Shown on many older maps as Dashwood Walk, in the 17th century this was a passageway leading to the large house and gardens of Sir Frances Dashwood. A Member of the Common Council of the City, his son succeeded to the title of Baron Le Despencer and later served as Chancellor of the Exchequer by which time the name had been changed.

On its southern side the Walk adjoins the churchyard of St. Botolph-without-Bishopsgate, where in 1413 a female hermit subsisted on a pension of 40 shillings a year. Bordering the churchyard at that time was an open drain, described a hundred years or so later – by which time the resulting smell was being blamed on Frenchmen living in the area – as being full of ‘soilage of houses, with other filthiness cast into the ditch…to the danger of impoisoning the whole city.’

St. Botolph’s itself is one of four City churches dedicated to this seventh century patron saint of travellers, and for this reason was positioned hard by one of the City gates. Three of the four survived the Great Fire, but being generally decrepit this particular one was eventually pulled down and replaced in 1725 at a cost of £10,400 by a new one designed by the George Dance the Elder and his father-in-law James Gould.

St. Botolph’s itself is one of four City churches dedicated to this seventh century patron saint of travellers, and for this reason was positioned hard by one of the City gates. Three of the four survived the Great Fire, but being generally decrepit this particular one was eventually pulled down and replaced in 1725 at a cost of £10,400 by a new one designed by the George Dance the Elder and his father-in-law James Gould.

One weekend in 1982 a ghost apparently resident in the church carelessly wandered in front of a camera inadvertently allowing photographer Chris Brackley to take a picture. Unaware of this at the time Brackley subsequently found an image of a woman in old-fashioned clothing standing on the balcony when he developed the picture – even though he knew that no such individual had been in the church at the time.

St. Botolph’s also once oversaw a charity school for fifty poor boys and girls, and although its two decorative painted Coade stone figures of charity children have now been removed from its front of the building the old school room can still be seen in the attractive churchyard to the west of the church.

The poet John Keats was christened here in 1795, as was the actor, benefactor and ‘Master Overseer and Ruler of the Bears, Bulls and Mastiff Dogs’ Edward Alleyn; Sir Paul Pindar, the façade of whose mansion is preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, was a parishioner. The memorial cross in the churchyard is believed to be the first Great War memorial in the country, having been erected in 1916 following the Battle of Jutland and the death of Lord Kitchener.

The poet John Keats was christened here in 1795, as was the actor, benefactor and ‘Master Overseer and Ruler of the Bears, Bulls and Mastiff Dogs’ Edward Alleyn; Sir Paul Pindar, the façade of whose mansion is preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, was a parishioner. The memorial cross in the churchyard is believed to be the first Great War memorial in the country, having been erected in 1916 following the Battle of Jutland and the death of Lord Kitchener.

