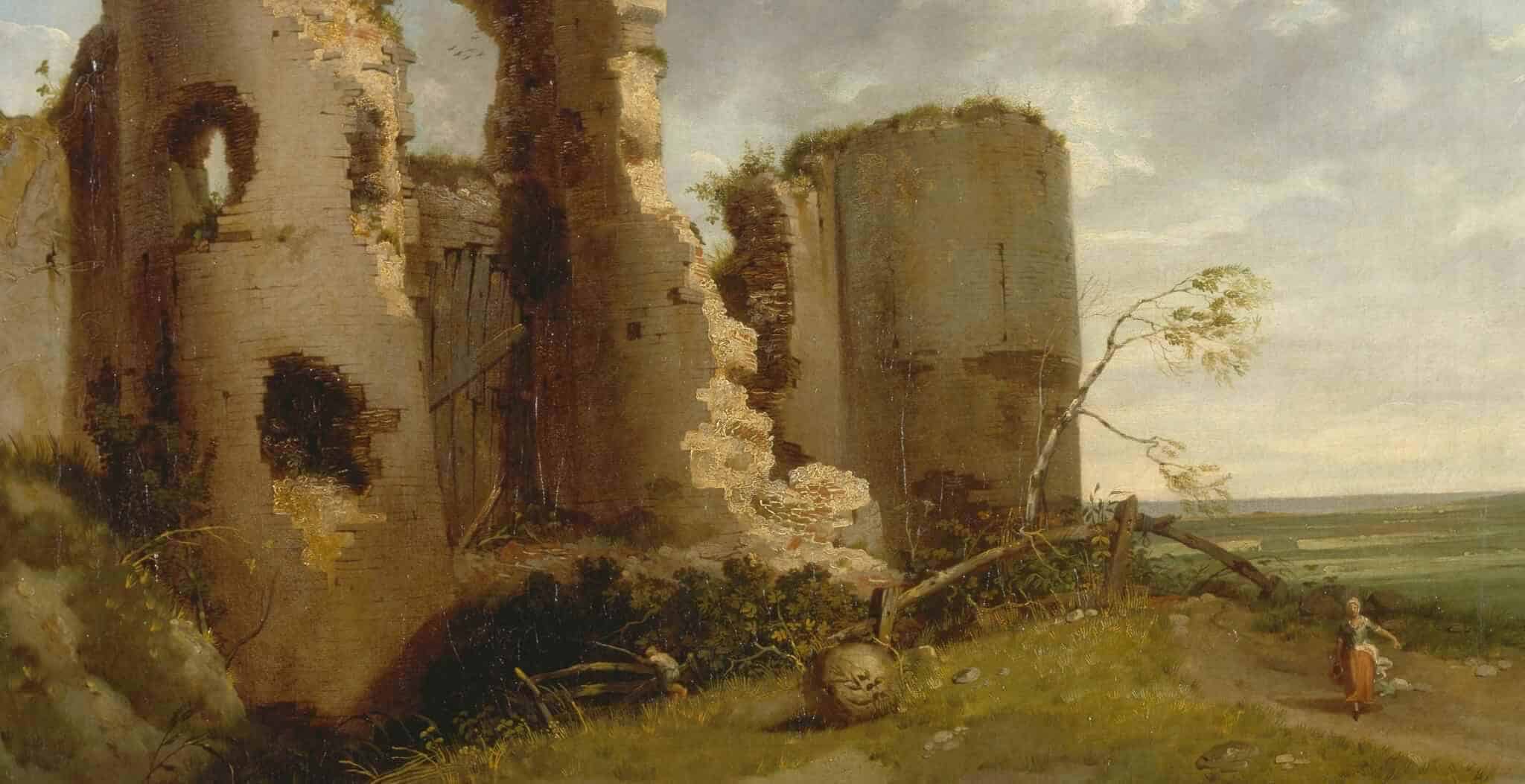

Ruined, battered by storms and catapult balls, and nestling deep in the Sussex countryside near the sea, you can be forgiven for imagining that time long ago forgot Pevensey Castle.

Its crumbling towers, its bare walls made of flint and clay and the austere grassland that surrounds it may mean it doesn’t quite epitomise what we have come to expect from our romantic, Disneyfied medieval castles. But put appearances aside, cross over the drawbridge and enter in between its walls, and a story spanning almost two millennia, richer and more dramatic than you ever imagined, awaits your discovery inside.

