The rugged hills of Bodmin Moor attract visitors year-round with their windswept beauty and timeless allure. Nestled on the Moor’s southeast fringe lies an area rich in historic treasures, from a striking Neolithic tomb to evidence of Cornwall’s last recorded King…

The solitary moors of Bodmin have an ethereal, timeless quality which makes it fitting that they host many fascinating historical sites. In particular, the area around St Cleer Parish, intersecting with the Moor’s South-East corner, packs several enchanting historic monuments into a small area. All are easily accessible, within fifteen minutes drive of each other.

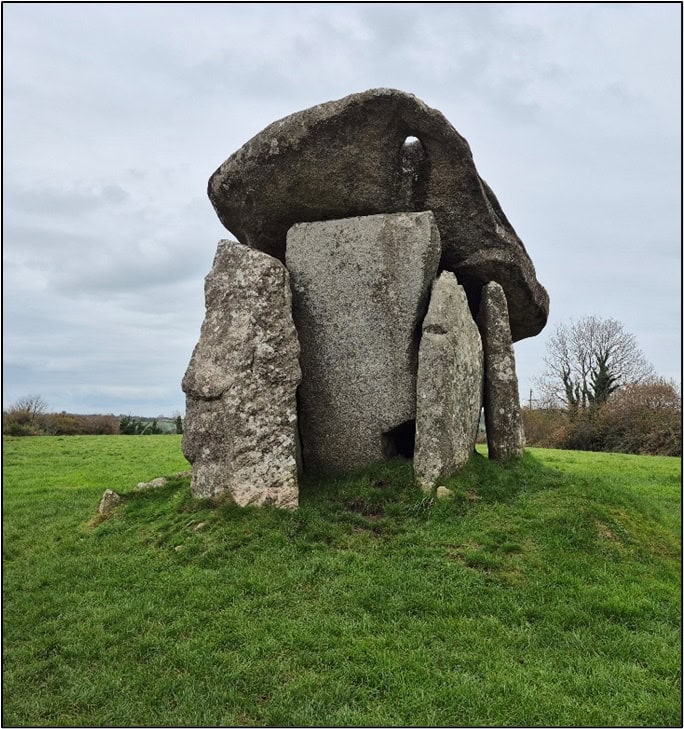

The oldest, standing solitary yet stalwart in a field near the village of Darite, is Trevethy Quoit. It is amazing to think that this structure was likely constructed around 5,500 years ago, between 3700-3300 BCE. Its architects were some of Britain’s first Neolithic-period farmers. They built a tomb of a type commonly called a Dolmen – made with large blocks of stone. Six large granite slabs were fixed in the earth to support a huge, 20-tonne capstone (roof). Originally, it would also have been covered with smaller rock cairns and/or a surrounding mound of earth, with only the front stone left clear, creating an artificial hillock. Within, Cornwall’s early farmers laid their dead to rest, leaving a seemingly intentional gap in the bottom right corner of the front stone – was this an entrance for offerings, and communions with the ancestors?

Trevethy Quoit’s meaning – the significance which it held for those who built it and lived in its shadow – is a subject without firm answers. We may consider that this seems to be an early structure, raised within a few centuries of the first farmers arriving on these shores. The British landscape was very different then – heavily forested, stalked by predators like wolves and bears, and indeed the pre-existing British hunter-gatherers. Before cultivating the land, the farmers needed to clear the forests, and perhaps the forest’s inhabitants, by the blade of the axe. Maybe the tomb honoured those who achieved success, and asserted lasting ownership of the land? Note also that Trevethy Quoit faces east/southeast, towards the rising dawn. Perhaps, having cut away the thick forest to bring sunlight to their precious crops, the ancient farmers wished the sunrise to shine on their ancestors as well, in the hope that they too might be given new life? This may explain the hole visible in the front-right corner of the capstone: was it originally positioned to shine a celestial light on the entrance?

Examples of such Dolmen tombs are found all over Britain – Trevethy Quoit stands out for how well it has survived the ages. While its earthen mound has long eroded away, and its back-stone has fallen in, most of the structure still stands as intended; it has a claim to being the best-preserved tomb in Cornwall, despite probably being older than most. Trevethy Quoit remains today as a proud monument, giving silent testimony to the dead whom it has guarded for more than 5,000 years.

Perhaps this mighty tomb lent the area an enduring importance, for around 1,000 years later, in the late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age, a new kind of monument was erected nearby. A few miles to the north, near the village of Minions, stand three back-to-back stone circles, known as ‘The Hurlers’ for their resemblance to players of the traditional Cornish game. They lie on a southwest to northeast axis, with the middle circle being elliptical while the outer circles are more perfectly circular. Two other monoliths, ‘The Pipers’, stand 100m southwest, possibly intended as gateposts to the site.

Such stone circles represent a cultural shift from tomb-building to more abstract structures which took place from the mid-Neolithic (c. 3,000 BCE) onwards. Was this an evolution, rather than a break in the culture? Either way, these stones were erected on a prominent hillside likely cleared of forest, which offered panoramic views south to the sea, east to Dartmoor and west towards Bodmin. Further, the formidable outcrop of Stowe’s Hill, topped by the curious rock formation known as the ‘cheese-ring’, lies just ten minutes’ walk to the north, and the immediate area is rich in tombs (including Trevethy). This has led some to speculate that the circles marked a ceremonial point on a religious processional route. Possibly they also served as a place for communal gatherings, with locals summoned perhaps by a beacon lit on the summit of Stowe’s hill. Clearly, centuries after Trevethy Quoit was raised, this area retained great spiritual significance.

Even in later Millennia, the landscape’s ceremonial value persisted, as evidenced by King Doniert’s Stone. Built some two and a half thousand years later, around 875 CE, the stone stands just over two miles from ‘The Hurlers’, broken and stooped, appearing easily overlooked. However, this was once the pillar of a large Celtic style cross which would have been visible for miles around. And like the Pillar of Elliseg, its contemporary counterpart in North Wales, it likely memorialized a King. On one side, dulled by time, is a Latin inscription, translated as: ‘Doniert asks prayers for his soul’. Doniert has long been identified with the last recorded King of Cornwall, named as ‘Dumgarth’ in the 12th century Welsh Annals, and stated as having drowned in the year 875. Next to it stands another stone base for a cross, known as the ‘other half stone’. Their intended relationship with each other is unclear.

This monument is of a much later date than its prehistoric neighbours, but mystery surrounds it too. In the late 9th century, Cornwall is assessed to have been a vassal of the Kingdom of Wessex, retaining its Celtic culture, language and a degree of political freedom from Wessex, its Anglo-Saxon overlord. But details are scant. Was Doniert truly the last Cornish King, or just the last whose name has survived? And was his cross erected here, so close to Trevethy Quoit and ‘The Hurlers’, because a folk memory lingered of the area’s ancient spiritual importance?

It is a tempting idea, but any confirmatory evidence is unlikely to be forthcoming. Still, today, visitors can explore these historic sites within a few hours. They can walk the sweeping moors, stand in the shadows of ancient stones, and marvel at the monumental power invested over thousands of years in this dramatic corner of Cornwall.

Mike Edwardson is a professional analyst and writer with an MA in History from The University of Sheffield. Passionate about uncovering the lesser-known stories of British history, Mike combines his analytical skills with a love for storytelling to bring the past to life.

Published: 20th January 2025.