It is the Chinese rather than the British that can claim to be the early pioneers of canal building, with the Grand Canal of China in the tenth century. Even the familiar pound lock still used in Britain today is said to have been invented by Chhiao Wei-Yo, in the year 983. In most instances however, these early canals were merely extensions to natural rivers.

Almost a millennium earlier however, Roman engineers in Britain had built the Fossdyke connecting Lincoln to the River Trent around AD 50, for both drainage and navigation purposes. They also constructed the nearby Caer (or Car) Dyke, extending for almost 40 miles to the south of Lincolnshire, it is believed to have provided a supply route for transporting heavy goods and supplies between Cambridge and York.

In relatively modern times the Exeter Canal in Devon was built in 1566: this bypassed part of the river making navigation easier. The canal was fitted with the first pond locks in Britain, with the now familiar lifting vertical gates.

Other early British canals include a section of the River Welland in Lincolnshire, built in 1670; the Stroudwater Navigation, Gloucestershire, completed in 1779; and the Sankey Canal in Lancashire, which opened in stages between 1757 – 1773.

It was however during the second half of the eighteenth century that the great age of canal building started with the construction of the Bridgewater Canal. This was a time when Britain was bursting with trade, industry and commerce.

Manufacturing had already begun to change, from local craftsmen working in cottage industries to the mills and factories where goods could be mass produced by machines. The factory system imposed a discipline on the workforce which had not previously existed. Set hours and shift patterns established an environment where the workforce could be more easily supervised.

Good communications became vital in order to move raw materials to the factories, and from those same factories, the finished products to the consumer. And not just to consumers in Britain, but throughout the expanding British Empire. Roads were also being constructed and improved, but they couldn’t easily handle heavy and bulky materials like coal and steel, or delicate and fragile materials like pottery. Roads also could not compete with water, where one horse could pull fifty tons of cargo in a boat.

Good communications became vital in order to move raw materials to the factories, and from those same factories, the finished products to the consumer. And not just to consumers in Britain, but throughout the expanding British Empire. Roads were also being constructed and improved, but they couldn’t easily handle heavy and bulky materials like coal and steel, or delicate and fragile materials like pottery. Roads also could not compete with water, where one horse could pull fifty tons of cargo in a boat.

At this time there were over a thousand miles of navigable rivers in Britain, but the problem was, they didn’t go to the right places anymore …the industrial north and the Midlands were not connected with the consumer-based south, nor the ports through which their goods could be exported.

Enter the wealthy young Francis Egerton, the third Duke of Bridgewater, fresh from his Grand Tour of Europe where he had visited the 150 mile long French navigation, the Canal du Midi, completed some years earlier in 1681. It was in 1759 that the Duke decided to build a short canal to link his coal mines at Worsley with the River Irwell, which led directly into Manchester, a big industrial city with an increasing appetite for coal to warm the hearths of the workers.

The Duke outlined the plans with one of his estate managers, John Gilbert, and together they brought in an engineer James Brindley who had already established a reputation working with water power, to manage the detail of the construction. Completed in 1776, the Bridgewater Canal was the catalyst that started half a century of canal building.

The Bridgewater Canal was never linked to the River Irwell as originally planned, but by-passed it, taking the coal from the tunnels driven deep into the Duke’s mines at Worsley, directly into Manchester. With this one astute move they avoided paying tolls to the Irwell Navigation, coal prices in Manchester were halved almost overnight, the Duke became even richer and the furnaces of the Industrial Revolution burned ever brighter.

Brindley was now in great demand and moved on to build even longer navigations spanning the length and the breadth of the country, establishing himself as the leading canal engineer of his, and perhaps of all, time. He is largely associated with the building of the so-called “Grand Cross”, two thousand miles of canals which linked the four great rivers of England, the Severn, the Mersey, the Humber, and the Thames.

There were two concentrated periods of canal building, from 1759 to the early 1770’s and from 1789 to almost the end of the eighteenth century.

In the first period, canals were built to serve the heavy industry of the north and midlands. Meanwhile other regions of England like the mill towns and cities of Lancashire and Yorkshire, the Staffordshire Potteries and the Black Country in the West Midlands were developed and became wealthy as a result of their canal systems.

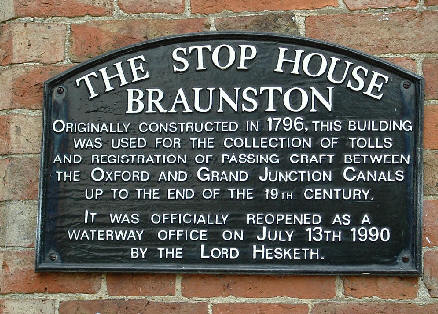

It was not until 1793 that an Act was passed to authorise the construction of the Grand Junction Canal from Braunston on the Oxford Canal to Brentford on the River Thames, just west of London. London itself was not connected directly to the national canal network until 1801.

