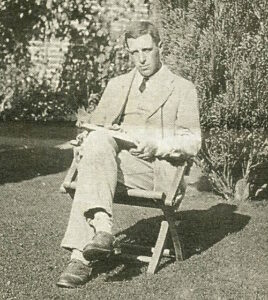

In 1910 Captain Lawrence Oates left his grand Georgian home, Gestingthorpe Hall, near Halstead in Essex to set sail with Captain Scott on his ill-fated bid to be first to the South Pole. Less than two years later Oates uttered his famous last words: ‘I am just going outside and may be some time’. With that he stepped into an Antarctic blizzard. He sacrificed himself in a doomed attempt to save Scott and two other companions, believing he was slowing them down as they desperately tried to reach safety.

Oates, who died on his thirty-second birthday, could have easily never made it to Antarctica at all. Exactly 11 years earlier, in March 1901, he was hit by a sniper’s bullet as he fought in the parched grasslands of South Africa during the Boer War.

As a young army officer he was on patrol with his men when they were surrounded by a vastly superior enemy force. Despite that, he brought them to safety in what was called at the time ‘an act of conspicuous gallantry’. Had he died that day he might have gone down in history for another memorable phrase, uttered when called on to lay down his arms: “We came here to fight, not to surrender.”

Oates was born in Putney in 1880. His family were wealthy landed gentry and in 1891 his father moved the family to Gestingthorpe where he became Lord of the Manor. The family had a connection with the area stretching back centuries: an ‘Otes’ held the Manor of Gestingthorpe at the time of the Domesday Book and the name Otes appears among those who fought at the Battle of Hastings. In 1270 Hugh Le Fitz Oates accompanied Edward I on a crusade to the Holy Land.

Lawrence Oates attended Eton but left after two years because of ill health. It was around this time his father died and at the age of 16 he found himself technically master of his mother’s house and Lord of the Manor. However, the real power lay with his formidable mother, Caroline, who remained at Gestingthorpe Hall until her death in 1937.

Education was a challenge for the young Oates. He had hoped to go to Oxford as route to the army but the entrance exam was beyond him. So instead he attended a so-called educational ‘crammer’ on the south coast to study for the ‘PS’ exam. This was roughly equivalent to O levels. The Boer war broke out in October 1899 and entry to the army as an officer became easier. In January 1900 Oates managed to get himself a commission which he took up in April at the age of 20.

The British Army at this time was slowly beginning to modernise but bravery was still more highly valued than strategic ability. Officers were expected to remain cool under fire when bullets whistled past or shells exploded nearby. Many senior officers believed the idea of taking cover bordered on cowardice. Training for all ranks left much to be desired. Army teams competing in a shooting competition around this time fired 1100 rounds only five of which hit the target.

In January 1901 the Boer War had been going on for more than a year and Oates found himself sailing into Cape Town aboard a troop ship having been posted to the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons. On arrival he was immediately sent into action.

Despite being 6000 miles from home, the English social hierarchy remained firmly in place and although a most junior officer Oates was assigned two private soldiers as servants. He wrote home saying one of them was excellent, good with the horses and did the work of six men. The other he dismissed as being ‘too fat and soft to do well here’.

Oates loved the physical challenges of the army life as he rode through the Cape Colony in search of the Boers. In another letter home he apologised for state of the paper on which it was written: ‘Excuse this dirty paper but water is very scarce and I have not had a proper wash for two days.’

A couple of months after arriving in South Africa, Oates was sent out to lead one of three patrols near the town of Aberdeen looking for Boers who had abandoned the settlement after a short skirmish.

The patrols each consisted of 15 men – a size which had two disadvantages: They were too small to put up a successful fight and too big to escape detection by the enemy. Of the three patrols, one was captured, one was pursued back to Aberdeen by the Boers and that led by Oates found itself surrounded and facing overwhelming odds.

At 7.30 in the morning his patrol had been out for two hours when it suddenly came under a hail of rifle fire from a hilltop. Four men were wounded and Oates ordered the patrol back to a dry river bed with the injured, leaving three men to cover their retreat. One of the three failed to return having been captured.

An exchange of fire with enemy lasted for hours and as each man ran out of ammunition Oates sent him back to town. Eventually the men found themselves surrounded with no hope of escape. At this point the Boers sent the soldier they had captured earlier with a message demanding their surrender. Oates declined and refused to send back the messenger. After more fighting a Boer appeared with a white flag and a written message again demanding surrender. In reply to this Oates despatched the terse message: ‘We came here to fight, not to surrender.’

Shooting began again but around midday the Boers began to disperse. However, one of their parting shots hit Oates in the thigh, shattering the bone. He ordered the remaining uninjured men back to town and settled down to await rescue with two wounded soldiers. They remained without water under the hot South African sun for six hours before help arrived. Among the rescuers was a doctor who set Oates’ thigh bone using an improvised splint made from parts of a packing case. He then had to endure a six-mile journey to safety without any form of anaesthetic.

