From around 200 AD, the shape of London was defined by one single structure; it’s massive city wall. From Tower Hill in the East to Blackfriars Station in the West, the wall stretched for two miles around the ancient City of London.

With only a few exceptions, the line of the wall remained unchanged for 1700 years. Its original construction was thought to be as a protective measure against the Picts, although some historians argue that it was built by Albinus, governor of Britain, to protect his city against his arch rival Septimius Severus.

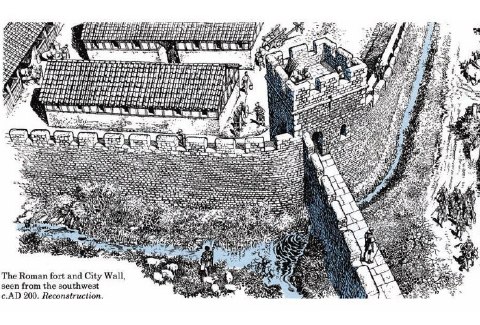

Whatever the reasons for its inception, the wall stood as one of the largest construction projects carried out in Roman Britain. It was also rebuilt and extended numerous times throughout the Roman period, requiring somewhere in the region of 85,000 tons of Kentish ragstone to complete. The wall included over 20 bastions, mainly concentrated around the Eastern section, as well as a large 12 acre fort on the north-west section of the wall.

The fort itself was the home of the official guard of the Governor of Britain, and would have housed around 1,000 men in a series of barrack blocks. The fort would also have included a series of administrative buildings, stores and other self contained amenities.

This section of Historic UK’s Secret London series will take you on a journey around the surviving fragments of this once great wall. Starting at Tower Hill, we will travel north to Aldgate and Bishopsgate. We will then turn West and head along the north side of the wall, past Moorgate, Cripplegate and West Cripplegate. At this point we will explore the remains of the old Roman Fort, before heading South towards Newgate, Ludgate and Blackfriars

Tower Hill Postern Gate

Our journey begins at the extreme South East side of the old city wall, directly adjacent to the Tower of London. The remains are actually of a medieval gatehouse which would have been built into the side of the Tower of London’s moat. Although there is limited archaeological evidence to show that the gatehouse was built on the site of a much older Roman gate, most historians are agreed that this was probably the case.

What we do know is that the medieval gatehouse had a most troubled history. Built with sub-standard foundations, and due to its proximity to the Tower’s moat, the gate was not of sound construction and subsequently started to crumble and partially collapse in 1440. Perhaps the best description of this event is by John Stow in his A Survey of London – 1603:

"But the Southside of this gate being then by undermining at the foundation loosed, and greately weakned, at length, to wit, after 200. yeares and odde the same fell downe in the yeare 1440."

Stow goes on to write a rather damming indictment of those who rebuilt the gatehouse…:

"Such was their negligence then, and hath bred some trouble to their successors, since they suffered a weake and wooden building to be there made, inhabited by persons of lewde life…"

It was no doubt due to these “lewde life” squatters that by the 18th century the gatehouse had crumbled and disappeared into the ground. It was to remain hidden until excavations in 1979.

Tower Hill Roman Wall

Located in the garden to the east of the Tower Hill underpass (heading towards the DLR station) stands one of the highest remaining fragments of the old city wall. What is interesting about this section of the wall is that the Roman sections are clearly visible towards the base of the wall, up to about 4 metres high. The rest of the stonework is of medieval origins, and stands today at a height of around 10 metres.

In its heyday this section of the Roman Wall would have stood at around 6 metres high, with this eastern section including a high density of bastions. On the other side of the wall would have been a deep ditch providing additional defensive measures. This ditch would have both enhanced the height of the wall from the exterior, whilst also turning the ground into a water laden bog.

During the medieval period this area was the site of Tower Hill scaffold, where dangerous criminals, pirates and political dissidents were publicly beheaded. Among the people beheaded just to the West of the old Roman wall were Sir Thomas More, Guilford Dudley (the husband of Lady Jane Grey) and Lord Lovat (the last man to be executed in this way in England).

Cooper’s Row Wall

Much like the Tower Hill section of the city wall, the Roman fragments can still be seen up to about 4 metres high. Again, the rest of the wall is medieval in origin, even the archer's loopholes are still in evidence. The Museum of London writes that because there appears to be no stone structure to allow archers access to the loopholes, there was likely a timber platform that allowed movement between them. The museum also states that this section of the wall is unique in its defenses, suggesting that special care was taken with these defences due to their proximity to the Tower.

‘Blink and you’ll miss it’ pretty much sums up how to find this section of the wall. Simply head up Cooper’s Row from the Tower of London and keep an eye out on your right hand side. As soon you find The Grange City Hotel head towards the courtyard and you’ll find the wall.

Vine Street Roman Wall

On the west side of Vine Street, where the road opens out slightly into an extremely small square, is the fourth stop on our Roman Wall tour. This 10 metre length of the Roman City Wall also includes the base of a bastion tower. These towers were scattered along the eastern branch of the wall and were mostly built in the 4th century. During its heyday the tower would have reached somewhere between 9 – 10 metres high, and would have housed catapults firing iron-tipped arrows.

