Many people remember that surreal moment during the London 2012 Olympics when H.M. Queen Elizabeth II appeared to descend into the Docklands Olympic Stadium from a helicopter, accompanied by James Bond. The Crown’s smoothest and most sophisticated spy was played by the admirably cool actor Daniel Craig, who managed to control any urge to squeal “OMG I’m parachuting with The Queen into the Olympic Stadium! MEGA-EPIC or WHAT!”

That’s because he wasn’t really, of course. It was a beautifully stage-managed sequence, during which a not shaken or stirred Craig apparently turned up at the Palace to escort Her Majesty to the opening ceremony of the London Olympics on an official flight. And for one jaw-dropping instant, the watching world believed that the Queen really had dropped in on a parachute.

The opening ceremony of the Games continued in fantastic style. Britain’s industrial past was celebrated by top-hatted entrepreneurs, led by actor Kenneth Branagh, directing the productive proletariat as they forged five Olympic rings. Nurses danced and patients bounced on giant beds in recognition of the establishment of the UK’s National Health Service in 1948, which was also the year in which Britain had last hosted an Olympic event.

In comparison to 2012, that first post-war Summer Olympics in London was a low-key affair. Unsurprisingly after six years of global conflict, the country was still struggling with shortages and the restoration of some kind of economic stability. The 1948 London Olympic Games, also known by their official title of the Games of the XIV Olympiad, as well as London 1948 or the 1948 Summer Olympics, became known as the “Austerity Olympics” with a certain pride. No one tried to hide the fact the games would be delivered on a shoe-string budget. In fact, everyone knew it was going to be pants, and embraced it enthusiastically.

Underpants, that is. Drawers. Briefs, trunks, or y-fronts. Shorts, knickers, or bloomers. Undies. Boxers. The unmentionables.

No shorts please, we’re British was the order of the day, and don’t you know there’s just been a war on? All participating British athletes had to provide their own shorts, whether bought (posh!) or home-made (pass me that redundant parachute silk!). However, a local retailer, spotting a sponsorship opportunity, gave every male athlete a free pair of underpants. Mutterings of “Well, that’s the patriarchy for you” and “we fought the war too, you know” from the women’s quarters, and possibly the start of the post-war feminist movement in Britain.

“We’ll provide you with bed linen,” sniffed the organisers, “but you’ll have to provide your own towels. Or – “ (spotting a fund-raising opportunity) “you can hire them – from us!”

It’s a world away now, and hard to imagine Sir Andy Murray, Dame Fatima Whitbread, or Sir Mo Farah being greeted by “Apologies, but all we have are medals made out of milk bottle tops and some very practical garments for your nether regions. Well done!” Having said that, anyone who has some genuine experience of austerity will recognise the true value of those most despised and unimaginative of gifts: socks and underwear. What’s more, the 1948 medals were made by a local London firm, and were silver gilt (rather than gold), silver, and bronze. Milk bottle tops were just too important to the economy to be used for anything as frivolous as medals.

No new stadia were constructed in 1948, but it was not as though Britain did not have some fine sporting venues. The main one, known at the time as the Empire Stadium, was at Wembley, and hosted the athletics events. The aquatic events were held at the Empire Pool, which also served as a boxing venue (with the pool boarded over of course!). There was sailing at Torbay, rowing at up-market Henley, and shooting at Bisley. The equestrian events were held at Aldershot, apart from the team show jumping, which was at the Empire Stadium.

Beyond the Olympics, Wembley mainly hosted speedway and greyhound racing events. Now faced with the prospect of welcoming track and field athletics, a cinder track was installed. Despite opposition from the regulars, how good it looked in the extremely dry period that led up to the Games. Then the heavens opened, as is the way in Britain, and the athletes found themselves running through a sticky, gritty bog. The cyclists at the Herne Hill velodrome didn’t fare much better, with the pre-deluge heat melting the bitumen of the track.