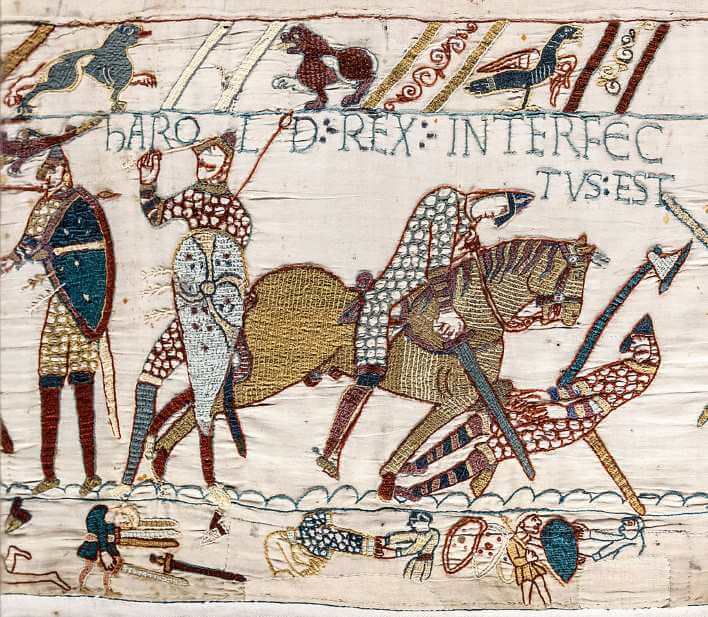

Move forward to the autumn of 1066, and an army of Norsemen, no doubt a little weary and seasick after their voyage across the sea from France, brought a military presence to the old Roman fort once again. William the Bastard, the ambitious Duke of Normandy, decided to halt his forces at Pevensey temporarily as he planned his next move on his quest for the throne of England. Only a matter of days later, William’s army was victorious at Senlac Ridge (now the town of Battle), defeating the Saxon king Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings and taking the crown to become William the Conqueror. Despite the danger and uncertainty of the times, Anderida must have made an impression on the new monarch, for he returned to it shortly afterwards and laid the castle’s first foundations.

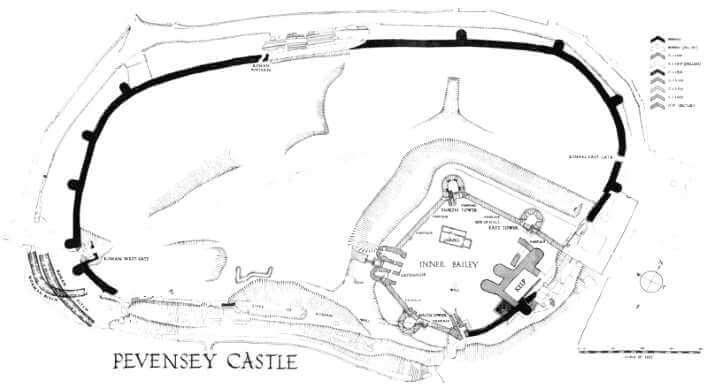

Pevensey Castle was besieged four times during the Middle Ages and it went through the wars (literally) on a number of other occasions. From William Rufus, William the Conqueror’s son and successor, who fought to stop his brother Robert, Duke of Normandy, from usurping the throne in 1088, to the fleet of “Bad King Stephen”, which blockaded the nearby port to starve the Earl of Pembroke and the castle’s other inhabitants into submission. Or from angry Prince Louis of France, who in 1216 launched a raid intent on grabbing a bit of valuable English soil for himself, to the motley, militant mob which – so history relates – set the castle ablaze in 1381 as part of the infamous “Peasants’ Revolt”, a succession of aggressors have sought to destroy the castle (and the people in it) through the ages.

The relics of those desperate times still tell their stories to willing listeners today, like profound scars on an aged body. There’s the oubliette (a hole in the ground with bars across the top), the dingy depths of which bespeak the misery, uncertainty and starvation of those it held captive. There’s the catapult balls, substantial lichen-consumed stone spheres arranged in pyramid piles which in centuries-past were launched through the air and crushed stone and lives alike in violent explosions of debris, screams and blood. And then there’s the moat, now a dry, grass-covered dyke encircling the castle. A nearby gun emplacement is a lasting monument to the time when, in the late seventeenth century, England faced the seaward threat of subjugation by Spain’s aggressively Catholic regime. It’s not the only remnant of those times: in the inner bailey, mounted impressively on a carriage painted stark scarlet and black, the Pevensey Cannon, which guarded Pevensey from 1587 onwards, still survives.

Just a short distance away, through the stone archway that used to serve as the postern gate, Pevensey Harbour was once busy with light craft and barrels full of multitudinous produce being shipped on to the land.

Nearby, rising above the other ruins, the keep – an imposing stone edifice on the eastern side of the inner bailey – was the epicentre of the castle and the ultimate prize for its many besiegers. Local literary great Rudyard Kipling immortalised the medieval drama that may have played out within it in his famous novel, ‘Puck of Pook’s Hill’. Today, the harsh slit of a Second World War gun emplacement cuts the outer stonework like a knight’s helmet. It was here in the 1940s that khaki-clad soldiers looked out from behind their weapons on to a grey sea and a coast strewn with barbed wire. A number of the castle’s old empty spaces were lined with bricks and new floorboards as the British, Canadian and (later) American men stationed to the castle lived in the constant knowledge that a Nazi invasion could come at any moment. If it did, Pevensey would be in the first line of defence. Fortunately, a major amphibious assault never materialised, but the construction of a blockhouse at the entrance of the west gate, the anti-tank cubes and the imposition of concrete at various points underscore to this day the undeniable reality that during modern British history’s most dangerous hour, Pevensey Castle once again resumed its role of guardian of the vulnerable English coast.

Perhaps you leave Pevensey as the sun sets in a blood-red conflagration, a memorial to the violence of long-gone eras. Maybe you make your way along a winding road or bramble-clad footpath leading away from the ruins. You feel like you have come close to touching history: you might have caught the smell of woodsmoke on the gentle breeze, heard the distant trudge of horsehooves, the clink of tools, or the murmur of men’s voices. But it escapes you by a fraction. All you’re left with is the memory of the stone, the open grass and tales of human strife, struggle and fleeting joy filled in by your imagination.

Toby Farmiloe may physically live in London, but his heart and spirit reside firmly in the countryside and often in a past century. Born and bred in East Sussex not far from Pevensey Castle, he has always loved history.