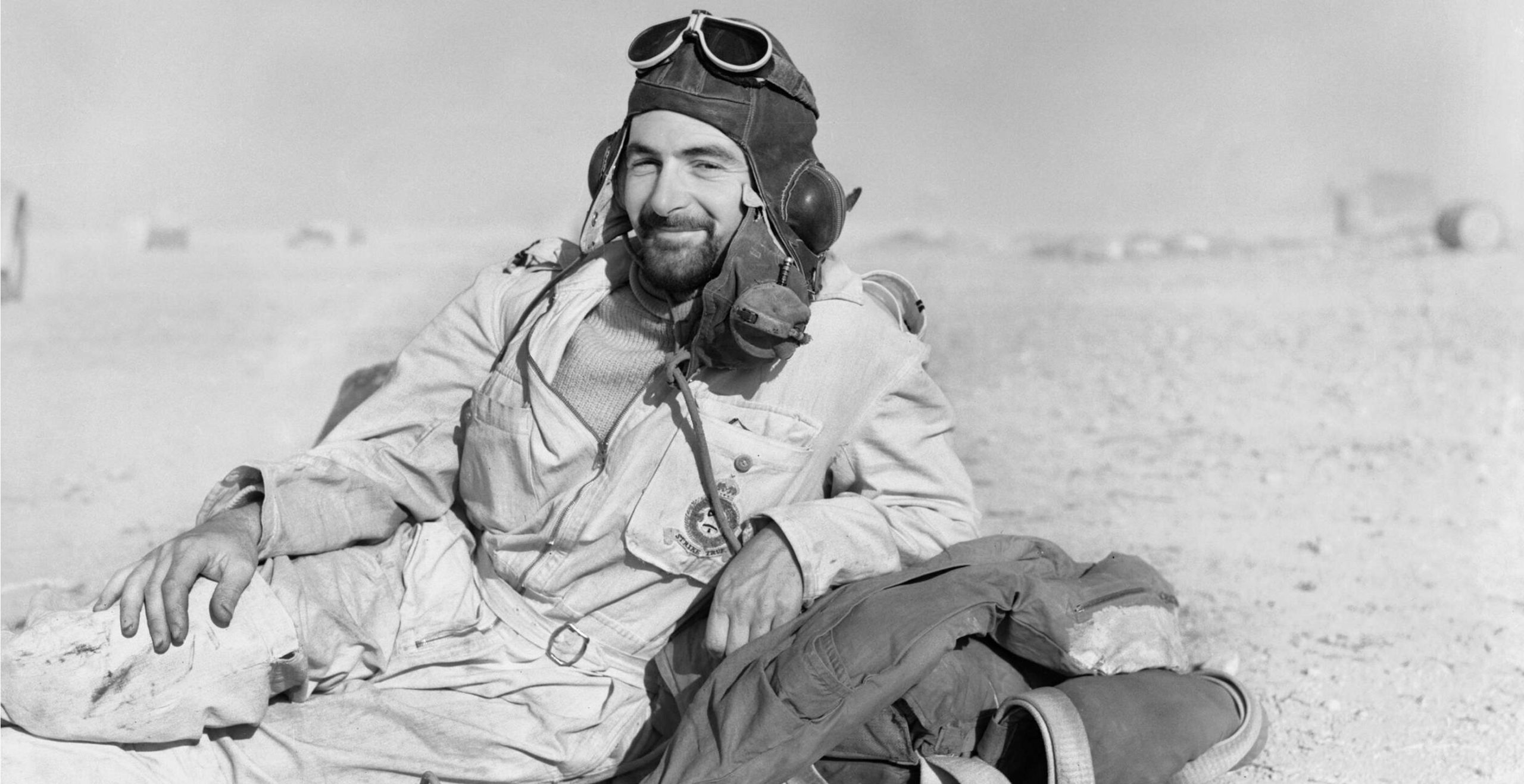

Flying Officer E. M. Mason of No. 274 Squadron RAF Detachment relaxes on his parachute after hitchhiking by air and road back to the Detachment’s base at Gazala, Libya, following an aerial combat 10 miles west of Martuba.

Flying Officer E. M. Mason of No. 274 Squadron RAF Detachment relaxes on his parachute after hitchhiking by air and road back to the Detachment’s base at Gazala, Libya, following an aerial combat 10 miles west of Martuba.

Membership to the club was exclusive to the Royal Air Force or colonial squadrons who fought in the Western Desert campaign. However, in 1943 some American airmen, who had fought in the European theatre and who were also shot down behind enemy lines, started to adopt the same symbol. Some had walked hundreds of miles behind enemy lines in order to get back to allied territory, and many of them were helped by the local resistance movements. Because they had managed to evade capture, they were known as evaders and the Winged Boot also became a symbol of this type of evasion. When these US aircrew made it back to the UK, and after they had been debriefed by RAF intelligence, they would often head to Hobson and Sons in London to get their ‘Winged Boot’ badges made. As they were never ‘official’ not having fought in the Western Desert, they wore their badges under their left-handed lapel.

Although the club is no longer active, and is definitely the shortest lived of the World War Two Air Clubs (others include: The Caterpillar Club, The Guinea Pig Club and The Goldfish Club) its spirit lives on in the Air Force Escape and Evasion Society. This is an American society that was formed in June 1964. They adopted the Winged Boot as there was no more apposite symbol than that which honoured those first escapees through enemy territory who were helped by resistance fighters. The AFEES is a society that encourages airmen to keep in touch with those resistance organisations and individuals that helped save their lives on their long walks to safety. Their motto is, ‘we will never forget’.

“Our organization perpetuates the close bond that exists between airmen forced down and the Resistance people who made their evasion possible at great risk to themselves and their families.” – Past AFEES President Larry Grauerholz.

The AFEES in turn, was inspired by The Royal Air Forces Escaping Society. This society was set up in 1945 and disbanded in 1995. Its purpose was to financially support those people still living, or relatives of those who lost their lives, who had helped members of the RAF escape and evade capture during World War Two. The Royal Air Force Escaping Society’s motto was ‘Solvitur Ambulando’, ‘Saved by Walking’.

Whether traipsing through an enormous expanse of enemy occupied desert, or being aided in escape by the European resistance, those brave aircrew who were ‘saved by walking’ truly did show how it was ‘never too late to come back’ and consequently, ‘we will never forget’ them and everything they did during the Second World War.

By Terry MacEwen, Freelance Writer.

Published: 24th May, 2022.