The name of Newgate is notorious in the annals of London’s history. Developing out of a collection of cells in the old City Walls to the west (above the ‘New Gate’), it was begun in 1188 during the reign of Henry II to hold prisoners prior to their trial before the Royal Judges. The name passed into infamy as a byword for despair; an oubliette from which the hangman’s rope was often the only way out.

Robbery, theft, non-payment of debts; all were crimes which could land you inside as a succession of famous prisoners, from Ben Johnson to Casanova, could testify. The jail was located very near to the Smith Field just beyond the city walls, a place where cattle were slaughtered during market days and the condemned were hanged or burnt in displays of public execution.

It comes as no surprise that Newgate Prison, the decaying heart of the medieval city, has its fair share of grim and gruesome tales and one such tells of a severe famine that gripped the land during the reign of Henry III. It was said that conditions inside became so desperate that prisoners found themselves driven to cannibalism to stay alive. The story goes that a scholar was incarcerated amongst the despairing inmates, who wasted little time in overpowering and then devouring the helpless man.

But this turned out to be a mistake, for the scholar had been imprisoned for crimes of witchcraft against the king and the state. Sure enough, so the story goes, his death was followed by the appearance of a monstrous coal-black dog who stalked the guilty prisoners within the slimy dark of the prison, killing each until a small few managed to escape, driven mad with fear. The dog’s work however was not yet done; the beast hunted down each man, and thus revenged its master from beyond the grave.

Drawing of the Black Dog of Newgate, 1638

Drawing of the Black Dog of Newgate, 1638

Perhaps this evil spirit was a manifestation of the brutal conditions inside, a tale told to children as a warning of what would happen should they find themselves on the wrong side of the law. But petty crime was a way of life for many, who often faced a choice between stealing and starving. The celebrated thief Jack Sheppard was one such, and his succession of daring escapes from various prisons turned him into a folk hero for the working classes.

He famously managed to break out of jail four times, including twice from Newgate itself. The first involved loosening an iron bar in the window, lowering himself to the ground with a knotted sheet and then escaping in women’s clothes. The second time he found himself at His Britannic Majesty’s pleasure, his escape was even more daring. He climbed up the chimney from his cell into the room above, and then broke through six doors to lead him into the prison chapel from where he found the roof. Using nothing more than a blanket, he made his way across to a neighbouring building, broke quietly into the property, went down the stairs and let himself out of the back door into the street – and all without a sound to wake the neighbours.

When it became known, even Daniel Defoe (himself a former guest of Newgate) was amazed, and wrote an account of the feat. Sadly for Sheppard, his next stay in Newgate (for it seems he could not abandon his thieving ways) was to be his last. He was carted away to the gallows at Tyburn and hanged on 16 November 1724.

Jack Sheppard in Newgate Prison

Jack Sheppard in Newgate Prison

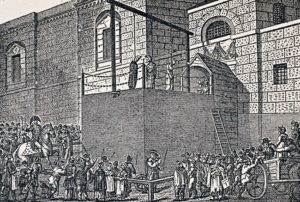

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, all public executions were moved to Newgate and this coincided with a greater use of the death penalty, even for crimes previously considered too minor to merit the ultimate sentence. The so-called ‘Bloody Code’ created over two hundred offences that were now punishable by death, and this would not be relaxed until the 1820s, though transportation to the colonies was very often used for a variety of crimes.

Newgate became a sea of spectators on execution days, with a grand stage erected on what is now Old Bailey, all the better to give the huge crowds the best view possible. If you had the money, the Magpie and Stump public house (conveniently located directly opposite the bulk of the prison) would happily rent out an upstairs room and provide a good breakfast. Thus, as the condemned were allowed a tot of rum before the final journey along Dead Man’s Walk to the scaffold, the affluent could raise a glass of a better vintage as they watched the hangman go about his work.

Public executions were discontinued in the 1860s, and were moved inside the yard of the prison itself. However, you will still find the Magpie and Stump in its old location, with a not too dissimilar clientele; detectives and lawyers rub shoulders with journalists as they await the verdicts from the myriad courtrooms inside Old Bailey, the throng of the baying crowd replaced by the scrum of television cameras.

Public hanging outside Newgate, early 1800s

Public hanging outside Newgate, early 1800s

Newgate Prison was finally demolished in 1904, ending its seven hundred year reign as the blackest hole in London. But take a walk along Newgate Street and you will see the old stones of the former prison now supporting the modern walls of the Central Criminal Court. London has a way of recycling its past. If you feel inclined, take a short walk across the road to where the church of St Sepulchre stands watching over this ancient part of the city. Walk inside and down the nave, and there you will find in a glass case the old Newgate execution bell. It was rung during the night prior to an execution – an alarm which ended for all in a permanent sleep.

By Edward Bradshaw. Ed studied English at Royal Holloway, University of London, and has a keen interest in all things to do with British History, having worked in the arts and heritage sector for many years. He is also a professional freelance guide for the City of London Corporation and a member of the City Guide Lecturers’ Association. Ed is also a keen writer with stage and radio credits, and is currently working on his first novel.