The ancient windmill at Chesterton, in Warwickshire, is one of the most well-known and admired landmarks in the Heart of England.

Though the countryside is dotted with other survivors from our rural past, none can match the elegance and panache of Sir Edward Peyto’s creation, sited on a hill overlooking the Fosse Way – the old Roman road which still serves as an important artery for travellers through central England.

The mill was commissioned by Peyto as Lord of the local Manor in 1632 and designed by, or inspired by, the influential architect Inigo Jones.

Though it was built as a working mill, Sir Edward cannot have been solely interested in its functional purpose, since he went to extravagant lengths and great expense to create something that was unique, almost revolutionary in its design.

Chesterton Windmill, Warwickshire, England

Chesterton Windmill, Warwickshire, England

To travellers on the Fosse Way today, Chesterton windmill catches the eye, but looks much like an elegant folly. At the time it was built the effect on travellers of the new structure would have been more dramatic. In the context of 17th century rural England, the windmill would have been a stunning and towering edifice, a striking statement of wealth, power and beauty. A vanity project in all probability.

In that sense it should not be a surprise that some have claimed Chesterton to be the model for a strange stone structure in Rhode Island, USA, which has intrigued historians for centuries.

Such a level of interest in the Newport Tower is surprising, given its modest size and its location, tucked away in a town park. Yet America is a land with few ancient mysteries; and the structure of the Tower is certainly at odds within anything around it. Like other places in New England, Newport has many surviving reminders of its colonial past – elegant and colourful timber-framed buildings. These have nothing in common with the rough stone tower.

Newport Tower, Rhode Island, USA

Newport Tower, Rhode Island, USA

Inevitably it has been the object of many conflicting claims about its origins and purpose.

In 1841 Danish antiquarian Charles Christian Rafn claimed that the Vikings had settled around Narraganset Bay (now Rhode Island) and that they had built the stone tower. Rafn’s claim fired something in the public imagination and the idea of the “Viking Tower” rapidly took off. Visitors flocked to see it and Longfellow immortalised it in his poem “The Skeleton in Armour.”

Not everyone in Newport was impressed, however, and in an article published ten years later the Reverend Charles T. Brooks rubbished the Viking theory. Brooks claimed that he had researched the family background of Newport’s’ first Governor, a man named Benedict Arnold. He found, he said, that Arnold had emigrated to America as a boy with his family who came from Leamington in Warwickshire, England. On his death in 1678 Arnold had referred to the tower in his will as a “stone-built windmill.” The same document also referred to a portion of Arnold’s Rhode Island estate known as “Lemington Farm.” Given these domestic links to Warwickshire, the Governor must have had the tower built as a windmill following the design of the Chesterton windmill, with which he would undoubtedly have been familiar.

Brooks’s intervention seemed to have quashed the Viking Tower story, but if he thought his more prosaic version of the truth would be the final word, he was sorely mistaken. As the twentieth century progressed, not only did other, more remarkable claims emerge, but his own research was badly undermined. Before long, Brooks’s own version would itself be cruelly dismissed as the “Warwickshire hoax.”

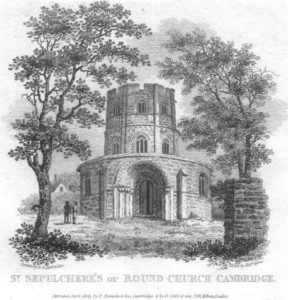

During the last one hundred years, claims have been advanced that the Tower was built by, among others, Portuguese and Chinese explorers. Architectural links have also been argued between the Tower and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Cambridge, a building long associated with the Knights Templar.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Cambridge

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Cambridge

Most recently Newport man Jim Egan has published extensive research from which he concludes that the tower was built by an advance party of Englishmen on behalf of a secret mission to colonise America during the reign of Elizabeth I; and that the tower was designed by Elizabeth’s magus, John Dee, as an astronomical timepiece.

All these versions are tantalising but have faced an uphill battle to be accepted by mainstream historians.

The Tower is now owned by Newport City Council who in 2016 commissioned a study by archaeological specialists which followed earlier investigative digs and carbon-fibre dating of the mortar. All of this pointed to the conclusion that the Tower was between 1650 and 1677, a timescale entirely consistent with the Colonial windmill theory.

But the connection with Benedict Arnold of Leamington Spa was dealt a mortal blow as a result of new extensive research carried out by American Fred A. Arnold.

This proved that Benedict’s family came not from Warwickshire but the town of Ilchester in Somerset. In 1635, when Benedict was nineteen, he emigrated with his parents to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the New World, later moving to Rhode Island. His use of the name Lemington for his farm probably reflected the fact that he went to school in Limington, one mile from Ilchester, and thus it has no connection with Leamington Spa in Warwickshire.

However, it is not necessary to rule out Governor Arnold as the brains behind the tower. He may not have come from Warwickshire, but his home town of Ilchester also sits astride the Fosse Way. It is possible that he had travelled with his father to Leicester or Lincoln for some purpose and seen the Chesterton windmill with his own eyes.

Indeed, any traveller along the Fosse Way in those early years would almost certainly have retained a clear image of Chesterton in their memory. Thus, there is every possibility that among the English settlers in the embryonic Rhode Island colony, there was a stonemason or builder who conceived the idea of creating a windmill like Chesterton.

The overwhelming balance of evidence points to the Tower being a windmill, modelled on Chesterton, and built in the early days of the Colony. But as long as this evidence is not completely conclusive, there will always be room for alternative theories to gain support.

Author’s Note: The Chesterton windmill is situated just off the B4555, Fosse Way, in the north of the District of Stratford upon Avon, approximately 7 miles from Leamington Spa. There are numerous tourist attractions nearby, including Warwick Castle and Shakespeare’s Stratford.

By Richard Eggington. A former Town Clerk of Stratford upon Avon and charity chief executive, Richard has over 20 years experience writing and lecturing on American Colonial and Western history.