When you visit our caves here at Beer Quarry you will face a mystery; the same one we do. The caves are very little formally documented.

The academic record of our existence is a tad light, like about 99% of what happened here is missing. But as you walk along our two miles of dark passages and our huge caverns, you can do something quite unique, that no other heritage site in our country can offer. You can reach your hands out and touch walls, place your hands where quarrymen, women sometimes, and children worked those walls during the whole span of English history. Two thousand years of it, we estimate.

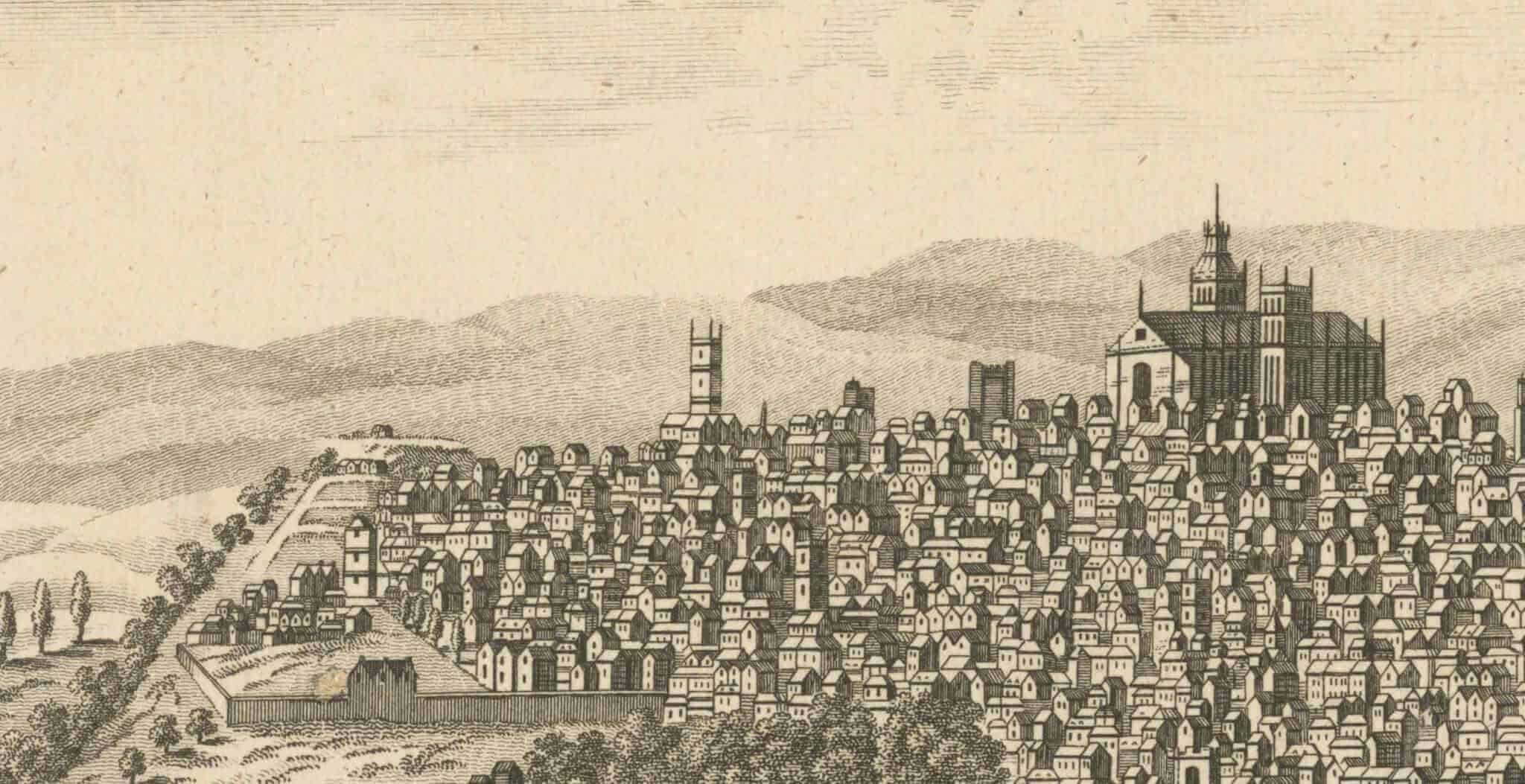

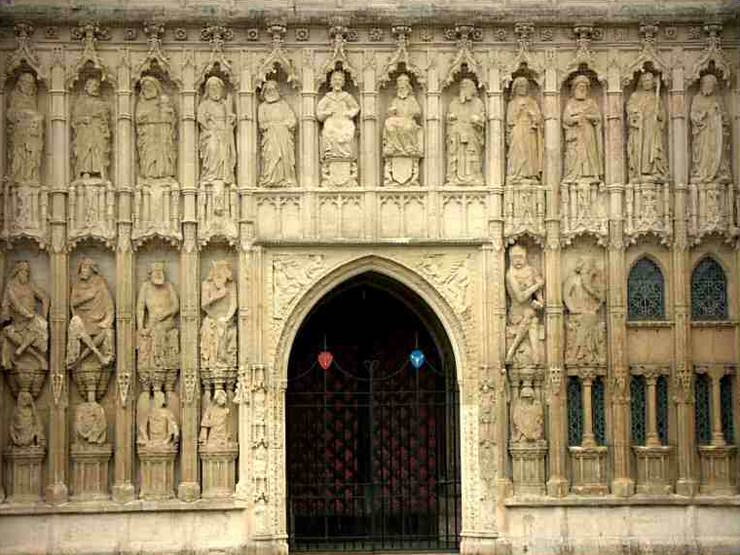

The major periods of English, later British and now UK history, are here for you to see and touch. That’s what’s different at Beer Quarry Caves. This isn’t the site of a battle or a palace. It’s a place where the most ordinary thing in all of human history happened. People worked here. But unlike what you can see when you visit the great palaces and cathedrals, sometimes built with the very stone cut from these caves, here you can see and touch the most ordinary element of human history; work.

Let us walk you briefly through the caves and this extraordinary history.

The Romans opened the limestone seam in what you will see as the entrance, around 47 AD. There are 17 other closed entrances, awaiting exploration. From the Roman entrance you walk left into the Anglo Saxon portion of the caves, followed by the Norman period, and then into the modern period. In the great rear caverns, you can see where munitions were stored during World War Two, when we stood alone against the Nazi hordes across the channel. Those caverns were also used to grow food, including mushrooms for London during the blitz.

So what can we say with any kind of certainty?

We tend to think of the Romans as soldiers, as warriors, fighting their way all over the place. That is sometimes true but predominantly the Romans and their allies were builders. They built villas, temples, roads and theatres. And they spent a lot more time doing that than hacking people to bits with blunt, rusty swords. We know that the Romans had discovered Beer Quarry because Beer Quarry stone was found at the Roman Villa (we think it was a barracks) at Honeyditches in Seaton.

