Flowing through Bigbury-on-Sea and Bantham in South Devon, the Avon Estuary is a beautiful coastal area boasting popular beaches and a surfer’s paradise. Below the sand lies a fascinating Dark Age history that was forgotten for a thousand years…

Burgh Island from Bantham Beach, showing Bantham’s Sand Dunes in the foreground, offering a view that has captivated visitors for centuries. Photo by Mike Edwardson.

Burgh Island from Bantham Beach, showing Bantham’s Sand Dunes in the foreground, offering a view that has captivated visitors for centuries. Photo by Mike Edwardson.

In a county blessed with rolling countryside and serene sea views, Bantham Sands and Bigbury-on-Sea stand out for their breathtaking scenery. The estuary of the Avon stretches out between them amid roaring waves, looking out onto Burgh, the picturesque tidal island that inspired Agatha Christie. But long before crowds flocked here for leisure, merchants from far-flung lands dropped anchor in these sparkling waters. They traded with Devon’s Dark Age inhabitants, keeping a connection to the Roman world alive at a time when it had all but died in the east of Britain.

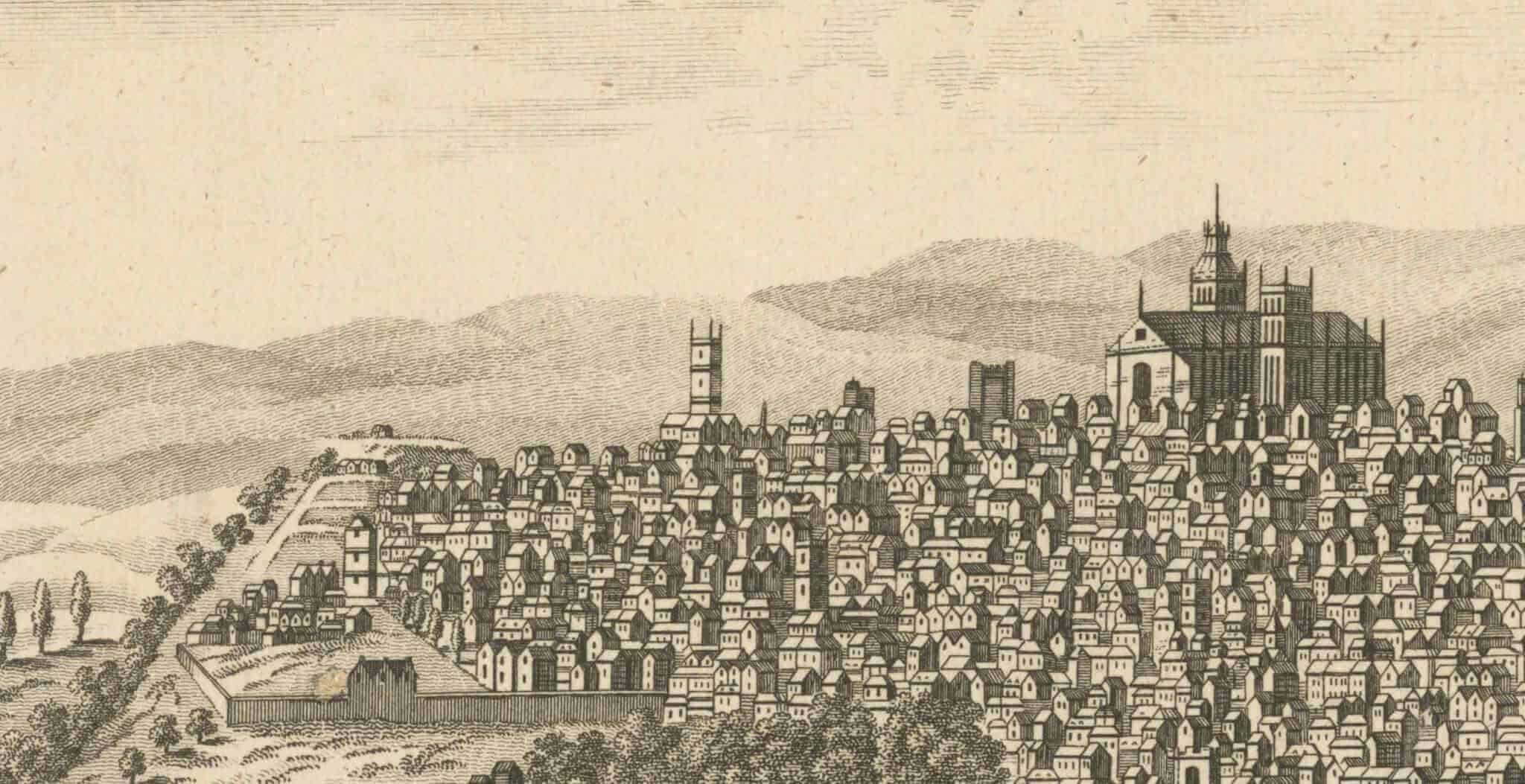

The area’s history as a maritime trading hub may go back to the classical world. Burgh Island is a candidate location for the Isle of ‘Ictis’, mentioned by ancient Greek writer Diodorous Siculus in the 1st Century BCE as an island where the Britons traded their valuable tin with seafaring merchants. Tin ingots found nearby in an ancient wreck may support this idea. But it was some four centuries later, after the Roman Empire left Britain, that these beaches saw an explosion of trade activity. Excavations have found the remains of a large settlement beneath Bantham’s rolling dunes, as well as over 500 pieces of Mediterranean style pottery and North African tableware dating from the late 5th and early 6th centuries CE, when the East Roman Empire was making a resurgence.

