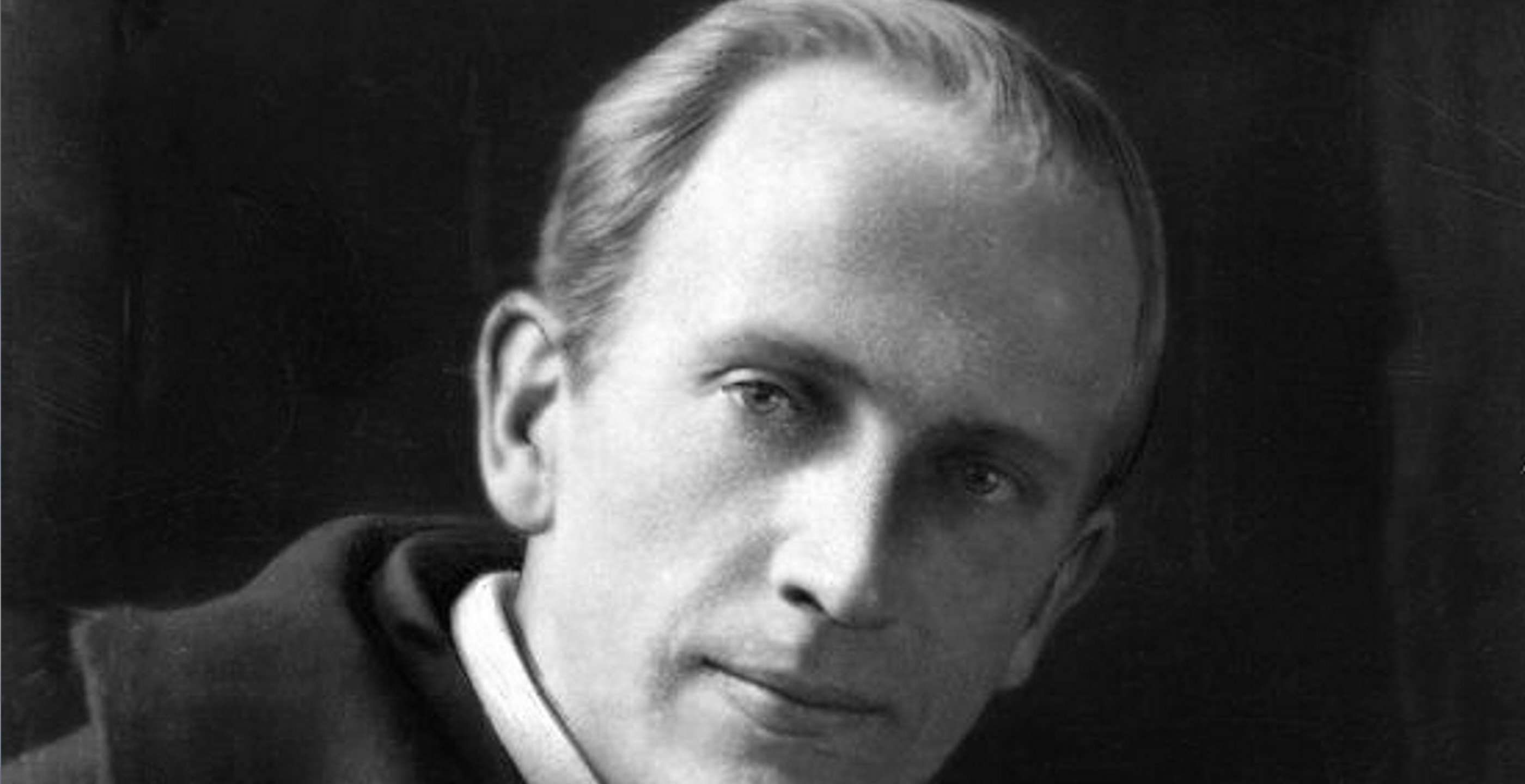

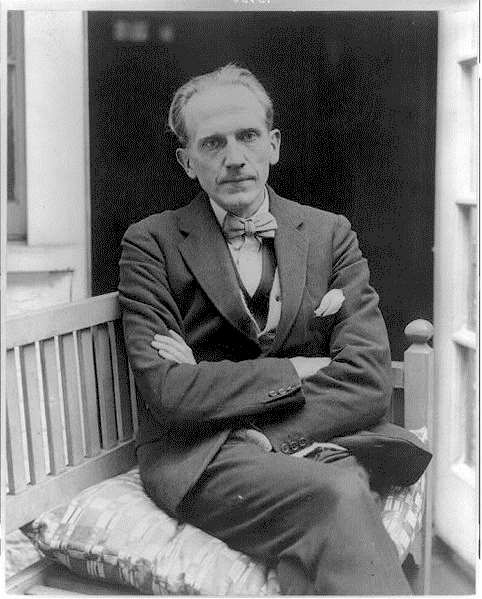

The majority of people today will know Alan Alexander (A. A.) Milne best as the author of the Winnie-the-Pooh books. The honey-loving bear of very little brain and his toy animal companions Piglet, Owl, Eeyore, Tigger and friends were all brought to life in stories written by Milne to entertain his young son Christopher Robin.

Since his first appearance in 1926, Winnie-the-Pooh has become an international superstar and brand, thanks largely to the Disney Studios’ cartoon version of his stories. This means that Milne is an author whose reputation has been caught up in the success of his own creation and eventually overshadowed by it. He’s not alone in that, of course.

Original Harrods toys purchased for Christopher Milne in the early 1920s. Clockwise from bottom left: Tigger, Kanga, Edward Bear (a.k.a Winnie-the-Pooh), Eeyore, and Piglet.

Original Harrods toys purchased for Christopher Milne in the early 1920s. Clockwise from bottom left: Tigger, Kanga, Edward Bear (a.k.a Winnie-the-Pooh), Eeyore, and Piglet.

In the early 1920s though, A. A. Milne was best known as a playwright and essayist, and also as a former assistant editor of Punch, the UK magazine that became a national institution through its humour, cartoons and commentary. He was just 24 years old when he took on the job in 1906.

Some of the pieces he wrote for Punch were loosely based on his own life, often disguised through fictional characters and settings. They are characterised by gentle, wry humour and an unmistakeably British ambiance in which he gently pokes fun at trips to the seaside, days in the garden, games of cricket and dinner parties.

His work was popular. His collection of essays “The Sunny Side” went through 12 editions between 1921 and 1931. Occasionally, though, a darker edge shows through the light-hearted and quizzical tales of life in the Home Counties.