Which is the first step towards the bigger picture. The caves are set in a very interesting local context, of water flows and Stone Age settlements. The stream that flows through Beer village is said not to have dried up since Roman times. The known Stone Age settlements are Blackbury Camp, Sidbury Castle and Farway. The yet to be discovered settlement is Beer itself. But in Roman times Axmouth was a Roman sea port, and the great Roman road from the north, the Fosse Way, terminated there, and not at Honiton as is sometimes thought.

But going back into our caves, into the thing that’s hardest for us to figure; the darkness. The men, women and children who worked here worked in darkness, lit, if they were lucky, by tallow candles that they had to buy themselves, from the leaseholder. Their job was to carve great building blocks out of the seam of limestone laid down about 100 million years ago. The floor you walk on is that old. Its older than we can easily imagine, but it sets the frame for another part of the Beer Quarry context. The caves are dug into a local geological framework that is, quite literally, hundreds of millions of years old.

An ancient aquifer and water that’s millions of years old.

Deep down beneath your feet is the East Devin aquifer. If what we know is correct that aquifer was created between one hundred million and three hundred million years ago. This year we will be testing the water to see if one day we may be able to offer water to drink that is millions of years old. Possibly the oldest on earth?

In the first English Domesday of 1086 a small hamlet is recorded at Beer. In the 2nd English Domesday of 1872 Beer had grown and there is a reference to how the caves were valued for that Domesday.

By the 1920’s large scale quarrying had ceased but we do possess a small residual licence to supply our old customers at places like Exeter Cathedral, with maintenance level Beer stone.

The first payroll record we have is held at Exeter Cathedral and is dated 1279. The Cathedral also records the transition from quarrying techniques that had little changed from Roman times, to increased mechanisation and distribution methods. The cost of axels is recorded in the Cathedral accounts.

