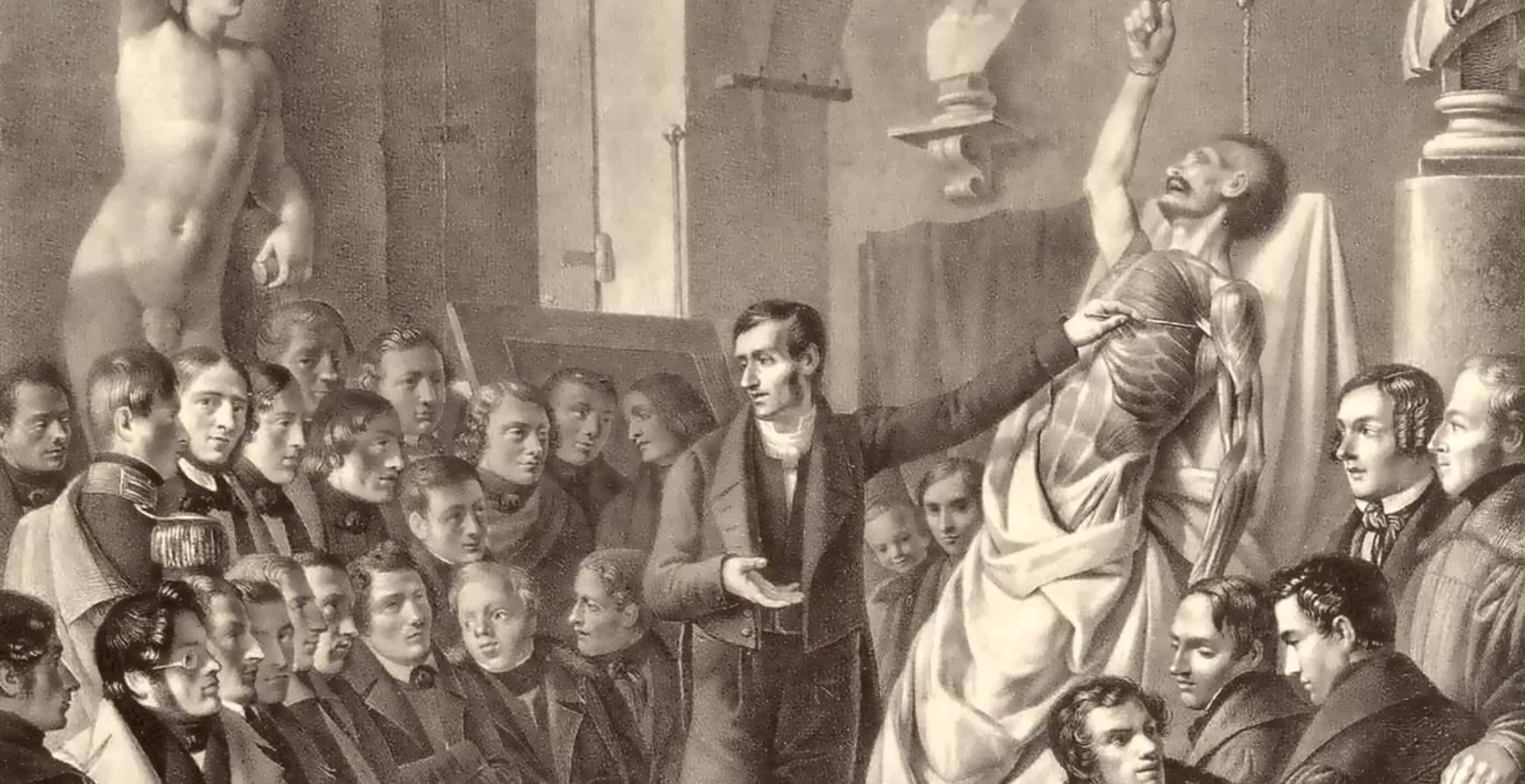

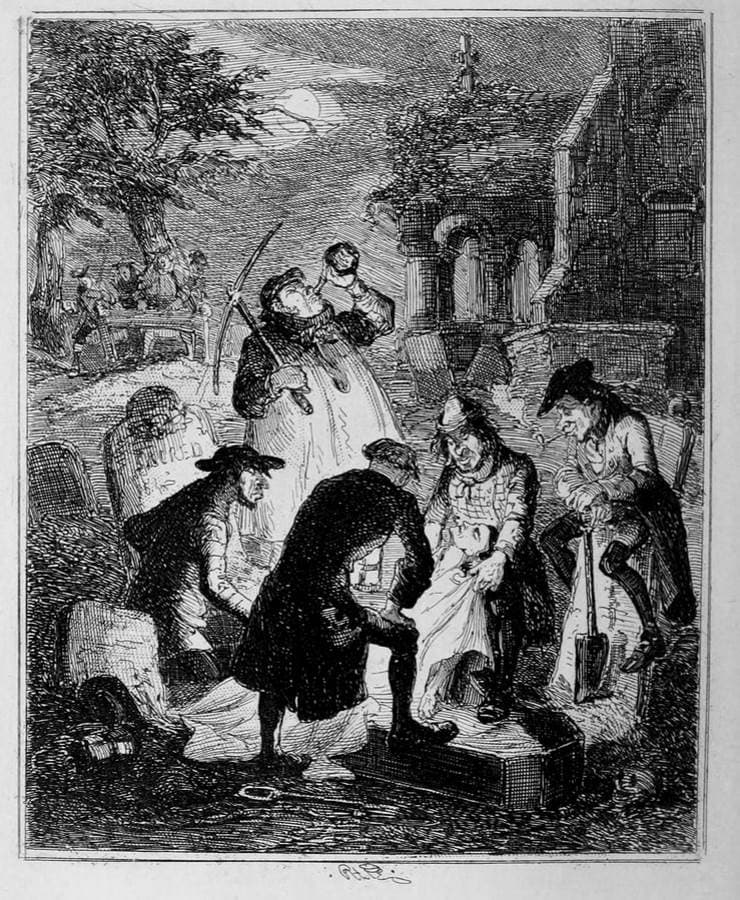

The Body Snatcher, one of the most unsettling works of Robert Louis Stevenson, describes a terrifying midnight journey in a horse-drawn gig. The three occupants are two Resurrection Men, the ghoulish haunters of graveyards in search of fresh corpses to provide to medical schools, and a body quickly exhumed and placed hastily in a sack, now seated between the two of them. As well as being Resurrection Men, the two living occupants are a doctor and a medical student, and their errand to provide a corpse for dissecting will haunt them for the rest of their lives.

For sheer horror Stevenson’s story is hard to beat: “Still their unnatural burden bumped from side to side; and now the head would be laid, as if in confidence, upon their shoulders, and now the drenching sack-cloth would flap icily about their faces. A creeping chill began to possess the soul of Fettes. He peered at the bundle, and it seemed somehow larger than at first.”