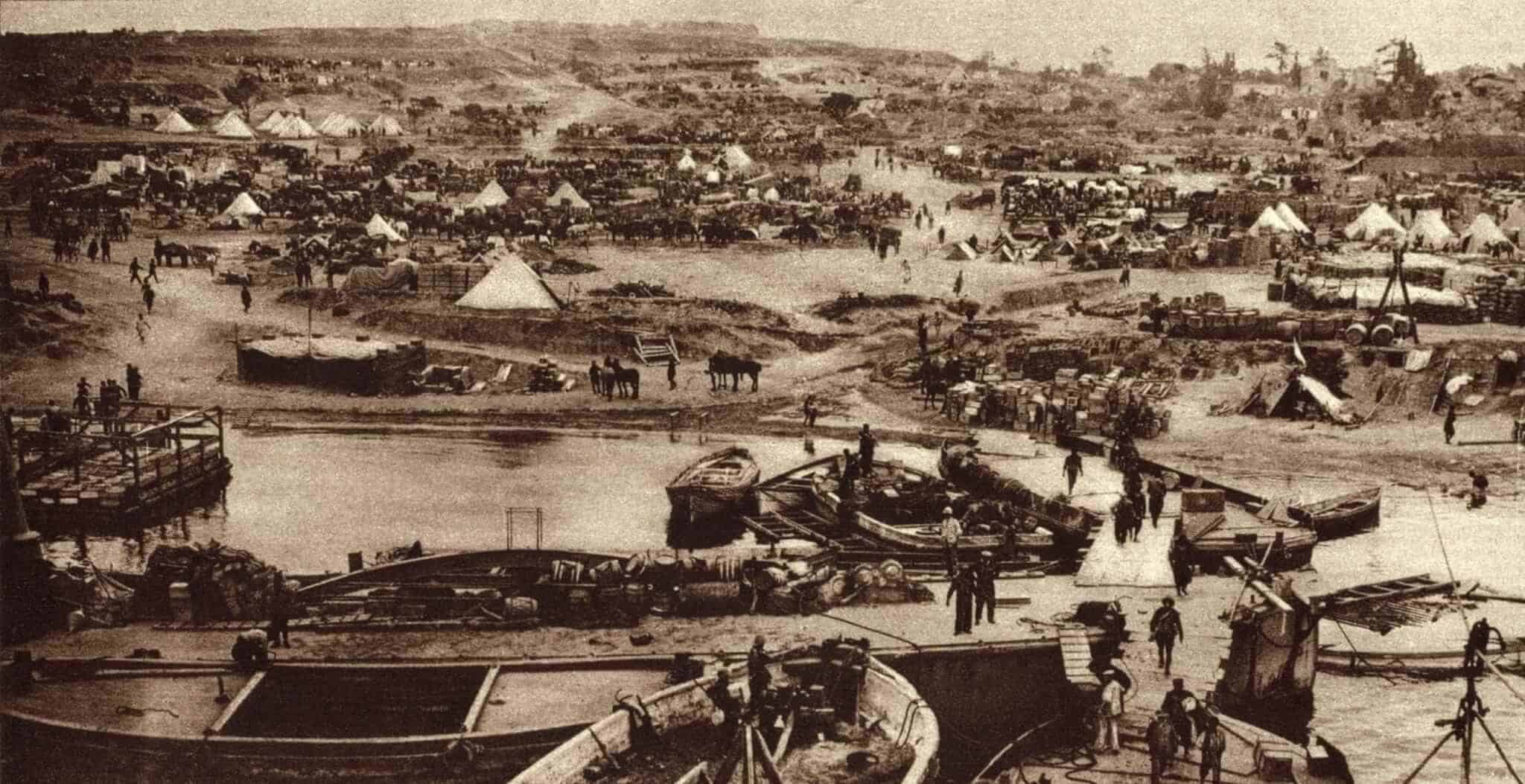

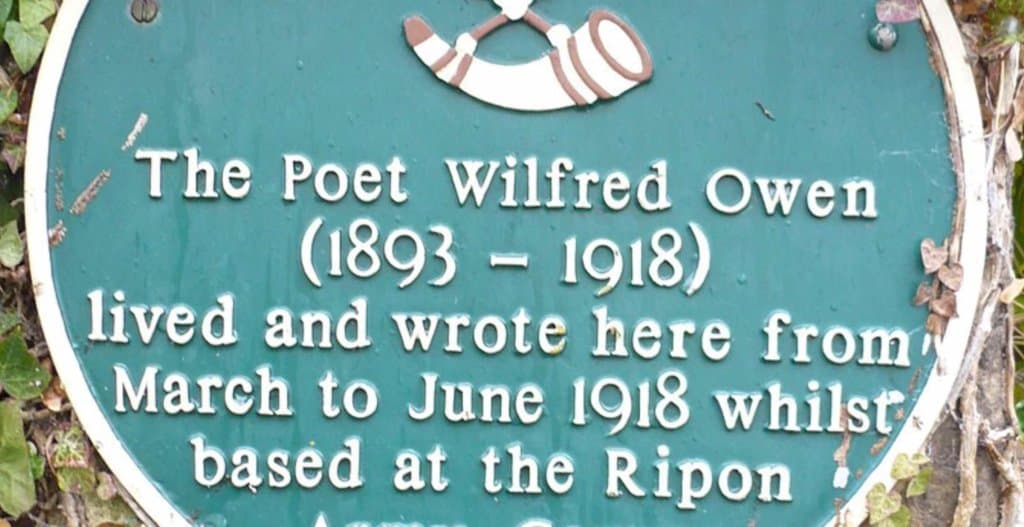

Milne was a Signals Officer during WWI and witnessed at first hand the destruction that wiped out a generation of young writers and poets. His own work on the subject of the war did not have the horror of Wilfrid Owen’s poems or the biting irony of those of Siegfried Sassoon. However, his simple tales of greed and entrenched bureaucratic stupidity still have impact today as shown in his poem “O.B.E.”:

I know a Captain of Industry,

Who made big bombs for the R.F.C.,

And collared a lot of £.s.d.-

And he – thank God! – has the O.B.E.