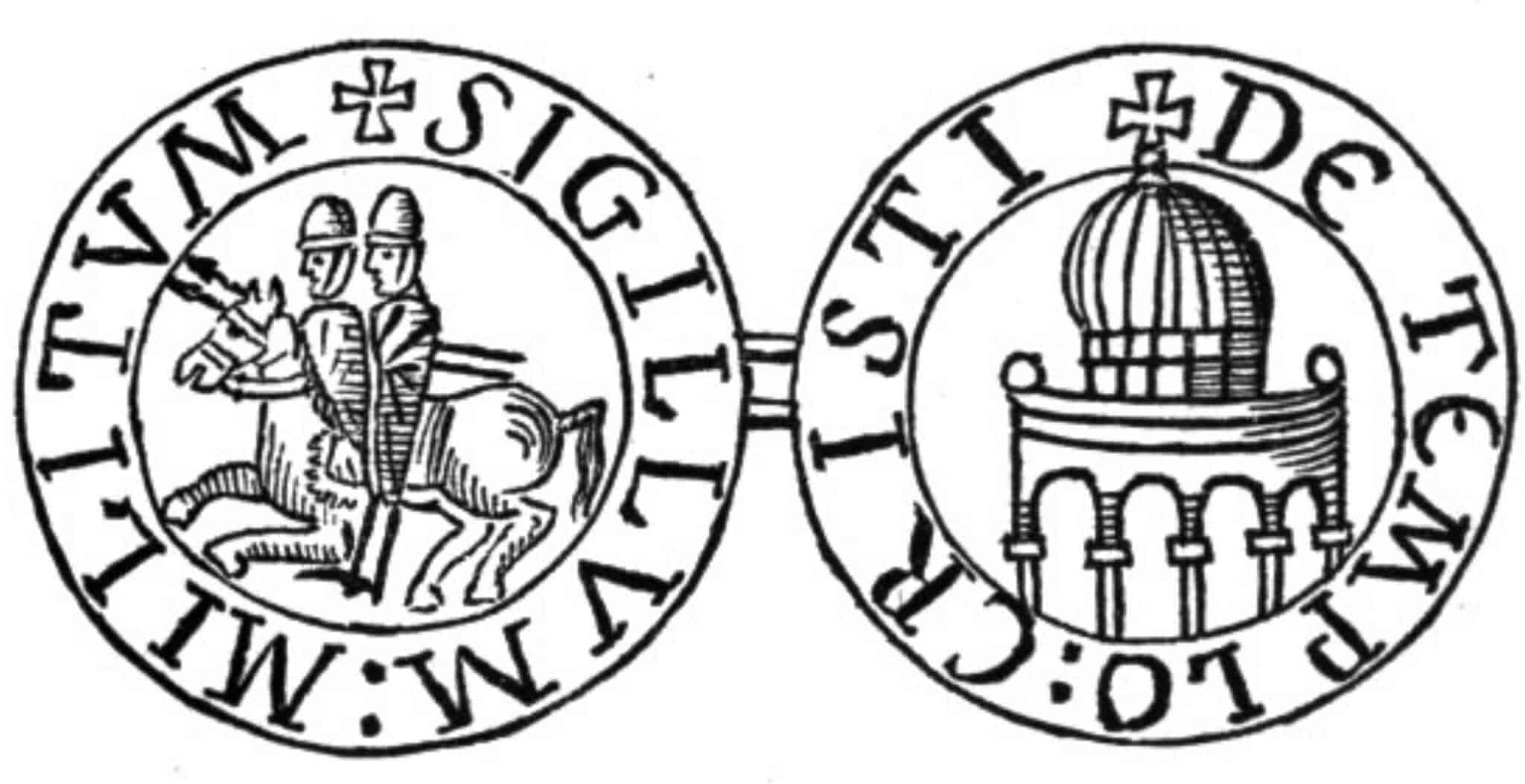

The latter is by no means the most singular feature of the churchyard, however, a claim which belongs to premises of a cocktail bar now known as The Bathhouse. Reputedly modelled on a shrine forming part of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and complete with some lovely Ottoman detailing and even a miniature flattened-onion dome, this charming City curiousity was designed by G. Harold Elphick for the Victorian entrepreneur James Forder and his brother.

The structure originally formed the above-ground entrance for the Forders’ extensive subterranean suite of luxurious Turkish baths, the brothers seeking to cash in on a Victorian craze for such things which saw more than 600 such establishments opening up and down the country.

Few were as exotic, architecturally, as this one however and having somehow survived the Blitz, the inevitable attempts at redevelopment and a steadily declining interest in this particular leisure pursuit, the City’s only Oriental building slowly lost its faïence tiles of tin-glazed earthenware, the cooling fountains of filtered water, the marble mosaic floors, stained-glass windows, and choice of rose, douche, needle or spiral showers. Happily much of the original tilework decoration survives, including several ‘Moorish’ interlocking designs which Elphick himself designed and had specially manufactured by Craven Dunnill at Jackfield in Shropshire’s famous Ironbridge Gorge.

© David Long

for Historic UK Ltd.

Tours of Historic London

Find out more about this great city by browsing our Selected Tours of London.