It is thought that this tower was demolished during the 13th century, although other towers in the area were used throughout the medieval period.

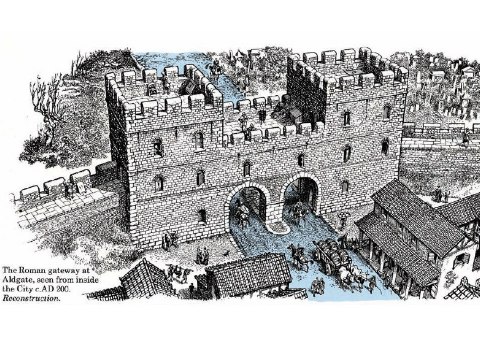

Aldgate Roman Wall

Aldgate was once the oldest gatehouse into London, build decades before the Roman Wall that subsequently adjoined it. It was also one of the busiest gatehouses on the wall, as it stood upon the main Roman road linking London to Colchester. During its 1600 year history the gate was rebuilt three times and finally pulled down in 1761 to improve traffic access.

Aldgate was also once the home of the famous poet Geoffrey Chaucer, who lived in the rooms over the gate from 1374. At the time he was working as a customs official at one of the local ports!

Unfortunately for visitors, there’s absolutely nothing left of the original Aldgate. Instead, look out for a plaque on the wall of Sir John Cass School.

Dukes Place Wall

Before we get into the history of the Roman Wall at Dukes Place, it’s worth pointing out that it’s actually located in a subway! This section of the wall was found during excavations in 1977 during the construction of the underpass, and a cross section of the wall (including the Roman and medieval stonework) can still be seen in the subway walls.

The bottom of the Roman wall is actually around 4 metres below street level. The reason for this is that over the centuries the land level has risen in London due to additional buildings, soil and rubbish being piled on top of each other. It is even reported that by the medieval period the ground level had already risen by 2 metres.

During the medieval period, this area was home to an Augustinian Priory. Originally founded in 1108 by Queen Matilda, the priory owned a great deal of the land and properties surrounding Aldgate.

Bishopsgate

Perhaps the most famous street in the City of London, Bishopsgate derives its name from the Roman gate that once stood at the junction of Wormwood Street. Much like Aldgate, Bishopsgate was one of the busier junctions into and out of the City of London due to it’s positioning on a major road, in this instance Ermine Street which ran to York.

The original Bishopsgate stood until the Middle Ages when it was rebuilt, and during this time it because renowned for having the heads of recently executed criminals displayed on spikes above the gate.

Unfortunately nothing exists of the original gate, and no excavation work has ever taken place on the site. Nevertheless, if you find your way to the newly built Heron Tower and look to the east above Boots chemist, you’ll see a Bishop’s Mitre built high into the stonework. This marks the spot of the original gate.

All Hallows on the Wall

At this point of our journey, the street called “London Wall” loosely follows the north edge of the old Roman wall. The street once ran alongside the defensive ditch on the outside of the wall, but the alignment was changed slightly during the street widening of 1957 to 1976.

Walking up from Bishopsgate, the first sign of the old city wall is at All Hallows Church. This wonderfully simple building was designed and constructed in 1767 by the renowned architect George Dance the Younger, although the church it replaced dated back to the early 12th century.

One of the wonderful peculiarities with this church is that its vestry is actually built into the foundations of an old Roman wall bastion. Although these foundations are now around 4 meters under ground, the semi-circular shape of the bastion can still be seen in the vestry.

If you head to the front of the church you will also notice a fairly substantial wall. Although the majority of the structure dates from the 18th century, there are still parts of the old medieval city wall built into the section nearest to the church entrance.

St Alphege City Wall

This section of wall was originally built in AD 120 as part of a Roman Fort, although later became incorporated into the much wider city wall. After the building of the city wall, the fort was essentially to become an oversized bastion at the North West tip of the City of London, and was home of the official guard of the Govenor of Britain. To give an idea of its size, in its heyday the fort would have housed around 1,000 men throughout a series of barracks.

This section of wall was to remain an integral part of London’s fortifications until the Saxon period, where after a period of prolonged decline an 11th century church was built in to its foundations. When the church was finally demolished in the 16th century the remains of the wall were left, and were subsequently incorporated into a new stock of buildings. During the following few centuries, cellars were built into the newer houses and subsequently into the wall itself. By the time the Roman portions of the wall were rediscovered after a World War II bombing raid, the cellar work had left a core of only half a metre thick at one end!

Today, the remains of this section of wall are still quite substantial. Although the majority of the Roman stonework has long since disappeared, the bottom half of the wall is mainly medieval in origin. The upper section of the wall dates from the War of the Roses (1477) and is substantially more ornate in character, featuring some decorative stonework.