Funding for these massive infrastructure projects were mainly raised through private venture capital, with most share options being heavily over-subscribed. Promotional meetings were often held in secret, in order to keep the profits in the right pockets. Many canals made significant profits, but some never made a penny for shareholders, and others like the Dorset and Somerset Canal were simply abandoned during construction.

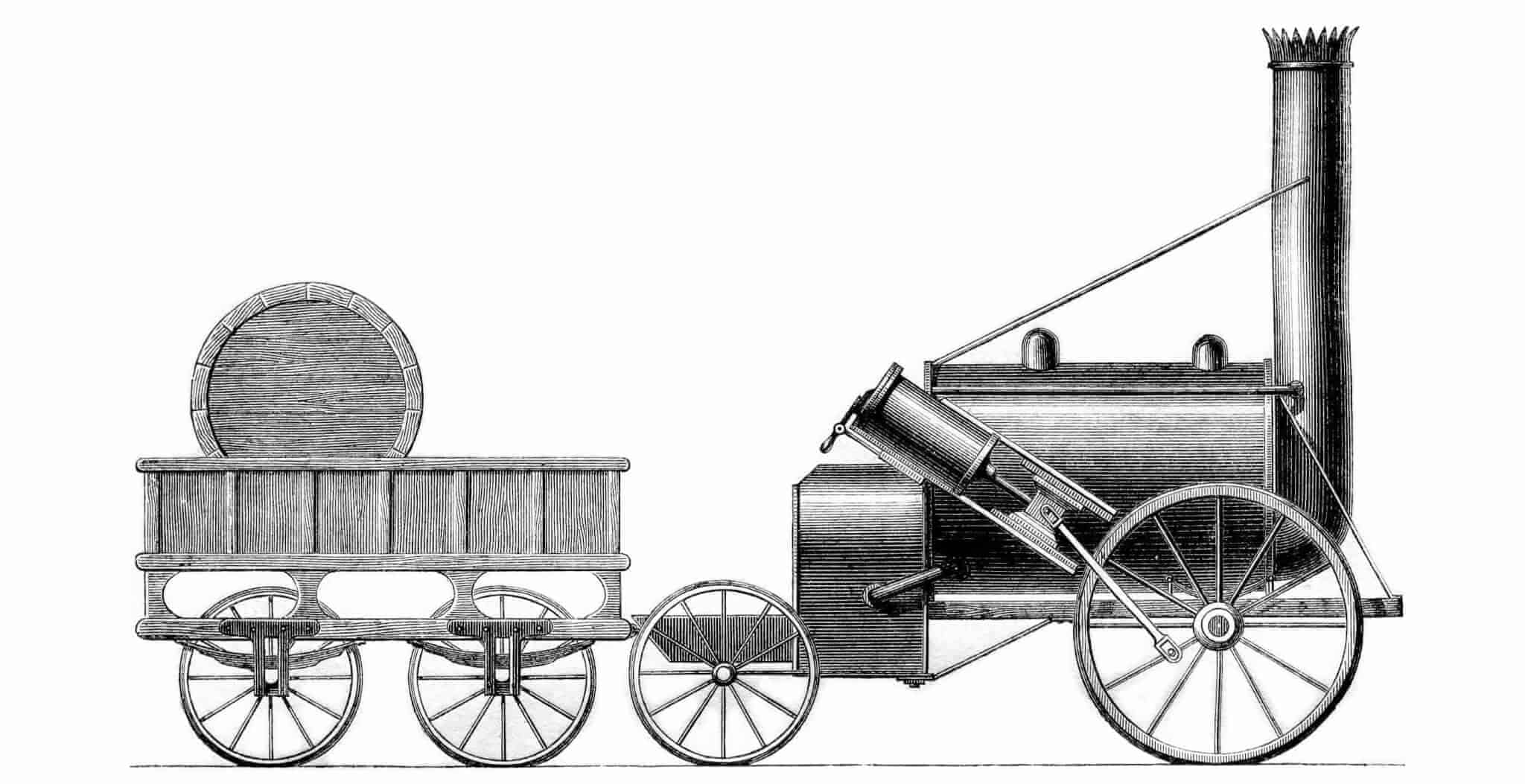

By the end of the eighteenth century the boom was over, and most British canals were completed by 1815. Within ten years the smart money had moved into those new fangled railway schemes.

At first the canals and railways coexisted, the railways concentrating on transporting passengers and light goods and the canals on moving the bulky and heavy goods. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, the railways had been formed into an integrated national network. Such stern competition forced canal tolls down, sending the companies into a decline from which they would never emerge.

After years of neglect and the damage caused by the World War II, Britain’s canal and railway systems were nationalised by the government in 1947. The 1950’s and 1960’s saw a resurgence in the use of canals mainly for leisure purposes, and the Inland Waterways Association was formed to promote their rescue.

Today most commercial traffic is restricted to just a few navigations, the rest of the system is awash with private pleasure boats, hire cruisers, hotel boats and day trip boats.

There are now reckoned to be more boats using the canals of Britain today than ever during its commercial heyday.