Oates was mentioned in dispatches and recommended for the Victoria Cross. However the medal failed to materialise, much to the disgust of his regiment.

It took months for Oates to recover and he was left with one leg shorter than the other and a limp. Many believe this injury ultimately led to his death in Antarctica where the intense cold aggravated the wound and he struggled to keep up with his companions. One officer who served with him in South Africa wrote:’ It was (there) he received his death blow, as he was never physically quite the same again’.

In June 1901, still recovering from his injury, Oates arrived home in Gestingthorpe to a hero’s welcome. His mother arranged a lavish celebration: the children of the village were invited for tea in the garden at 3 o’clock and everyone else for dinner at four. The children enjoyed cake, bread and butter and jam. Two hundred and eighty-one adults sat down in the barn to beef, mutton, hot plum pudding and brown ale.

After dinner Oates was presented with an address from the village which read: ‘every Englishman’s heart must have thrilled with emotion when he read the account of your conspicuous valour’. It concluded with the hope that he would soon be restored to health and strength and able to re-join his regiment.

In reply Oates said that whatever the Boer war had cost in lives and money, was more than recompensed by the tremendous affection shown by the colonies for the mother country. He ended by thanking the villagers for the honour they shown him in presenting the address which he would always keep as one of his greatest treasures.

With that everyone adjourned to a nearby field where a fairground had been set up which included swings and a steam roundabout.

Oates continued to convalesce at home but by the end of 1901 he was well enough to re-join his regiment. He spent almost a decade serving in Ireland, Egypt and India.

This was largely a time of peace and it may be that Oates craved the adventure he had found in South Africa. One of his army colleagues also believed that he didn’t think he was doing enough for his country.

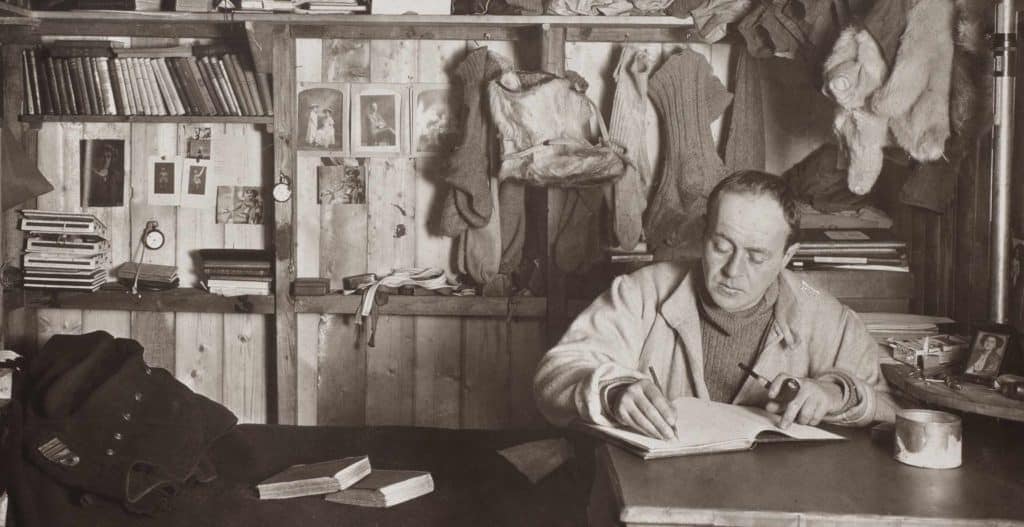

Whatever the reason, while serving in India Oates made the fateful decision to join Scott on his doomed expedition to the South Pole.

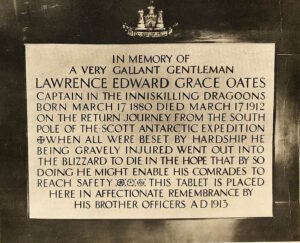

The news of her son’s death plunged Caroline Oates into deep mourning. In 1913 his fellow officers presented a brass memorial plaque to Gestingthorpe Church. It was unveiled by Major General Edmund Allenby who, during the First World War, was to lead British Forces in the Middle East.

Every week Caroline Oates would go to the church to clean the plaque. She died in 1937 and towards the end of her life it was almost the only time she left her home.

David Dunford attended the University of Essex, graduating with a degree in Government. He joined Essex County Newspapers in Colchester as a reporter and later became an assistant editor. He later moved to the BBC in London where he wrote and edited news bulletins for all BBC Radio outlets. He later became Editor of the BBC General News Service, responsible for providing news and current affairs for stations around the country. In 2003 he was Editor of all BBC local radio and regional television coverage of the second Gulf War.

After taking early retirement he became a visiting lecturer in radio journalism at the University of the Arts in London.

In 2014 he returned to Essex University to study for an MA in History which he was awarded with distinction. He has written books on the history of horse racing in Chelmsford and on the visits of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show to Essex in the early 1900s as well as numerous newspaper and magazine articles.

Images courtesy of Gestingthorpe History Group.

Published 29th January 2024