“I never ride in from Hyde Park Corner… but the ghosts of an army of horsemen ride with me,” wrote Roland Collins in 1967. If the ghosts of all those who have ridden or driven in Hyde Park were visible, it would create the ultimate pageant of British history.

It would include many monarchs, including Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Charles II and Victoria. The Duke of Wellington would be in attendance too, along with members of the “upper 10,000”, or “upper 10”, Britain’s aristocracy across the centuries. From the 17th century would appear Cromwell, who was involved in an eye-watering incident there in the days of the Commonwealth, and Samuel Pepys, no doubt keeping an eye out for pretty women and grumbling about the cost of maintaining a carriage.

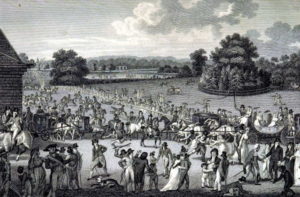

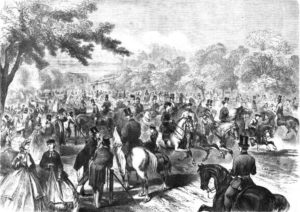

The Entrance to Hyde Park on Sunday, 1804

The Entrance to Hyde Park on Sunday, 1804

In 1809, the Persian ambassador, Mirza Abul Hassan Khan, would have drawn the eye in his traditional riding dress, out in the park on horseback even in the gloomy January weather. Not to mention those bad boys of the late 18th century, the Macaronis, astride their pretty ponies with sweeping manes and tails. In the 1860s Hyde Park witnessed the phenomenal success of the “pretty horsebreakers” such as Skittles.

The democratisation of Hyde Park certainly didn’t put off Britain’s royals though, and George V rode regularly in the park. In the 1930s, the whole Kennedy family used to ride out in Rotten Row when Joseph Kennedy was the US Ambassador to the UK.

The history of Hyde Park is traceable to early medieval times, with the formation of the Manor of Eia. Because of its proximity to the Palace of Whitehall, it was inevitable that there would be royal interest in the land which is now Hyde Park, and Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries meant he could quickly grab it for himself from the church, to which it had been gifted by Geoffrey de Mandeville, or Mainville.

As well as being a hunting park for the king, the newly-created royal park, from now on known as Hyde Park, was an important source of springs that provided the capital with drinking water. The Tyburn brook which ran along one side gave a good fresh supply and also famously provided the location and the name of London’s gallows. Many of the riders who crossed the land throughout the centuries would be on their way to gawk at public executions on the spot where Marble Arch now stands.

However, as Mrs Alec Tweedie, early 20th century author of “Hyde Park: its History and Romance” points out, “More cheerful things than hunting and death appear in the days of Henry VIII”. The Park was also used by the Tudors for the established royal activities of canoodling and feasting, with a handy banqueting house constructed to carry out both in the proper fashion.

One description of the high-maintenance Anne Boleyn describes how she made her way to the abbey across the park in an upholstered white and gold chariot, the vehicle of choice for the elite in the days before the creation of the coach. It was drawn by white palfreys, and the gorgeously-dressed queen was accompanied by “seven great ladies” (it must have been all the feasting) dressed in crimson velvet and cloth-of-gold, and all mounted on palfreys.

Elizabeth I used Hyde Park as a reviewing space for mounted troops as well as carrying on the hunting tradition. Coaches began to be used during her reign and their use proliferated during the reign of James VI/I. The first public vehicles for hire – hackneys – were established at this time too. Hyde Park would soon become the place for the elite to display themselves in their vehicles. It’s likely that horse racing in Hyde Park began under James I as well, and perhaps surprisingly, coach racing appears to have been popular during the Commonwealth.

Map of Hyde Park, 1833. “The King’s Private Road” is Rotten Row.

May Day had always been a day of celebration for merry old England, though it seems odd that it didn’t entirely fall under the prohibitive axe of the Puritans, given the day’s reputation for louche behaviour. In fact, May Day in Hyde Park under Cromwell and crew seems to have been a lively affair, with plenty of coaches turning out and their drivers chasing each other all over the park.

