Totnes Castle, whilst not the largest nor most imposing example of medieval masonry or castle building, is a fantastic site and historical landmark. It is one of the earliest and best preserved examples of Norman motte and bailey earthworks still surviving, and the largest in Devon (almost double the size of Plympton and Barnstable). The later medieval keep is still perched upon the towering man-made mound, or ‘motte’, of earth and rock designed to impress Norman authority upon the Anglo-Saxon townsfolk of Totnes, giving visitors today an incredible view of Totnes, the River Dart and Dartmoor. The ‘bailey’ refers to the large courtyard, which was originally marked by its surrounding moat and timber palisade, but is now a stone walled courtyard.

The term ‘motte and bailey’ is as symbolic of the Norman invasion as the castle itself. Both ‘motte’ and ‘bailey’ derive from Old French; ‘motte’ meaning ‘turfy’ and ‘bailey’ or ‘baille’ meaning low yard. It is symbolic because the Norman invasion was not only the imposition of a new monarch, but was also a cultural invasion. The granting of estates to William the Conqueror’s supporters meant that within a couple of generations, the aristocratic elite were French-speaking, with Old English being relegated to the language of the lower classes.

Totnes Castle – the bailey

Totnes Castle – the bailey

The history of Totnes Castle is a wonderful demonstration of the broader history of castle building in England. Castles were yet another French fashion brought to us via the 1066 conquest.

The old adage that the Normans introduced castles to Britain is not necessarily the case; Anglo-Saxon and Roman Britain had made use of earlier Iron Age hillforts, raised earthworks for fortified settlements, particularly in the wake of Viking invasions. The widespread strategic castle building, which has left some of the best medieval landmarks, was an innovation of the Norman invaders. They introduced the motte-and-bailey castle as a (relatively!) speedy way to enforce their leadership. Initially Totnes Castle was built from timber as a cheap and quick resource. However fortunately for us, the site was rebuilt in stone in the late twelfth century and refortified again in 1326.

Totnes Castle – the keep

Totnes Castle – the keep

Totnes Castle was built as a means to subdue the bustling Anglo-Saxon town. Whilst many Anglo-Saxons post conquest did indeed ‘break bread’ with the invaders, many areas of England saw rebellion, as happened in the South West. The Norman army made their way to the Devon quickly after the 1066 invasion, in December 1067 – March 1068. Many Anglo-Saxons in Devon and Cornwall refused to swear an oath of fealty to William the Conqueror and rallied in Exeter in 1068 in support of Harold Godwinson’s family’s claim to the throne. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records ‘he [William] marched to Devonshire, and beset the city of Exeter eighteen days.’ Once this siege was broken the Norman army swept through Devon and Cornwall, including building fortifications in the wealthy town of Totnes.

Totnes Castle

Totnes Castle

The castle and barony of Totnes was initially granted to Judhael de Totnes, a supporter of William the Conqueror from Brittany. In return for his support, Judhael was granted Totnes as well as other estates in Devon, including Barnstable, recorded in the Domesday survey in 1086. Whilst in Totnes he founded a priory, recorded by a foundation charter of 1087 archives. Unfortunately the priory no longer stands, however the fifteenth century Church of St Mary sits on the site of the priory of the same name. Unfortunately Judhael’s time in Totnes was short lived as on the ascension to the throne of William’s son, William II, he was ousted for his support of the Kings brother and the barony was given to the King’s ally Roger de Nonant. It stayed with the de Nonant family until the late twelfth century, when it was claimed by the de Braose family, distant descendants of Judhael. The castle then remained hereditary, passing on to de Cantilupe and later de la Zouche families through ties of marriage. However in 1485, after the Battle of Bosworth and ascension of Henry VII to the throne, the lands were granted to Richard Edgcombe of Totnes. The previous owners, the de la Zouches, had supported the Yorkist cause and thus were ousted in favour of the Lancastrian Edgcombe. In the 16th century the Edgcombes sold it to the Seymour family, later dukes of Somerset, with whom it remains to this day.

Totnes was a prestigious market town with easy river access at the time of the Norman Conquest, and the presence of the castle could demonstrate that the Anglo Saxons of this area were considered a real threat to William. The castle’s prospects didn’t fair as well as the town’s, and by the end of the medieval period it was largely out of use and the lodgings once situated within the

bailey were in ruins. Fortunately the castle keep and wall were maintained, despite the interior buildings falling into disrepair, hence it’s survival today. The keep itself was used once again during the Civil War (1642-46), occupied by royalist, ‘cavalier’ forces, but was gutted in 1645 by the parliamentarian ‘New Model Army’ which was led by Sir Thomas Fairfax as he headed to Dartmouth and southwards.

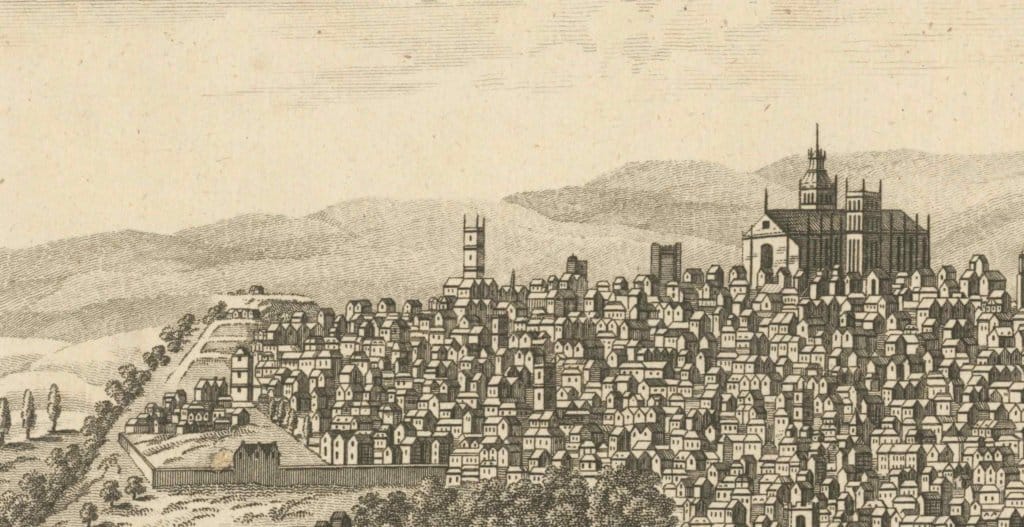

View of the town from the castle

View of the town from the castle

Post Civil War, the Castle was sold by the Seymours to Bogan of Gatcombe, and again the site fell in to ruin. However in 1764 it was purchased by Edward Seymour, the 9th Duke of Somerset whose family also owned nearby Berry Pomeroy, also by this point in ruin, bringing the site back in to the family. The site was well maintained by the Duchy, and in the 1920s and 30s even had a tennis court and tea rooms open to visitors! In 1947 the Duke granted stewardship of the site to the Ministry of Works who, in 1984, became English Heritage who care for it to this day.

Inside Totnes Castle:

– There are 34 merlons on top of the castle. The crenels (the gaps in between) gave the fortifications the name ‘crenellation’ with defensive merlons, arrow slits to combat invaders and crenels for keeping watch.

– There is only one small room remaining in the castle, this is the Garderobe. It acted as store room, with the name deriving from the same word as ‘wardrobe’. However the name covers a plethora of uses and is most commonly used to mean toilet. In this case it functioned as both a store room and toilet!

By Madeleine Cambridge, Manager, Totnes Castle. All photographs © Totnes Castle.