The international athletes were housed in former army and RAF camps, the main one being at Richmond Hill. The sites received an upgrade but couldn’t compare with the purpose-built Olympic Villages of pre-war Olympic Games. However, housing athletes in upmarket temporary villages while many people were desperate for housing in bombed-out Britain would have been the height of insensitivity.

Women athletes had to be housed separately from the men (no sharing those hired towels please, we’re British!). Some office blocks were temporarily converted to accommodation. The British women’s swimming team found themselves eight floors up and the lift wasn’t working. Several women athletes recall being housed over Victoria Coach Station in London, in a notorious red light district. This led to some difficult encounters as the young women, many with only a basic knowledge of English, made their way to and from their sporting events.

To add insult to injury, the phenomenally successful Dutch athlete Fanny Blankers-Koen was known to the press as “the flying housewife”. Mutterings of “well, that’s the patriarchy for you” and “has the feminist revolution started yet?” from Victoria Coach station. However, any complaints about the menfolk were drowned out in a general cry from all athletes of “I’m starving, have those food parcels from Australia arrived?”

For food was certainly an issue at the Austerity Olympics. Rationing was still in place in Britain, and the organisers of the Games, with an eye to the cost, were disputing among themselves as to exactly how many calories an athlete really needed to turn in their best performance. Forget illicit drugs; had that runner sneakily obtained an additional boiled egg or not? Chickens were interrogated under bright lamps until they cracked to find out if they’d been providing foreign teams with additional eggy input.

“2,600 calories per day should suffice,” ordered the bureaucrats, as tea ladies delivered cuppas and biscuits to their desks. “You cannot be serious,” responded the athletes, returning from yet another sweaty three-hour training session on the melted bitumen track in their home-made shorts. Eventually the daily allowance was raised to over 5,400 calories, which matched that of heavy industry workers such as miners and dockers. (A good insight into how much food real welders would have needed if forging massive Olympic Rings like those of the 2012 Opening Ceremony.) Fortunately, the meagre rations were augmented by food parcels from around the globe.

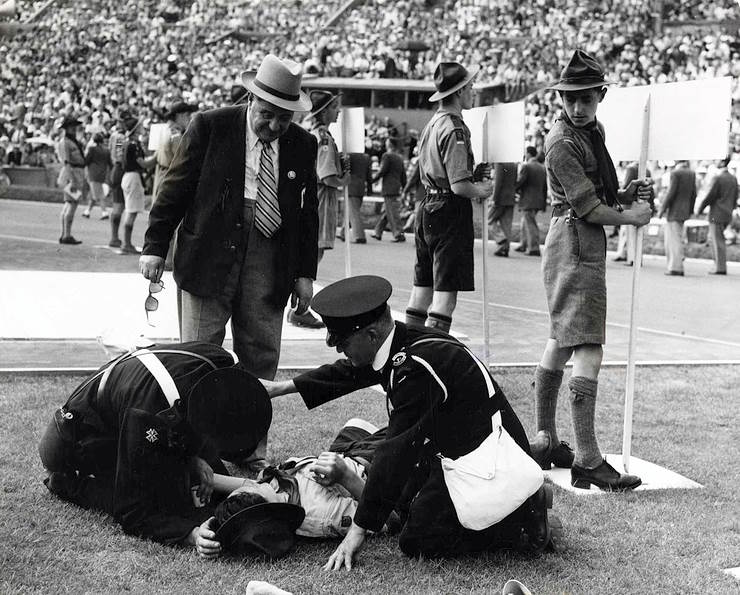

The games opened on Thursday 29 July 1948 at 4 pm, in boiling hot weather, at the Empire Arena in Wembley. The royal family had arrived earlier so that the King could officially open the Games. The teams, most of which had been perspiring strongly in the heat, and some near fainting, marched in, each preceded by a Boy Scout doing his duty to God and the King. The Olympic torch was carried by John Mark, who crunched over the mercifully still dry cinder track to light the Olympic cauldron atop a flight of steps. Mark, a student at Cambridge, was a successful track and field athlete.