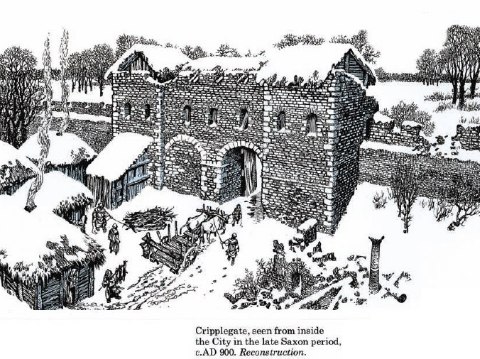

Cripplegate

Once forming the northern entrance to the Roman fort, today the only remnants of Cripplegate is a small plaque honouring its long and eclectic history. Much like the section of nearby wall in St Alphege Gardens, the original Cripplegate was built around AD 120 and began to decline in the Saxon period. However, during the Medieval period the area had somewhat of a resurgence with a large suburban settlement springing up on the northern side of the gate. This new settlement, along with easy access to the nearby village of Islington, meant that the gate was rebuilt in the 1490’s and had somewhat of a renaissance. During the following centuries it was leased as accommodation before being converted into a prison gatehouse!

Along with the majority of the other gates that once lined the ancient city wall, it was finally demolished in the 18th century to improve traffic access.

St Giles Cripplegate Wall

This wonderfully intact section of wall would have been at the north-western tip of the old Roman fort, although most of the surviving stonework is from the medieval period. During this time a series of towers were added to the structure, a couple of which can still be seen in this portion of wall.

A rather unique feature of this portion of wall is the lake that surrounds it; it actually follows the route of a much older medieval defensive ditch. This ditch was eventually filled in during the 17th century and the newly reclaimed land became an extension of the churchyard. This section of the wall subsequently became the southern boundary of the churchyard, and thus escaped relatively unharmed from any redevelopment over the next 200 years.

Moving down the line of the wall, towards the modern bridge spanning the lake, stands a large medieval tower. This tower marks the north-western corner of both the city wall the older Roman fort, and today stands at a remarkable two thirds of its original height. Originally built as a defensive measure, the tower later became a refuge for hermits (no doubt due to its close proximity to St Giles Church). During various redevelopments of the churchyard in the 19th century, the wall became buried in earth and lay hidden until World War II. Due to the heavy bombing in the Cripplegate area, the tower was once again exposed and this process was continued during the construction of the Barbican estate.

Barber-Surgeons' Hall Tower

After reaching St Giles Cripplegate Tower, make a sharp left and continue through the gardens. Once you’ve passed the shrubbery on your left, the gardens will open out and the remains of the Barber-Surgeons’ Hall Tower can be seen.

The history of this part of the wall is quite remarkable. Originally installed as a defensive tower in the 13th century, it was not until the 16th century that buildings started encroaching onto its perimeter. This expansion reached its zenith in 1607 when the Barber-Surgeons’ company built a new hall into the edge of the wall, incorporating the old 13th century tower as an apse.

Unfortunately both the hall and the tower were badly damaged in the Great Fire in 1666, although both were rebuilt in 1678. The structures were rebuilt and restored again in 1752 and 1863. However, in 1940 they were almost completely destroyed by WW2 bombing.

Today the remains of the tower, with its patchwork of stone and brickwork dating from between the 13th and 19th centuries, reflect its turbulent history. Interestingly, if you look at the new Barber-Surgeons’ Hall (opened in 1969) you will notice that an oriel has been incorporated into its design, perhaps as a testament to this little old tower!

Museum of London Tower

Continuing through the gardens you’ll notice the much larger remains of another tower. Originally built in the mid-13th century, this tower was part of a substantial renovation designed to reinforce the defences of the old Roman Wall. John Stow notes this event in his “A Survey of London” published in 1598:

"In the yeare 1257. Henrie the third caused the walles of this Citie, which was sore decaied and destitute of towers, to be repaired in more seemely wise then before, at the common charges of the Citie."

Although originally built as a defensive tower, it was not long until the rapidly expanding City of London began to encroach. By the late medieval period the tower had been repurposed as a house, with arrow slits becoming windows and arches becoming doors (see the plan below, courtesy of the Museum of London).

By the 18th century the old city limits of London had been overrun, and buildings were being constructed against both sides of the old tower, essentially shielding it from view. It remained this way for almost 200 years, until bombing in 1940 revealed the tower once again.

Noble Street Wall

Just across from the Museum of London lies Noble Street, providing a raised platform from which to overlook this long stretch of city wall remains. With stonework dating from the 2nd to 19th century, this section was once again uncovered in 1940 after German bombing of the area. In fact, according to City of London records this area is one of the only remaining examples of a Second World War bomb site in the city!

Originally standing at a height of over 15 feet, the original Roman wall is still evident at the base of the remains. Access to the top of the wall would have been via a set of sentry towers, one of which can still be seen towards the south side of the remains. This sentry tower also marked the south west corner of the old Roman fort.

Moving forward a thousand years, medieval tiling and stonework can be observed at the northern end of the remains. In places where the medieval wall hasn’t survived, a patchwork of 19th century brickwork can be seen.

Historic UK would like to thank The Museum of London for use of the reconstruction images.