I know a Lady of Pedigree,

Who asked some soldiers out to tea,

And said “Dear me!” and “Yes, I see” –

And she – thank God! – has the O.B.E.

I know a fellow of twenty-three,

Who got a job with a fat M.P.-

Not caring much for the Infantry)

And he – thank God! – has the O.B.E.

I had a friend; a friend, and he

Just held the line for you and me,

And kept the Germans from the sea,

And died – without the O.B.E.

Thank God!

He died without the O.B.E.

In one of his prose pieces Milne jokingly takes on the arrival (or non-arrival) of the second star that will mark his promotion from Second Lieutenant to Lieutenant:

“Promotion in our regiment was difficult. After giving the matter every consideration, I came to the conclusion that the only way to win my second star was to save the Colonel’s life. I used to follow him about affectionately in the hope that he would fall into the sea. He was big strong man and a powerful swimmer, but once in the water it would not be difficult to cling round his neck and give an impression that I was rescuing him. However, he refused to fall in.”

In another piece, “The Joke: A Tragedy” he turns the horror of living in trenches alongside rats, into a shaggy dog story about the issues of being published with misprints. One tale deals lightly with the issues of betrayal by a fellow officer who is a love rival to the hero of the story. “Armageddon” picks apart the meaningless of conflict by crediting it all to the desire of a privileged, whisky and soda drinking golfer called Porkins who thinks England needs a war because “we’re flabby…We want a war to brace us up.”

“”It is well understood in Olympus,” writes Milne, “that Porkins must not be disappointed.” There then follows a Ruritanian-style fantasy of jilted captains and patriotic propaganda, all overseen and manipulated by the gods, which tips the world into war.

Milne’s poem “From a Full Heart” reveals, through its almost absurdist images, the depth of the soldier’s desire for peace after conflict:

I’m even upset by the lowing of cattle,

And the clang of the bluebells is death to my liver,

And the roar of the dandelion gives me a shiver,

And a glacier, in movement, is much too exciting,

And I’m nervous, when standing on one, of alighting -

Give me Peace; that is all, that is all that I seek…

Say, starting on Saturday week.”

This simple, surreal language expresses “shell shock” (which would now be called PTSD) so effectively. The slightest noise or unexpected movement can trigger a flashback. War destroys even our relationship with nature.

During WWII Milne became a captain in the Home Guard, despite his WWI experiences leaving him opposed to war. His friendship with P.G. Wodehouse broke down over the apolitical broadcasts Wodehouse made after being taken prisoner by the Nazis.

Milne grew to resent the fame of his stories about Pooh and his friends and returned to his favourite genre of wryly humorous writing for adults. However, the Winnie-the-Pooh stories are still the writing for which he is best known.

In 1975, the humourist Alan Coren, who had also become assistant editor of Punch in his early twenties, wrote a piece called “The Hell at Pooh Corner” shortly after the publication of Christopher Milne’s autobiography, which had revealed some of the reality about home life with the Milnes.

In Coren’s piece, a raddled, cynical Pooh bear looks back over his life and what might have been. When “interviewed” by Coren, who suggests that despite everything, life with the Milnes must have been fun, he gives an unexpected response:

“’A. A. Milne,’ Pooh interrupted, ‘was an Assistant Editor of Punch. He used to come home like Bela Lugosi. I tell you, if we wanted a laugh, we used to take a stroll round Hampstead cemetery.’”

It’s a line in a style that A. A. Milne would surely have appreciated. He was of a generation that was not used to sharing their experiences or their emotions. Humour helped them to cope.

My own copy of Milne’s “The Sunny Side” is falling apart. In the front cover, there’s an inscription from my aunt and her husband to my mother on her birthday. The date is May 22nd 1943. It’s strangely comforting to think of them being cheered up by his humour in the depths of WWII, just as my spirits lift whenever I read it.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.