This indicates that merchants from the embattled remnants of the Roman world were bringing a taste of the old empire back to Dark Age Devonians. At this time, Devon was part of the Romano-British Kingdom of Dumnonia. One of many British kingdoms that sprang up in the wake of Rome’s retreat, it may have ruled the South-West from Land’s End to Salisbury Plain. The Kingdom’s elites likely hungered after Mediterranean goods, such as fine wines and the exotic vases in which they came, as status symbols that visibly connected them to their Roman predecessors. The same kind of goods were also traded at contemporary sites like Tintagel in Cornwall, and the elites of South Devon would not have wanted to be outcompeted by their Cornish comrades. The sheltered moorings of the Avon estuary offered a perfect area to which local leaders could invite Mediterranean merchants. Perhaps this was enhanced by the striking presence of Burgh Island, whose tidal nature was of a type invested with religious significance throughout the region. It may have lent sanctity to the landscape, enhancing it as a place for diplomacy as well as trade. Meanwhile, the visiting merchants would have gained access to British tin, which was as rare a resource to them as it had once been to Diodorous Siculus.

The evidence suggests that these meetings were not merely business transactions, but grand events. During excavations at Bantham in 2001, Exeter Archaeology uncovered hearths made from beach pebbles and 2,400 fragments of cattle, pig, shellfish, and other food sources. They also found Cornish-produced pottery, never before found alongside imported wares. For the archaeologists, this painted a picture of intensive feasting as well as trade. Perhaps even the Kings of Dumnonia themselves rode to Bantham to greet their visitors, treating this as a chance to conduct international diplomacy. They can be pictured stood on the sands in their finery, ceremonially exchanging gifts with Mediterranean envoys and making pledges of alliance. They may then have cemented this by gorging together on meat and shellfish, quaffing Italian wine around roaring beach-bonfires, while music played and waves crashed to shore behind them. It is possible that, the next morning, the Dumnonians hosted their fellow Christians for a religious ceremony on Burgh Island, to sanctify relations and bless the voyage home.

However, these connections were not to last forever. As the 6th century wore on, the customary trade routes were disrupted by plague, a worsening climate, and political upheaval in the Mediterranean. The merchant’s visits to Bantham dwindled. The trade almost completely died out by the 8th century. Meanwhile, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex advanced inexorably into Dumnonia, likely conquering Devon no later than the turn of the 9th century. After this, any memory of the site’s significance probably disappeared, leaving only ruins to be swept beneath the sands and forgotten.

While the debris lay buried, Bantham and Bigbury became quiet areas of fishing and farming. Burgh Island may have retained its spiritual significance for a period – in medieval times it seems to have been known as ‘St Michael’s Island’, much like St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall and Mont St Michel in Normandy. Those other islands once hosted monasteries, and it is possible that Burgh may also have had a holy house, though firm evidence for this is elusive. There is conjecture that Burgh’s longstanding pub, The Pilchard Inn (which dates its establishment to 1336) began life as guest lodgings for the monastery. A tempting idea – but any proof likely lies buried beneath the island’s modern hotel. Over time, Burgh lost the name ‘St Michael’ (a map from 1765 shows it only as “Borough or Bur Isle”) along with any explicit religious association. But any visitor today need only stand atop Burgh’s summit and look around, taking in the deep blue brilliance of the sea flowing into the green-gold estuary landscape, to sense the island’s soul-nourishing quality.

While Burgh may retain some of its mysteries, Bantham has gradually revealed its own over the years. A great storm, the ‘November Gale’ of 1703, exposed ancient waste dumps and bones (which locals took to use for fertiliser). Thus, uncovered after a millennium, the site gradually became of archaeological interest. Excavations in 1978 and 2001 revealed much that was pieced together to tell the area’s Dark Age story. Bantham is now a scheduled Monument, protected by Historic England. Today, visitors can walk these sands and imagine the vibrant history that unfolded here in distant days, making Bantham and Bigbury-on-Sea not just places of natural beauty, but windows into Britain’s rich past.

Mike Edwardson is a professional analyst and writer with an MA in History from The University of Sheffield. Passionate about uncovering the lesser-known stories of British history, Mike combines his analytical skills with a love for storytelling to bring the past to life.

Published: 14th June 2024