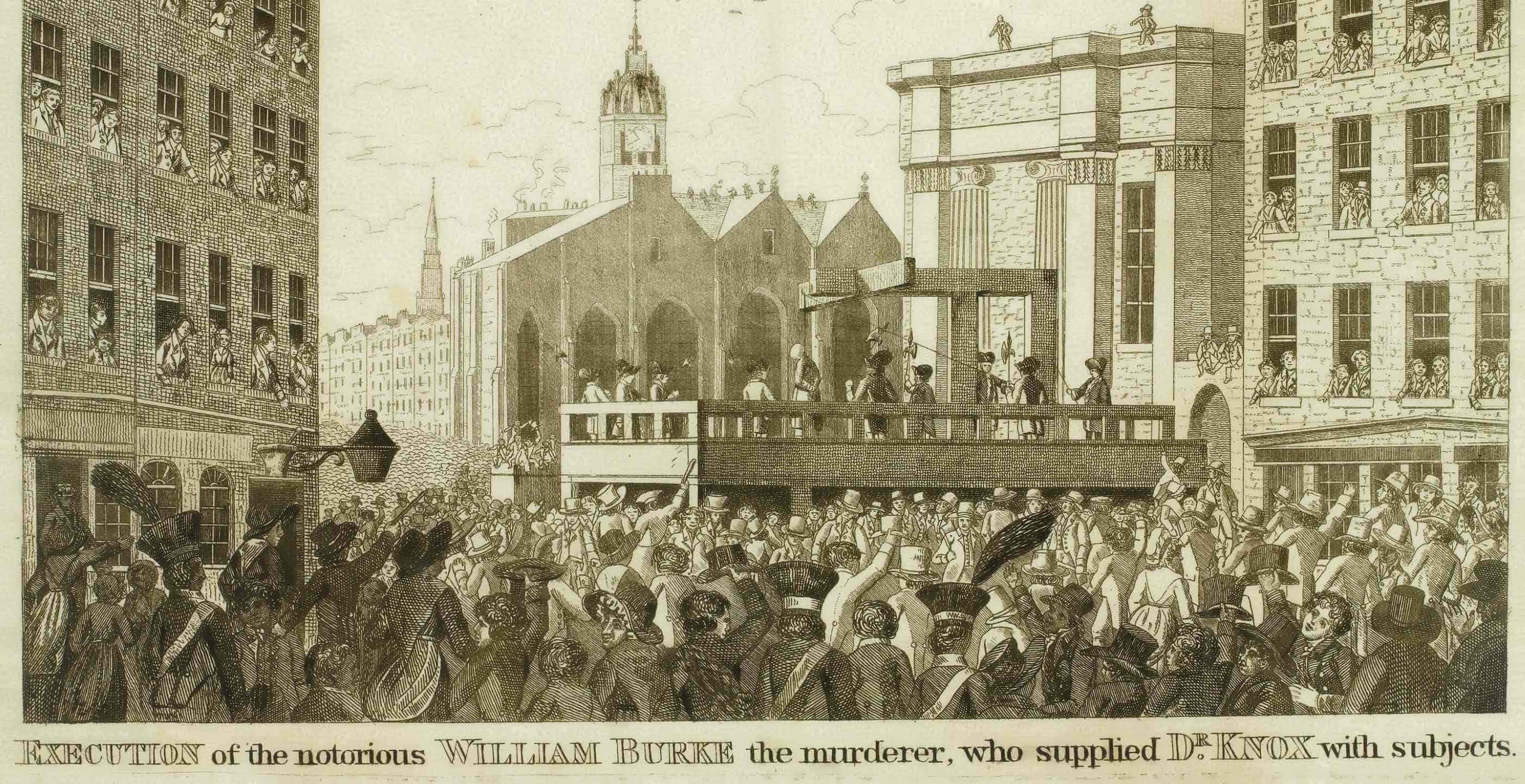

The story reflects a genuine fear lurking in the Victorian psyche: that of being removed from their coffins in the dead of night to be used as dissection specimens for medical students. The silhouettes of Resurrection Men William Burke and William Hare digging into graveyard clay by lantern light cast a long shadow over the century.

Along with being buried alive, the desecration of one’s final resting place and treatment as nothing more than a specimen was viewed with revulsion. There was also that strange fascination with the macabre that led to so much magnificent fiction of the nineteenth century. Stevenson was a major contributor to the Victorian Gothic genre with stories such as The Body Snatcher and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

As gloomy and impressive Victorian graveyards grew along with the increasing population, the public was ready for the supernatural. As early as 1762, the Cock Lane Ghost ushered in a new media fascination with ghosts and poltergeists. During Victoria’s reign, there were numerous ghost and revenant scares, from the Hammersmith ghost of 1803 to the Norwich tower ghost of 1845. These were often sparked by the discovery of a real body. And where the spooks and ghouls were, so too were the crowds and the press.

The now legendary fear of the Resurrection Men led to a major riot in Sheffield in 1862. The focus was Wardsend Cemetery, an overspill burial ground that opened in 1857. The riot began, as so many riots do, with a personal disagreement, in this case between a labourer, Robert Dixon, and the sexton of the cemetery, Isaac Howard. Robert Dixon and his wife Bethia were living in the lodge at Wardsend Cemetery, and had already made some bizarre and disturbing discoveries before the dispute between Dixon and Howard.