Things didn’t quite go according to plan, though. The idea had been to release a massive flock of pigeons over the arena, cued by a volley of cannon. The cannons got stuck in a traffic jam, and some of the pigeons, which had been there for some time, had succumbed to the heat. Many of the unfortunate birds died. (Given the food shortages, perhaps it is to be thankful they weren’t turned into pies – or, were they?)

As the games commenced, it was all terribly austere too, and the lighting was a far cry from the spotlights and the glitzy red, white, and blue of the London 2012 Olympics. However, when life gives you lemons, make lemonade, and in the dark if necessary. At times the arena had to be lit by car headlamps, and the javelin event turned out to be particularly challenging. Nonetheless the plucky contestants took aim as best they could and gave it their best shot, watching the torchlight bobbing across the field as officials ran to measure their throws. As long as they weren’t greeted by “Arrrrghhhh!” at the end of each throw they knew they were in with a chance.

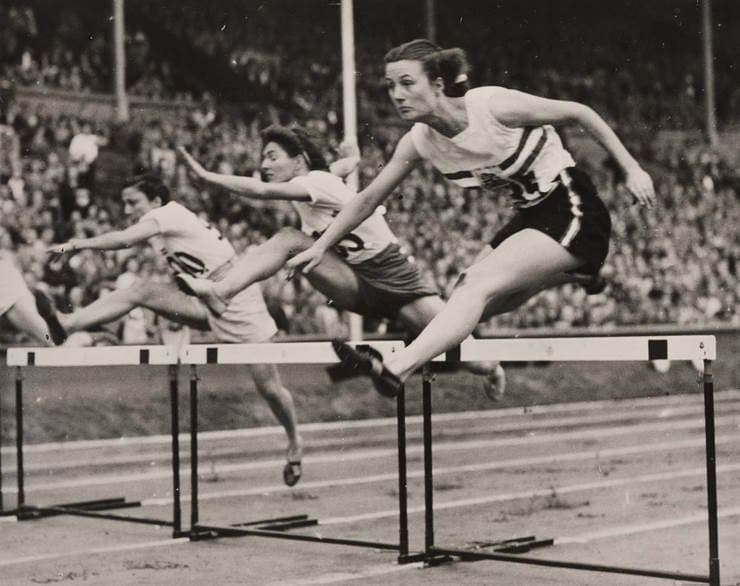

Despite differentials between the 3,714 men and 390 women athletes who took part in the Games, London 1948 struck equality gold with some notable firsts. Blankers-Koen took four gold medals, winning the 100 metres, 200 metres, 80 metre high hurdles, and being a member of the winning 4 x 100 metre relay. (Cries of yards please, we’re British and we haven’t had decimalisation yet! from the bureaucrats.)