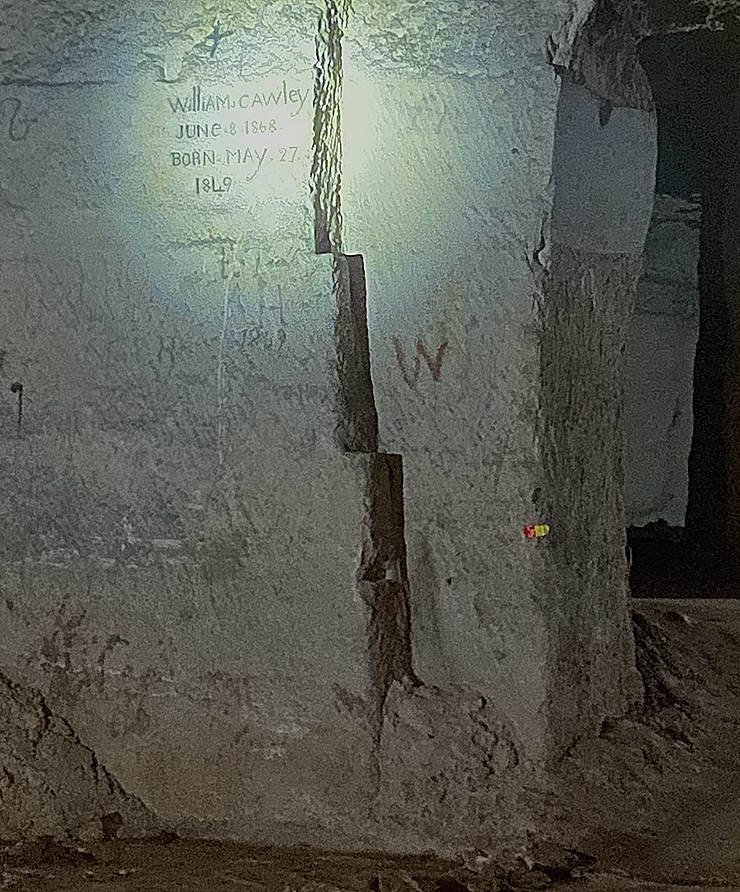

Our guides will tell you much more about our recent history. About the smuggler Jack Rattenbury who is said to have hidden his contraband in the caves and who was given a pension of a shilling a week by the local Lord, Lord Rolle. And about the names written on our walls. One of the incidents they will show you is a collapsed tunnel where up to 47 quarrymen were thought to have died in the 1750’s in an explosion which we are still researching.

They will also tell you of the fate of the excisemen, not all of whom were much loved in Beer. At least one is thought to have drowned in 3 ins of water in Beer Brook, in broad daylight. Another fell off Beer Head, with no witnesses present.

Over recent years and before the pandemic the caves hosted drama and choir recitals, including Shakespeare and Greek tragedies that were older than the caves themselves. We hope to resume our drama events this year.

The chapel in the caves. The Stations of the Cross in Cornish after over 500 years.

Inside our caves is a chapel, a relic of the Reformation, one of the greatest upheavals in British history. This is where local Catholics came to say their prayers and hear Mass when their own religion was banned by the Crown. Until the late 1800 hundreds, there was an altar and a crucifix on the wall of the chapel.

They vanished early in the 20th century and we have not even been able to get a photograph of the artefacts.

But this year, or early next year, we are hoping to premier for Devon, an ancient form of Catholic worship known as the Stations of the Cross. It will be held in Cornish, the lost language of our neighbours to the west. This devotion in this revived form has not been heard in Cornish for, we think, over 550 years. And is staged in a form common to all Christian denominations, nowadays. The music has been composed by Ben Sutcliffe and Zaid Al Abib, and combines the music of the Middle East, the birthplace of Jesus Christ, with more modern and classical material. Those familiar with Islam will know that Jesus Christ is a significant figure in that religion, whose echoes can be heard in Ben and Zaid’s music.

Scallop baguettes and Lyme Bay mackerel and cod. Fresh from the boats for Steve’s Friday specials

When you visit our caves this year we also hope to offer you a very special culinary delight, all fresh from Lyme Bay – where we think our Stone and Bronze Age ancestors got their fish from. Steve, the Cave director, spent last year rehearsing his food offerings and hopes to offer Scallop Baguettes and Lyme Bay mackerel and cod , crab and lobster, fresh from the boats down on Beer beach, with Friday evenings as ‘fish’ evenings. There are few more magical ways to spend a Summer evening in Devon than sitting out at Beer Caves, listening to the birdsong and watching the prolific wildlife. Once upon a time it was traditional to avoid meat on Fridays and we hope to revive that tradition. We now have our own licences and will offer a selection of local ciders, wines and even 100 million year old non alcoholic water, if we can, to accompany the food.

Steve is also the Cave’s ‘Flintmaster’ who is collecting local flint to further establish the use we think both the Romans and the local folk made of that material long ago. Before Beer Quarry Caves were a lime stone mine, we think they were a flint mine.

Finally, there are our bats. We host a mixed tribe of bats, some rare. This year we are hoping to connect to the rapidly growing scientific interest in bats. Bats apparently don’t get cancer, and are immune to all sorts of things we aren’t. And they are the only flying mammals to evolve in Britain.

For more information, please visit Beer Quarry Caves.

By Kevin Cahill, historian in residence, Fellow emeritus of the Royal Historical Society

Published 20th June 2023