To begin with there was the appalling smell in the room above the stables belonging to the lodge. The Dixons had access to the room, but the stables were locked and inaccessible to them. Curiosity overcame Dixon. When he managed to peer into the stable by pushing in some knots in the wooden boards of the room above, he could make out a number of small coffins, mostly the size that would contain young children or stillborn babies, and some larger ones that might have been made for young people in their teens. There were also broken parts of coffins piled up in the stable.

Over the next few weeks, Dixon managed to discover that some the coffins were occupied, and that the sexton appeared to be removing bodies from them and stealing them away secretly. In details later recounted to court proceedings, he noted on one occasion that Howard appeared to be cutting off the leg of one child with a carving knife. His suspicions that the exhumation of recently buried bodies had something to do with providing specimens for dissecting seemed to be proven by the discovery of a pit or hole in the ground with the remains of coffins in it.

Dixon had also witnessed Howard moving the coffins to the pit. The strange thing is that for some time Dixon did not tell anyone, and when he finally did, he confided in his employer Mr Oxspring, who was also a friend of Isaac Howard. As proof of what he had been witnessing, he gave Oxspring a number of coffin plates discovered in the stable. Oxspring advised him to go to the police. Soon Inspector Crofts, of the West Riding Constabulary, and Mr Jackson, Chief Constable, were aware that something dreadful was going on.

The old saying goes that Rumour has gone half-way round the world before Truth has got its boots on. Rumours seem to have hit the Sheffield streets soon after Dixon giving a statement to the police on 31st May 1862. According to local historians and authors Chris Hobbs and Mick Drewry, the first press report appeared six days later, indicating that it was believed the bodies were being exhumed for dissection purposes. By this time, the riot had already happened and Truth was wearily panting along behind Rumour with some news that was almost as disturbing as the tale about Resurrection Men.

Inevitably with such a sensational story, it wasn’t long before crowds gathered at the cemetery to see for themselves. After all, many of them had relatives buried there. In the pit containing the coffins they also found the remains of a dissected body, which confirmed the rumours in the eyes of a crowd already primed for retribution. The subsequent riot was described in detail in local publications: “The mob forcibly entered” the sexton’s house, which was also used by the local clergyman the Reverend John Livesey, “demolished the furniture, windows, doors, &c.” before heading off to Isaac Howard’s new house. When they found out he wasn’t there – he’d already got wind of what was happening, and had fled – they set it alight and the building was totally destroyed.

The truth about what Howard was doing (and the Rev Livesey was aware of – he had purchased the land as a burial site in the first place) was to modern eyes, just as unnerving as being a Resurrection Man. The bodies were being removed from their graves without good reason and some relocated in the pit in the remote part of the cemetery that had apparently been dug for that purpose. It was a fairly standard occurrence in many cemeteries that older burials would be disinterred and removed to charnel houses, or simply lost, in order to create new space. However, that doesn’t seem to have been the reason in this relatively new burial ground. The remains of the dissected body were those of Joseph Gretorex, a vagrant, which had been obtained perfectly legally by the medical school. Nonetheless, the subsequent treatment of the remains of his body strikes a deeply unsavoury note.

Livesey and Howard were tried at the York Assizes on the 24th of July. The Reverend was accused and found guilty of making a false entry of burial and for giving a false certificate and received nominal punishment of imprisonment for three weeks. Howard, accused of disinterring bodies, received three months in prison, and later claimed some money back for the destruction of his house and belongings, though not receiving its full value.

What is perhaps the saddest part of this strange tale are the testaments of the people whose small children had died and who were caught up in the whole bizarre episode. Harriet Shearman, for instance, who found one of the coffins in the pit contained one of her children. She added “We have another child there, or it should be there… We have not looked for the coffin of the first child.” If nothing else, Livesey and Howard should have felt some shame at the creation of such distress.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 14th June 2024