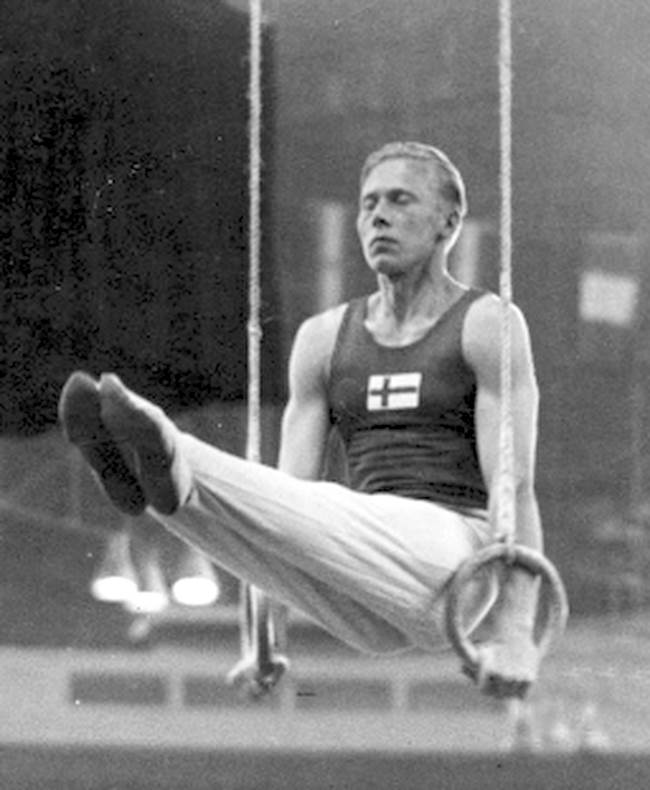

Despite already holding long jump and high jump world records, Blankers-Koen was disbarred from taking part in any further events due to women athletes only being allowed to participate in three individual events. (Did the officials believe it risked interfering with their housewifeing?) No such restrictions on Finland’s Veikko Huhtanen, who won a remarkable three golds, a silver and a bronze in the men’s gymnastics section.

Arthur Wint took gold in the men’s 400 metres, being the first Jamaican to win an Olympic gold medal. In the 800 metres, he took silver. Audrey Patterson was the first African-American woman to win an Olympic medal, taking bronze in track and field. Subsequently her colleague Alice Coachman became the first African-American woman to win an Olympic gold medal in track and field, and the sole American woman to do so in athletics that year.

Not that the Games were an entirely global meeting. Neither Germany nor Japan was invited. Italy sent a team, as they had signed a peace treaty with the Allies. There was no team from the Soviet Union, which had lost 40 million people in the war against fascism, although they were invited. There was no Israeli team, as the state of Israel had not been recognised by the International Olympic Committee at that time.