On another occasion, Cromwell is said to have been angered by the slow pace of his fine Friesian horses, a recent gift from the Duke of Holstein. Seizing the reins for himself (how Cromwellian) he began to whip the horses, who panicked and ran off. The Lord Protector made an unplanned exit from the driving seat, entangling himself in the harness and causing his pistol to go off unexpectedly in his pocket. He escaped with bruises. Unfortunately, the thoughts of his coachman have not been recorded.

The atmosphere in Hyde Park grew even merrier under Charles II, who reintroduced such crowd-pleasers as racing as well as a new novelty, Riding in the Ring. This was an enclosed circular space around which coaches drove in two directions, first one way and then the other, creating the opportunity for their occupants to nod, smile and flirt with each other as they passed. A typically Stuart speed-dating event, in other words.

This was probably the point at which Hyde Park fully established its reputation as the place to see and be seen, whether on horseback or in a carriage. It continued to be used for military displays too. Joyce Bellamy recounts in her book “Hyde Park for Horsemanship” that in 1682 it provided the setting for the Ambassador of the Sultan of Morocco to organise a “Fantasia”, the dramatic display of arms and horsemanship that is still immensely popular in North Africa.

Under Charles II, women’s riding outfits had begun to echo those of the men, with deep-skirted coats and plumed riding hats. Riding on horseback would become ever more popular among the women of the elite. When the coach road installed across the park under William III was abandoned due to the building of another road further north, horse riders claimed the route for themselves and Rotten Row was created.

It’s suggested that the name either comes from “Route de Roi”, the King’s Way; or possibly rotteran, a military gathering. It was certainly in use from the late 18th century, and that’s how it was known in in the 19th century, and is still known today. Crammed with fashionable horse riders (only the monarch is allowed to drive a carriage along Rotten Row), it became one of the daily events of the summer season. The Persian ambassador Mirza Abul Hassan Khan estimated that even in December he saw 100,000 men and women walking and riding in the park in 1809.

In her memoir of her husband, the novelist John Buchan, Lady Tweedsmuir claimed that her ancestor Mary Stuart-Wortley, nicknamed Jack, was “the first women to ride even modestly on a side-saddle in Rotten Row”. By the late 19th century, the arrival of the “pretty horsebreakers” and ever-increasing numbers of wealthy middle class riders meant that there was no longer any pretence that the daily display on horseback was the sole domain of the aristocracy.

Satire on the “monstrosities” of fashion of the year 1822. It shows the promenade of fashionable people in Hyde Park with the Achilles statue in the background. By George Cruikshank, 1822

Satire on the “monstrosities” of fashion of the year 1822. It shows the promenade of fashionable people in Hyde Park with the Achilles statue in the background. By George Cruikshank, 1822

Riders often hired horses from nearby livery yards. The infamous naked statue of Achilles, paid for by public subscription to commemorate the victories of the Duke of Wellington, was one of the gathering points. A whole school of horsemanship known as “Park Riding” grew up, with its own etiquette, dress and fashion in horses. The “Four-in-Hand Club” meanwhile maintained the carriage tradition.

During the 20th century, many of the surviving livery yards became riding schools, of which the most famous was probably the Cadogan Riding School, owned by the Smith family. Horace Smith taught several members of the royal family to ride, including Queen Elizabeth II when she was a child. The Civil Service and BBC had riding clubs that used stables near Hyde Park.

Today, Rotten Row is still used for exercising horses of the Household Cavalry. The Royal Park Shires can sometimes be seen working there too. There are still riding schools nearby, though they are few in number and keeping horses in central London is an expensive business. However, as Joyce Bellamy points out, “The Row alone among public riding areas has enjoyed a special status as a London landmark”, and that continues even though most of the horses are gone.

For more on the Cadogan Riding School and the Smith family, see https://booksandmud.blogspot.com/2011/04/more-on-cadogan-riding-school_22.html

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.