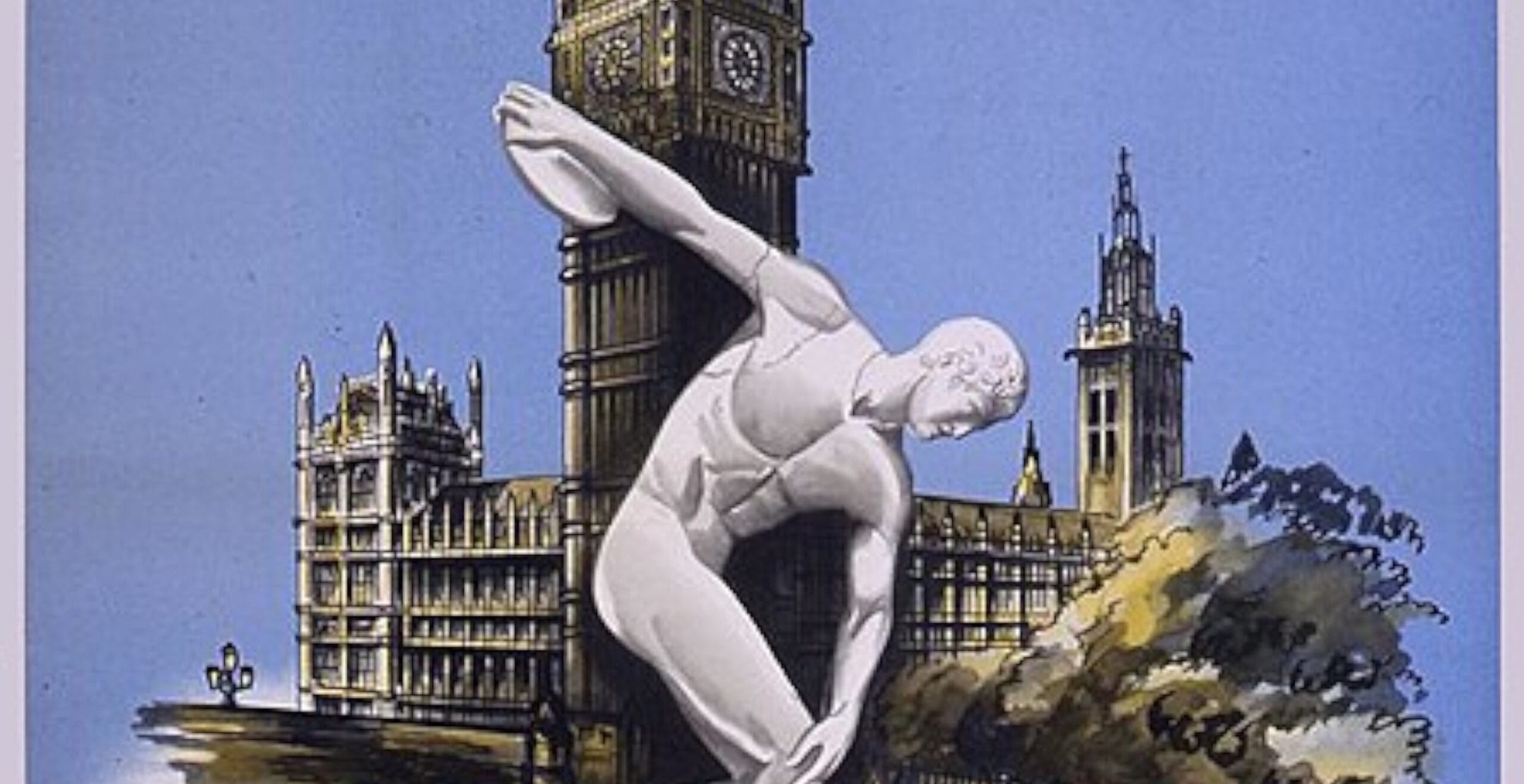

Away from the sticky cinder track and its Olympian battles, a more relaxed type of activity was taking place under the aegis of the Games. London 1948 was the final year in which art competitions would be held as part of the Olympics. Yes, once upon a time, Olympic medals were awarded in architecture, literature, music, sculpture, and painting. And the Brits did not too badly, which some might think is a good reason to bring them back.

No ageism here, either. In the “etching” sub-section, 73-year-old John Copley took silver with his “Polo Players”. The gold medal winner’s subject was “Swimming Pool”. “Seaside Sports”, “Meath Hunt Point-to-Point Races”, cycling and hockey provided other sporting themes. Nor was the arts section an easy option. No medals were awarded for drama, and a further five subcategories of the event received no gold medals whatsoever. There were no reports of cheating, although the desire to spill paint brush water over a rival entry must have been strong.

When the games ended on Saturday 14 August, and the towels were handed back in, the Austerity Games that had cost an estimated £732,000 produced a pre-tax profit of around £29,420. More importantly, they would be remembered for their fun, camaraderie, and sense of achievement, as well as sticky tracks, rationed eggs, underpants, and javelins in the dark. Not to mention being a spectacular success for BBC Television (at least for London viewers), which would lead to a thirst for televised sports across the nation as post-war homes began their love affair with the gogglebox.

1948 was an immensely important year in both British and Irish history. The National Health Service became fully operative. It was an important component of the post-war Labour Government’s vision of the Welfare State, with its message of “universality” of treatment and support. A new type of school, the Comprehensive, and a new type of school examination and certification, the GCE (General Certificate of Education) were being established. Railways and the UK’s electricity supply were nationalised. The second vote that had been available to some businessmen (most being men at that time) and students was abolished. Éamon de Valera’s party lost power in Ireland, and Ireland subsequently left the Commonwealth. Britain signed a treaty with France and the Benelux countries that would eventually lead to the creation of NATO.

The 1948 Olympics were the first games to be held since the infamous Berlin Olympics in 1936 under the Nazi regime. After the excesses of the ceremonies of that year, the Austerity Olympics were a fresh start. The 1948 Games reminded the world that the hardships of war, still so vivid in people’s memories, were now over, and looked forward with hope to a future of peace, sporting achievements, and friendship between athletes from all over the globe. Not to mention fresh underwear for all!

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 6th October 2023.